The kitschy cottages on canvas are instantly recognisable, bathed in a warm light and wreathed with flowers in a nostalgic and colourful explosion of paint. Thomas Kinkade’s work was inescapable throughout the Nineties; it was nearly impossible to walk through any shopping mall — or suburban home, for that matter — without catching a glimpse of his trademark works.

The artist built an empire on his paintings, grounding his own image in faith and family — as he and the machine behind him bragged that a Kinkade hung in one in 20 American homes. By 2001, an actual California subdivision modeled in the Kinkade style emerged, with potential buyers flocking to tour cutesy homes and mock-cobblestone driveways.

“Beneath your Thomas Kinkade painting, you can put a Thomas Kinkade couch next to your Thomas Kinkade books, Thomas Kinkade throw rugs, Thomas Kinkade collectibles ... you put all of that inside your new Thomas Kinkade home in the Thomas Kinkade subdivision,” one Nineties commentator proclaimed on TV, where the artist and his brand were a constant presence, whether Kinkade himself was teaching viewers to paint or salespeople were hawking his wares on shopping networks.

But cracks eventually began to show in the Kinkade facade. As fans reflected on his distinctly serene scenes, the artist himself was weathering business woes, a marriage breakdown, addiction problems and, as chronicled in detail in a new documentary, a devastating internal struggle with his life and his work.

He was also secretly channeling those demons into a cache of dark art diametrically opposed to the images which made him famous — and his family only discovered them in his vault following his tragic 2012 death at the age of 54.

“He was this larger-than-life figure who lived sort of a Greek tragedy of a life,” Miranda Yousef, filmmaker of the new documentary Art for Everybody, tells The Independent. “And when I got into researching and I got in touch with the Kinkade family, it sort of blew my mind, the whole aspect with the vault. There was a lot of stuff that was public knowledge before — everybody knew about his painting, his ‘painter of light’ persona, and then a little bit later, towards the end of his life, they also knew about his struggles with alcoholism, and, ultimately, his tragic death.”

“But then this whole aspect of the vault was a totally different can of worms,” Ms Yousef says. “And it just broke open the story in a way that I was really excited about.”

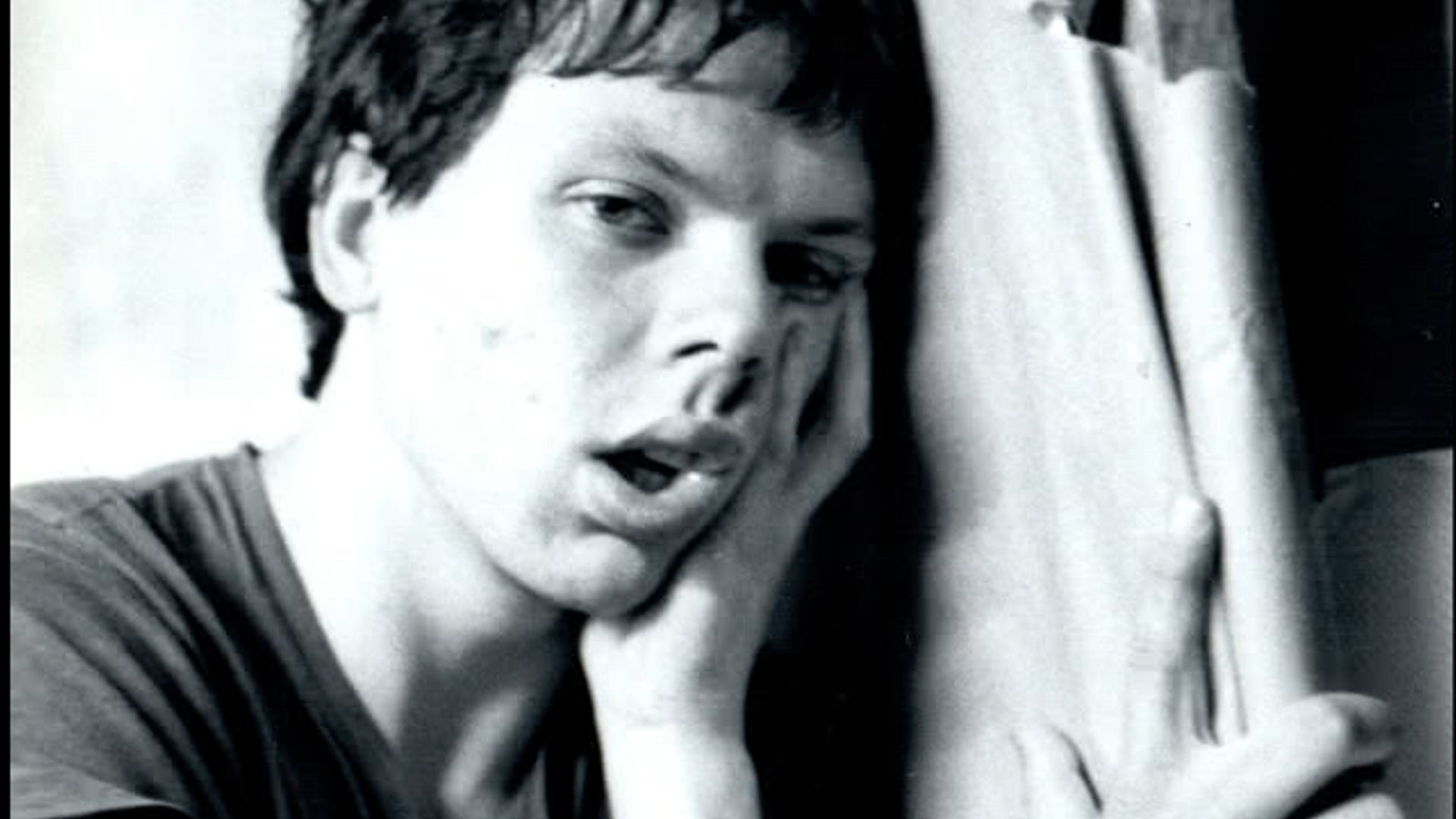

The film paints a portrait of a man torn between desire for critical acclaim and commercial success from nearly the inception of his career. He’d recorded notes for himself from a young age and, in one teenage musing included in the film, ponders his creative predicament.

“I’m 16,” he says. “I want to be an artist; I have that dream. However, I've been also realising ... I don't want to end up like Van Gogh. And yet something within me says I do want to end up like Van Gogh for the sake of achieving greatness.”

Financial stability, however, was a major driving force for Kinkade, whose parents’ divorce left him living in a ramshackle home with a single mother in Placerville, California. His brother describes how Kinkade “had a very profound feeling that having so much less than others, not having a decent house to live in and not having a father in the house, made him somehow less.”

After college, Kinkade successfully tried his hand at animation, working for Ralph Bakshi studios, but his ambitions lay beyond background movie art. An avid fan of Walt Disney, Kinkade wanted to establish his own legacy and reputation — and after his wife had luck selling prints of the local clocktower outside a Placerville store, it became clear that such a career was a realistic goal.

“From day one, he wanted to make his art more accessible to a larger population; he just had a heart for people who loved art but couldn't afford original art from a standard gallery,” Kinkade’s wife, Nanette, says in the film. “So he started to publish limited edition prints.”

A chance meeting with a future business partner at a wedding — and a plan sketched out on a napkin — helped forever change the Kinkades’ lives. The seeds of Thomas Kinkade as an enterprise had been planted, and its trajectory would prove that the painter’s art tapped into a very specific subset of the American psyche.

“People find hope and comfort in my paintings,” Kinkade told writer Susan Orlean for a 2001 New Yorker piece entitled “Art For Everybody” — the inspiration for the new documentary title. “I think showing people the ugliness of the world doesn’t help it. I think pointing the way to light is deeply contagious and satisfying.”

By 2000, the company was raking in $100m; in addition to the prints and collectibles, there were television shows, furniture lines and even a tour bus. Kinkade was front and center though all of it, forever repeating the mantra of “hope, family, faith and God.”

Critics, however, ignored him; any who deigned to acknowledge Kinkade sniffed at his work. All of that annoyed Kinkade “to no end, and he will talk your ear off ... about the ugliness ad nihilism of modern art and its irrelevance compared to the life-affirming populism of his work,” Ms Orlean wrote in the New Yorker.

She described Kinkade as possessed of “the buoyant self-assurance of someone who started poor and obscure but has always been sure he would end up rich and famous.

“He is so self-assured that he predicts it’s just a matter of time before the art world comes around to appreciating him,” Ms Orlean wrote. “In fact, he bet me a million dollars that a major museum will hold a Thomas Kinkade retrospective in his lifetime.”

California artist Jeffrey Vallance staged a gallery exhibit of Kinkade’s work, but the effort didn’t meet the writer’s standard of showing the fine art world had accepted the “Painter of Light”; the rest of Kinkade’s lifetime, it turned out, would be tragically short.

As Kinkade’s fame spiraled and the business expanded, the painter was finding it hard to cope. Previously a teetotaler, he began drinking heavily and acting out, making rash business decisions such as turning on the business partner he’d so serendipitously met at a wedding. The family staged an intervention and he went to rehab; when he got out, he almost immediately stopped for a drink, his wife said. They separated, and Kinkade’s behaviour began to deteriorate along with his physical and financial health.

“I still don't know what happened,” one of his daughters says in the film. “It seemed very correlated with the insane demands that the business put on him — but that being said, there's a lot of people that feel pressure from their jobs. So there was something else, and I don't know what it was.”

Several dealers filed suit against the company, accusing it of “cranking out a lot of merchandise that they couldn't move and forcing them to buy in wholesale — and at the same time withholding pertinent financial information that would have kept them from investing in the business,” Kim Christensen, who wrote about the actions for the Los Angeles Times, says in the film. “And the other big chunk of the litigation alleged that Kinkade had traded on his Christian faith to induce these people into going into business with him.”

The plaintiffs won and the company declared bankruptcy, and, on top of that, Kinkade was charged with DUI in 2010 as his personal behaviour spiralled out of control. He grew his hair longer, wore clunky chains and skull jewelry, and — separated from Nanette — began running through girlfriends, his family says in the film. At one point, his sister drove to his studio to find Kinkade in a bad way, the place covered in bottles. The spiral was also spilling into public; Kinkade caused scenes in Las Vegas and California, heckling Siegfried & Roy and urinating on a Disneyland character, respectively.

“He had so much brain damage from the alcohol abuse that the doctor was surprised he was functioning,” Nanette says in the documentary.

She adds later — with great sadness: “Honestly, he had it all. And maybe this is my resentment talking, but I feel like he threw it away.”

Kinkade died on 6 April 2012 at the age of 54; the coroner ruled it an accidental overdose of alcohol and Valium. A public spat further tarnished his wholesome image when the girlfriend he was living with at the time laid claim to his fortune and legacy, though the estate feud was quietly settled by the end of 2012.

When Kinkade’s devastated family entered his vault of art, they found what appeared to be physical manifestations of the suffering that had plagued him for years — paintings in dark hues with heavy themes, scenes of questioning and despair.

The works were a far cry from the light and nostalgia that made Kinkade a star; his daughters showcase examples from the vault in Art for Everybody, theorising about the practical and existential weights that fueled their father’s unknown creations.

“I feel very privileged to be one of the few people who’s seen those works in person,” Ms Yousef tells The Independent. “They’re so incredibly different from the ‘painter of light’ work. And ... an artist has to express themselves, and it’s so interesting to see the contrast between the kind of expression he was doing with the painter of light works.”

She believes “that conflict between wanting to be critically acclaimed and wanting to be commercially successful is one that defined his entire life and the work that he produced.

“And I also think that it is very common for artists all over the world, and over the ages, that everybody has that conflict — so he’s kind of universal, in that sense. And I think he was he was just a complex human being who was doing his best and was really torn about these things.”

The vault and Kinkade’s tragic trajectory expose a cruel reality that is clear with hindsight: While Kinkade was agonising over commercial success versus art-world acclaim, he was truly living the life of so many famously tortured artists who went before him. Did he realise it at the time?

Ms Yousef pauses to reflect and answers with carefully chosen words.

“I don’t know if he would have been necessarily aware,” she tells The Independent. “I think he was just really driven by the things inside of him ... I think he was split.”

He did, however, undeniably leave a legacy and a vast volume of work beloved by countless fans; Kinkade, unquestionably, will be remembered.

“It’s incredible to now think of what a visionary, and maybe a prophet, Thomas Kinkade was, when we see that every artist today wants nothing more than to have their image grace skin of an iPhone cover or a soccer ball or any of these things,” curator Aaron Moulton says in the film. “He understood how to disperse his image in a way more more advanced than anybody else — maybe even Warhol.”