Everything pointed to Li Li Qiao. It was her husband splattered across the kitchen floor, her fat, wet thumbprint on the hilt of the blade that lay next to him, and her blood-caked size 12 boots that had traipsed tremulously out the door not long after the crime was committed.

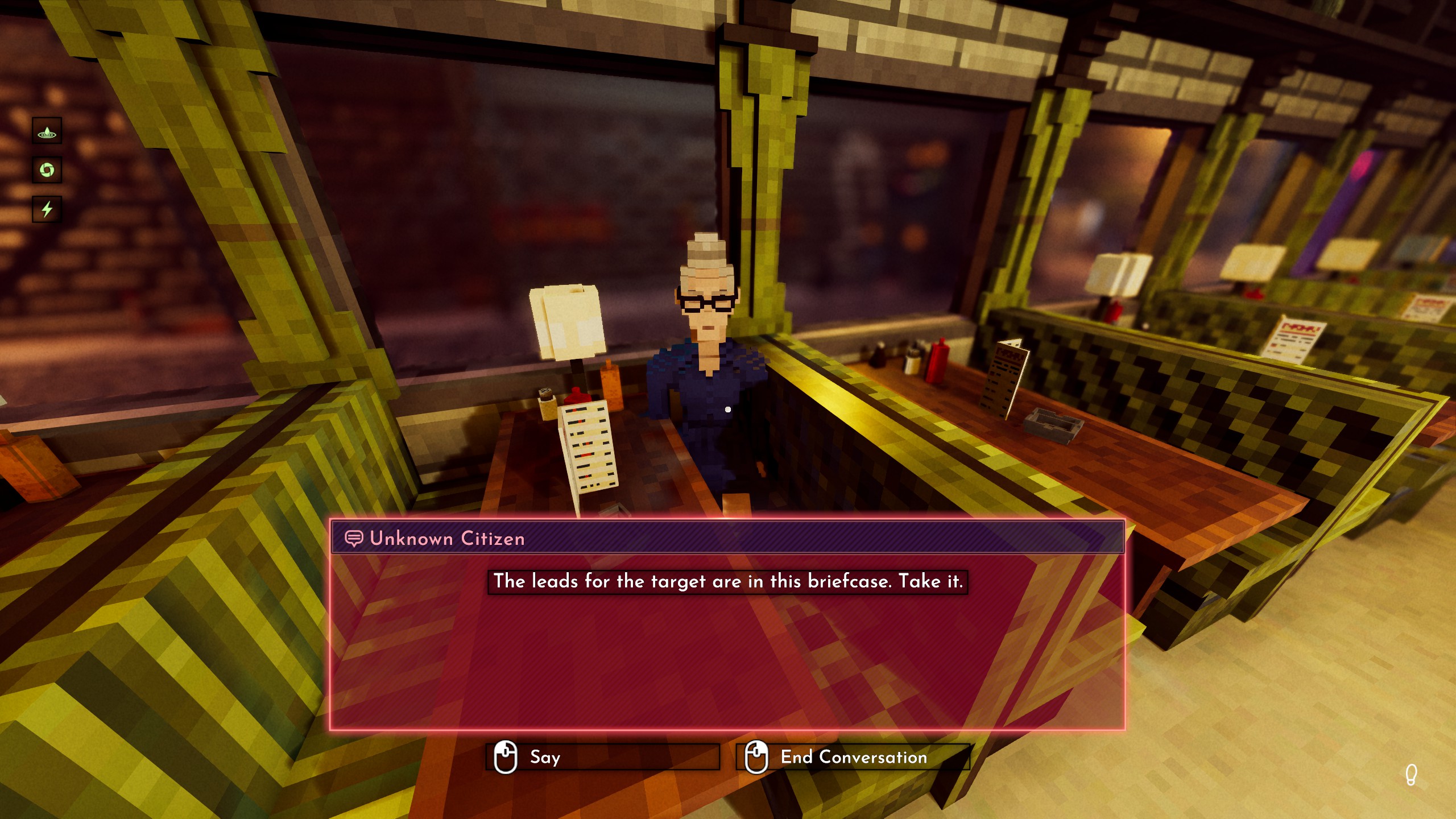

Her associates backed it all up: A chat with the neighbours revealed she'd been seen emerging from the apartment in a state of visible distress around 7 pm, smack-bang in the middle of the period that my cursory field forensics told me was the time the murder took place. When I visited her office (whose address I gleaned from a business card in the purse she'd left on the kitchen counter), I was told she failed to turn up to work the next day, and she hadn't returned since.

One coworker said they'd seen her haunting a nearby bar, though, and after quietly breaking into its security room via a well-placed air vent, I was able to ID her in the surveillance footage: Drunk, scared, and with a guilty conscience only drink could quiet. I just had to buy a beer and wait for her to turn up again. When I slapped the cuffs on, it didn't even feel like a victory. Just a full stop at the end of a short, sad story.

You can imagine my consternation when it turned out Li Li Qiao had committed no crime at all.

Amateur Sleuth

Shadows of Doubt, which is out on April 24 in early access, had led me up the garden path. The murder of Matthew Parker—Qiao's unfortunate husband—was just another in a line of crimes that the game had procedurally generated as I explored its world. The victims selected and evidence scattered according to the whims of an algorithm, red herrings and all.

Although I'm meant to be a hard-bitten cyberpunk private eye, picking up word of murders on the scanner and solving them for cash, I'd made a rookie error. I'd focused on the parts that did fit over the seemingly minor details that didn't. I couldn't explain why, for example, Qiao would drop an incoherent note ranting about a promotion next to the body of her husband, but I was sure it'd all come together in the end. More fool me. Hoist by my own procgen petard.

Even the largest option isn't much bigger than a city block, but Shadows of Doubt is going for depth, not width

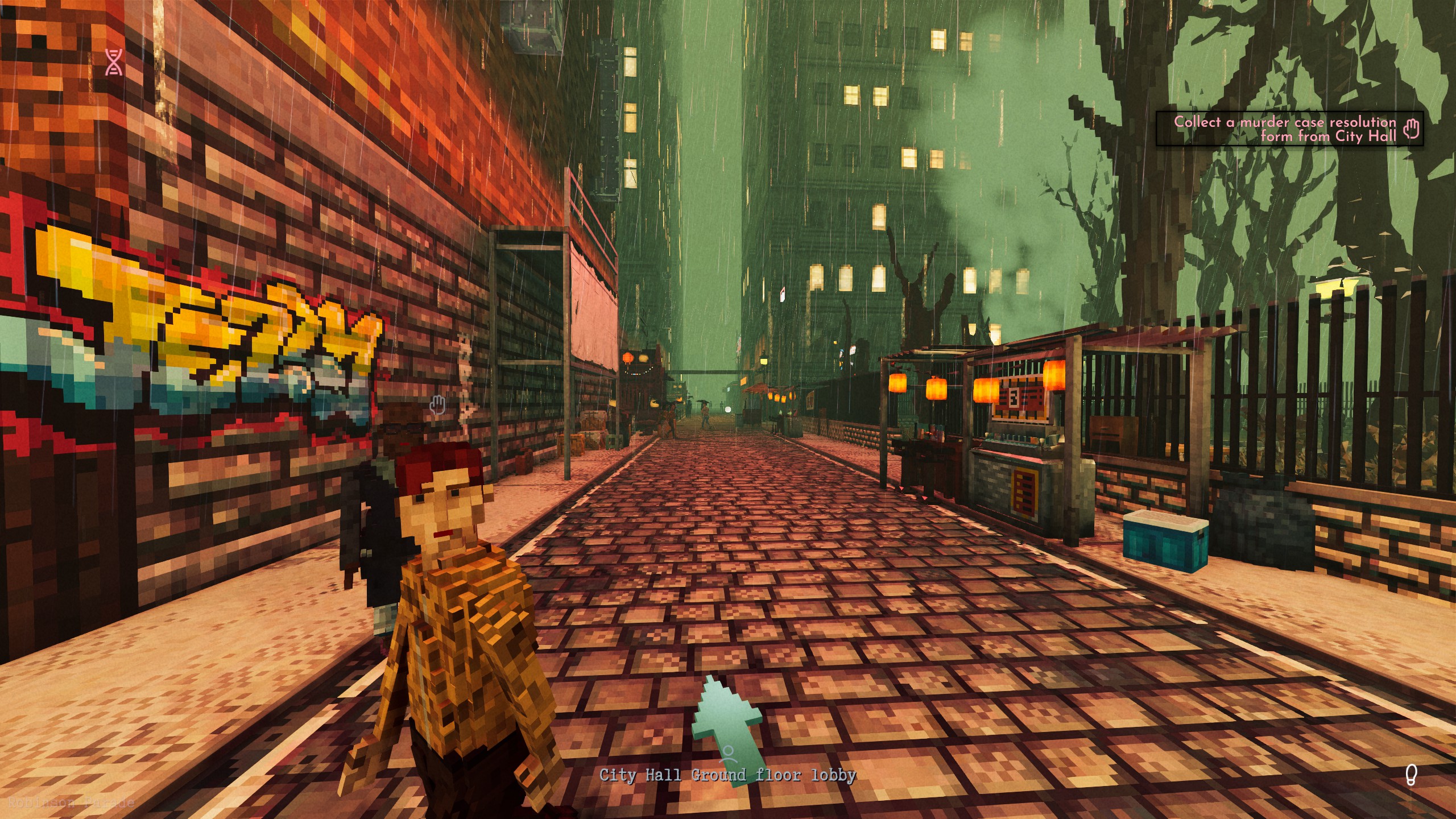

It's not just the crimes that are made up on-the-fly. The setting itself is too. Every time you hit new game, you choose a name and a size for your city and let the game conjure up a new stage for you to poke around in. Even the largest option isn't much bigger than a city block, but Shadows of Doubt is going for depth, not width.

Over the course of a loading screen, the game will generate street maps and building blocks, fill them with individuals with detailed personal lives (think jobs, schedules, partners and other relationships), and—because this is resolutely, determinedly an immersive sim—join everything up with a vast, random spiderweb of air ducts.

Voxel Noir

The game wears its Blade Runner inspiration on one sleeve and Deus Ex on the other. If for no other reason, ColePowered Games should be commended for finally putting money where Warren Spector's mouth is and trying to make the fabled "one city block dream game" that the System Shock and Deus Ex creator has spoken about for years. This game, with its rain-slick sci-fi noir presentation, multiple ways to solve problems, and fully-simulated populace is doing its damndest to see that vision realised.

A lot of it works well, even at this stage of development. The city, rendered in voxels, is eerie and beautiful. Shadowy figures stand backlit in doorways as they refuse to answer your questions, ghostly voices make promises from tannoys in Chinese and English, and the only sound in the apartments you scour for clues are the footsteps of neighbours and the hammering rain at the window.

Although I've run into a lot of graphical bugs—most of them minor—in this early access build, nothing has really broken that spell for me so far. The cyberpunk vibes are exquisite. This is a game that appreciates the buzz of a fluorescent bulb.

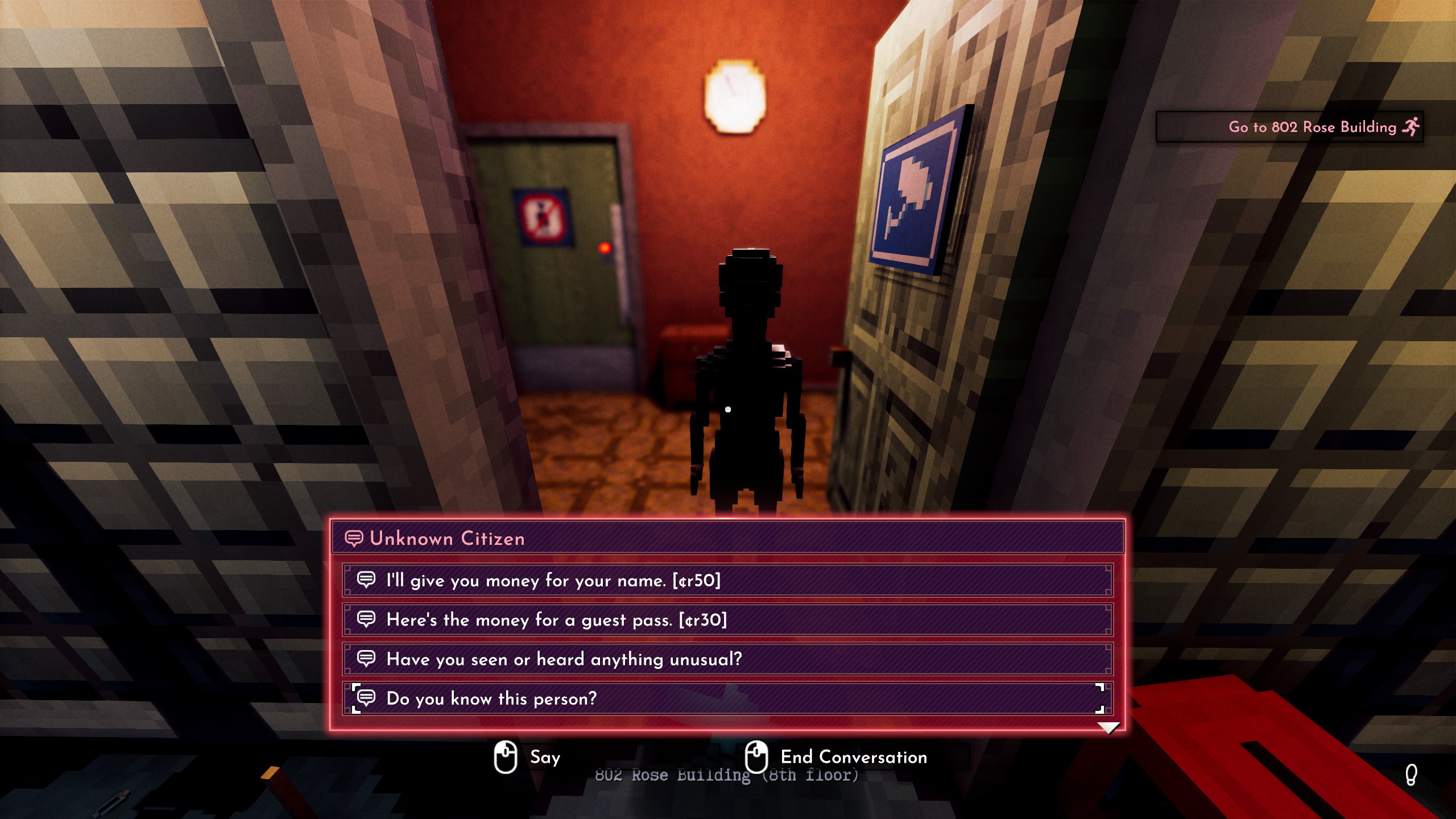

Solving the murders you're given is satisfying, too. Because every single person in your city has such a wealth of information attached to them, and all of it can be accessed by picking a lock, hacking a computer, bribing an NPC, or just bludgeoning your suspect into unconsciousness and taking their prints as they sleep, cracking a case becomes just as much a matter of divesting yourself of evidence you don't need as acquiring the info you do.

You get a classic conspiracy theory board—complete with red string between photographs—for every case you take on, and my first one became such a mess of names, dates, places, and codes that I eventually abandoned maintaining it and just kept the relevant details in my head.

I was more judicious with the ones that followed, and was rewarded with cases whose details were far easier to follow from A to B. Plus, there is a thrill to murmuring 'Gotcha' as you tie a single line of thread between a person, a time, a location, and a murder weapon.

Connecting the Dots

You don't have to be a detective, mind you. For as much as I was prepared to fill this piece with references to the great immersive sims Shadows of Doubt draws inspiration from—Deus Ex, System Shock, even a smattering of Dishonored—the game I found myself thinking about most often as I played was Introversion's Uplink, a free-roaming hacking sim from 2001.

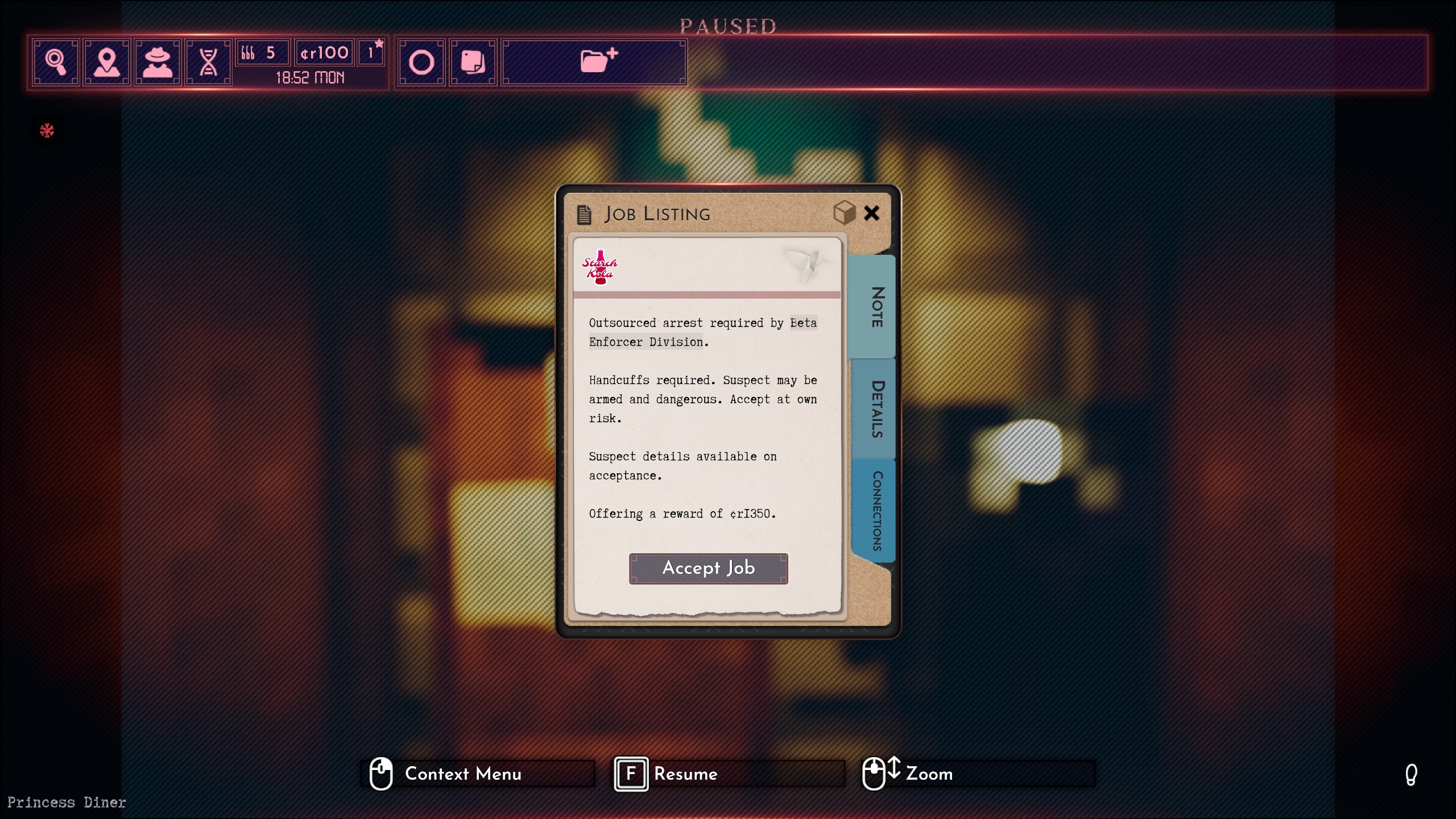

Like Shadows of Doubt, Uplink had a main thing it wanted you to do (Shadows will nudge you about murders, Uplink wanted you stop someone from assassinating the internet), but it also took place in a sandbox filled with all sorts of juicy and intriguing distractions, like vulnerable bank accounts and exposed servers.

Shadows is much the same, and it's easy to wile away hours breaking into the vaults of the local surgery clinics to steal the augmentations that lie within. Those augs aren't usually game-changers, by the way—the one I currently have installed pays me 40 credits for taking photos of restaurant toilets, which isn't exactly Dishonored's Blink—but they add little complexities to the game that are fun to play with.

Shadows even has an Uplink-like job board system—you can take on bitesize quests from cork boards in bars—if you need a quick payday.

So colour me very excited to see where this one goes. It's not perfect: There are plenty of bugs to iron out and shallow spots that could be deeper. In particular, I'd like to see the game's many, many NPCs given a level of agency that matches their level of detail. I don't mean a Dwarf Fortress level of incomprehensible psychological and physical depth (though I wouldn't say no) but right now the NPCs don't really feel like active characters in their world despite all the informational ephemera attached to them.

At least in the hours I've played so far, they just amble along their schedules. It'd be interesting to see them take a bit of initiative: Start new relationships, end old ones, get in fights, hand themselves into the authorities out of sheer guilt. Perhaps particularly violent or paranoid ones could up and decide to take out the nosy detective on their trail. Some of them might even decide not to keep their super-secret personal passcode written down on multiple post-it notes scattered about their home and workplace. But if a game doesn't have that, is it even an immersive sim anymore?

Even if its inhabitants stay as docile and scatterbrained as they are now, Shadows of Doubt is one of the most interesting games I've seen in years. But with some smart choices during its early access period—which is set to last six months, but could be lengthened depending on player feedback—it has the potential to be something much more.