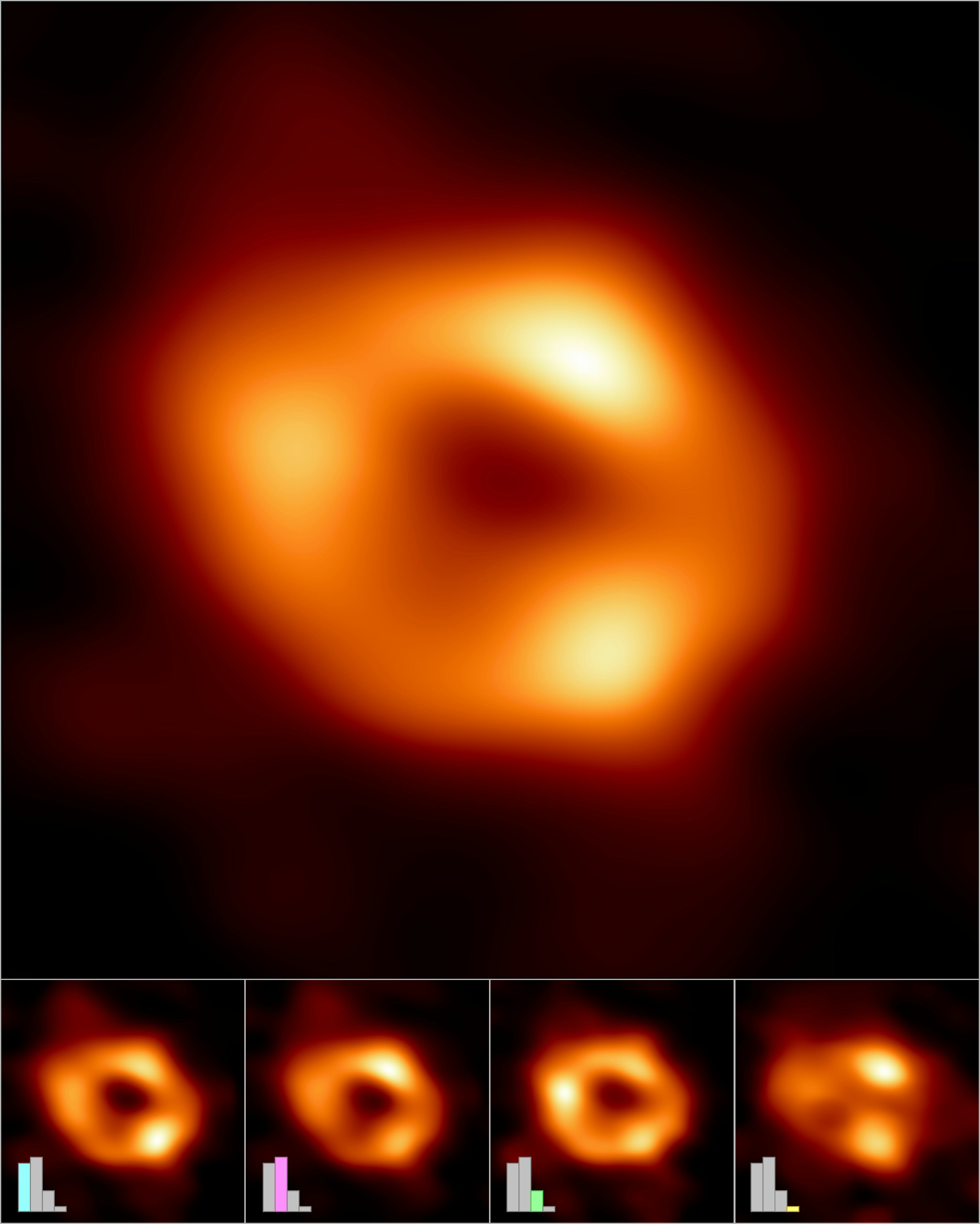

Black hole science is a little like shadow puppet theater. Black holes cannot be seen directly, because they trap all matter that falls into them, including light.

One way scientists learn about them, however, is by looking at the behavior of bright stuff surrounding the black holes. Sometimes, as is the case of the two supermassive black holes the world beheld through the incredible images from the Event Horizon Telescope, black hole shadows are flanked by the glow of superheated material whipping around it pretty continuously.

Other times, this isn’t the case. Single instances of illumination, called a transient, then do the trick to reveal the black hole’s nature. But a new paper published January 5 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters discusses one instance where a plot twist emerged from the dark.

In an unexpected surprise, one black hole released a flash two years after its first-detected one. It went “quiet” those couple of years because it was snacking on a star. And by not finishing its meal, the star lived to fly around the black hole, only to come back later and get slurped up some more by the black hole’s powerful gravitational field.

“I was extremely excited upon hearing that the source re-brightened so long after it went into a state of quiescence,” Eric Coughlin, study author and assistant physics professor at Syracuse University in New York, tells Inverse.

A transient is a source that rises and fades in brightness in the night sky on human timescales, Coughlin told an audience on Thursday during a presentation at the 241st Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

The puzzling flicker is a transient called AT2018fyk. It’s a repeating partial tidal disruption event, in which the signal seems to show something interacting with the black hole. The unknown object then stops and returns.

Coughlin’s goal on Thursday was to showcase a model that could potentially explain the peculiar transient.

Here’s the idea: An “unfortunate” star is providing a brief source of gas when the black hole shreds stellar material off it and superheats the stuff. Rather than plummeting to its complete demise, the star swings back out into space. Having lost some mass but still holding together, it survives the encounter and retreats from the black hole. But later, it swings by once more.

This work could help astrophysicists learn about the supermassive black holes that don’t have much material churning and glowing in their gravitational field. “Unfortunately, most supermassive black holes throughout the Universe — something like 98 percent — do not have a consistent supply of mass in this form,” Coughlin said at the AAS Meeting.

Directly detecting these dark black holes, he added, “is no simple feat.”

“I have studied tidal disruption events for some time, but they involve so many different pieces of physics and astrophysics that there is always something new to model and to learn,” Coughlin tells Inverse. “The next decade is going to be very bright — pun intended — for the continued study and discovery of tidal disruption events and other transient sources.”

.png?w=600)