In Adam Silver’s fever dream, the NBA is a wondrous world of wish fulfillment, a hooper’s utopia where everyone has an equal chance for success, a personal pathway to basketball nirvana.

Or, as Silver often said in 2011—when the NBA was wrangling with its players over a new labor deal—he envisioned a “system where all 30 teams could compete for a championship and create hope in every one of their communities.”

Depending on one’s vantage point, that mantra sounded either hopelessly idealistic or obnoxiously cynical—a contrived talking point to justify a financial battle that shut down the NBA for five months and nearly killed the season.

Thirty teams? With an equal chance to compete? In this league? Seriously? Well, yes, said Silver, who was the deputy commissioner then and rose to commissioner two years later.

“We would think that the players in this league would also want a system in which players on every team, if they play for well-managed teams, are on equal footing,” Silver said back then. “And I think it’ll create a better game.”

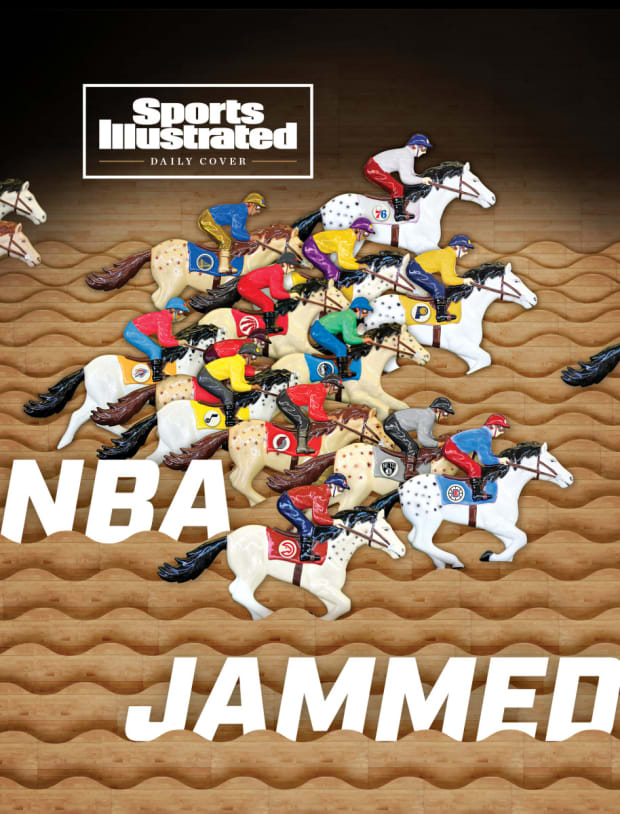

Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin; Steve Russell/Toronto Star/Getty Images

Eleven years later, those quotes still sound pretty fanciful. And yet, the NBA might be as close as it’s ever been to achieving something approximating parity, if not quite nirvana. In fact, by some measures, this season is shaping up as the most competitive we’ve ever seen. Just take a glance at the standings.

Out West, the star-studded Lakers are 10–13, 13th in their conference, and yet only five-and-a-half games out of first place. Just three games separate the top-ranked Suns (16–8) from the eighth-place Jazz (14–12). Out East, the Celtics (20–5) and Bucks (17–6) seem to be in a class of their own. But just four-and-a-half games separate the third-place Cavaliers (16–9) from the ninth-place Knicks (11–13).

Or consider this: As of last Friday, with the season at the approximate quarter pole, 17 of the league’s 30 teams were within three games of .500—i.e., either three games above or three games below. That’s the most in NBA history through a quarter of the season, per league officials, who provided the data at Sports Illustrated's request.

The league tracks parity through a number of metrics—from the relative “compression” of the standings, to the number of teams in playoff contention, to the preseason betting odds on the championship race, along with many other methods, says Evan Wasch, the NBA’s executive vice president of basketball strategy and analytics.

“What we’re seeing this year,” Wasch says, “is that across almost all of those metrics, we are seemingly at a historically high point in terms of that so-called parity.”

As in any season, there are a few teams that are clearly superior, and a few that are clearly hopeless. But it’s the middle that’s bulging like never before, bringing an uncommon volatility to the scoreboard each night and freshly scrambled standings each morning. That’s normal in the early weeks of a season, of course, but things usually stabilize by the 20- to 25-game mark.

“We’re clearly seeing something different this season,” Wasch says.

Since 1995–96, when the NBA expanded to 29 teams, an average of just nine teams have been within three games of .500 at the quarter pole. The previous high during that span? Fifteen teams in 2005–06. But most years there are somewhere between six and 13 teams hovering in that range at the quarter mark. There were only five as recently as the ’19–20 season. And a year ago at this time? Just 13.

Number of teams within three games of .500, year-by-year (per the NBA)

By more complex metrics (too complex to explain here), Wasch says this season’s standings are the tightest in the last three decades.

Is it all an anomaly? A momentary glitch? Will the trend even last through January, much less April? All impossible to know, of course. But something is afoot, and executives and coaches around the league think it’s significant.

“We’re all feeling it,” said an Eastern Conference general manager.

The why is much harder to definitively assess, though team executives and talent evaluators around the league all have their pet theories. (All were granted anonymity to speak freely about other teams and league policy matters.)

It’s the talent. “The NBA is as good as it’s ever been,” says a Western Conference executive, citing the surge in skilled young players, from Luka Dončić and Ja Morant to breakout star Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and the blossoming De’Aaron Fox. Of the league’s top 20 scorers, 12 are age 26 or younger.

“Drafted players entering the league are considerably more skilled than they were four years ago,” says another veteran team executive. He credited Stephen Curry for that phenomenon, because his otherworldly shooting has inspired a generation of young players to follow his lead. “He’s changed basketball. He changed college basketball. But most importantly, he changed youth basketball.”

The current top teams in each conference are being led by a 24-year-old (the Celtics’ Jayson Tatum) and a 26-year-old (the Suns’ Devin Booker). And meanwhile, some of the greatest stars of the era—Curry, LeBron James and Kevin Durant—are still playing at an All-NBA level in their mid-30s, creating a wonderful glut of top-tier stars.

“There is some passing of the torch, with Luka and Tatum and [Nikola] Jokić and Book,” says the Western Conference exec.

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

It’s the coaching. Multiple executives pointed to the leadership on NBA benches, saying that the acumen of head coaches, collectively, is also at an all-time high. Two first-time head coaches, both just 34 years old, are thriving this season: Boston’s Joe Mazzulla and Utah’s Will Hardy. “Coaching is significantly better,” says one executive, adding that the broad embrace of analytics also boosts parity, because “it ensures that under-talented teams are playing efficiently.”

It’s the friendlier schedule. Teams don’t play as many back-to-backs as they used to or travel as many miles as they once did, because of a years-long effort by NBA officials to optimize the schedule and make it less taxing on players. Team officials say there are fewer “schedule losses” baked into each season now, which perhaps helps less talented teams—who are more dependent on all-out hustle—to keep pace with more star-laden teams.

As a corollary, one team executive also pointed to the growing (if not entirely positive) trend of player rest and “load management.” When stars are routinely given nights off to rest and recover, it obviously benefits their opponents. There’s also a sense that injured players, especially the stars, are being given more time to recover than in the past. More missed games by top players means a better chance for upsets.

It’s the owners. This generation of team owners seems particularly intent on making win-now moves, even if it means landing in the dreaded middle—not great enough to win titles, not bad enough to get high draft picks. The Bulls, Kings, Wizards and Hawks have all made splashy trades over the last two years, sacrificing youth or draft picks, just to ensure they’ll be mid-level playoff teams. That aggressive approach might not get any of these teams to the Finals, but the urge to compete, rather than repeatedly tank for high draft picks, “is healthy for parity,” one executive says.

Speaking of that drive to the middle …

It’s the new lottery odds and/or the play-in tournament. Three years ago, the NBA adopted flatter odds for the draft lottery, with the specific hope of dissuading teams from choosing to be terrible. Two years ago, the league instituted a play-in tournament to give lower-ranked teams an incentive to chase the ninth and 10th spots each spring. It would appear both are having an impact.

“We think those are actually working really nicely together,” Wasch says. The shift in lottery odds—in which the team with the worst record now has only a 14-percent chance at the top pick, down from 25 percent—“has fundamentally eliminated the race to the bottom,” Wasch says. “I’m not suggesting we’ve solved the so-called tanking issue forever. But the notion that a team needs to have the absolute worst record in order to maximize their odds, it’s just no longer factually true.”

In theory, that means more teams are entering each season with more soundly built rosters, and perhaps with an eye on chasing a play-in spot the following spring. “I think you’re seeing teams approach roster construction a little bit differently as a result of [those changes],” Wasch says, “that there’s no longer a need to outcompete teams for losses throughout the season.”

Oddly enough, this is all happening the same year that the NBA is abuzz over a generational talent, Victor Wembanyama, who is a lock to be the No. 1 pick in June. If ever there was a time to tank, this is it. And yet some teams that were expected to tank—the Jazz, Pacers and Thunder—are instead some of the feel-good surprises of the early season. At least two of the teams on course for a top lottery slot—the Pistons and Hornets—opened the season with legitimate hopes of competing this season but have simply been derailed by injuries.

As with just about every NBA season, there’s a degree of unforeseen and unforeseeable factors at work, which means …

Maybe it’s happenstance? Look again at that fat middle, that bulging mass of good-not-great and bad-not-terrible teams clustered across the two conferences. A lot of them didn’t expect to be there.

The Timberwolves went all-in by acquiring Rudy Gobert in the offseason but are hovering just below .500. The defending champion Warriors have been shockingly average. The 76ers and Heat, who figured to be in the East’s top tier, are currently mired in the middle. The Kings and Trail Blazers, like the Jazz and Pacers, are far exceeding preseason projections. Three teams flush with marquee talent—the Lakers, Nets and Clippers—are all struggling to varying degrees.

“But nothing to panic about right now,” Clippers guard Reggie Jackson told The Athletic last week, with his team at 11–9, and he was absolutely correct, because they were just 2.5 games out of first as he spoke, despite everything, and the Clippers would soon get stars Kawhi Leonard and Paul George back from injury absences.

This sudden onslaught of competitive equilibrium comes on the heels of a superteam era that, for a time, made the NBA almost too predictable.

The Warriors and Cavaliers faced off in four straight Finals. The Warriors made five in a row. James personally made eight in a row, four each with the Heat and Cavaliers. In fact, only one Finals out of the last 16 did not involve either the Warriors, Lakers or LeBron James: the 2021 Finals between the Suns and Bucks.

Parity might have arrived even sooner, if not for Durant’s dramatic leap from the Thunder to the Warriors in 2016, fueling Golden State’s half decade of dominance while weakening their greatest rival.

The superteam model has waned over the years, though the Lakers and Nets are still clinging to it. The NBA’s adoption of a harsher luxury-tax system in 2011 has surely had an impact on roster building and talent retention. Players are changing teams more than ever.

It hasn’t quite created a 30-team race to the title but rather a league with fewer extreme haves and have-nots, a lot less black-and-white and “a lot more gray,” Wasch says.

Rocky Widner/NBAE via Getty Images

“There’s no one dominant team,” says an Eastern Conference executive.

A lot could still change: The Warriors, Heat and Sixers could regain their elite form. The Jazz and Blazers and Pacers could regress. Some struggling teams in the middle might pivot to tanking.

So it’s way too soon to declare this wondrous parity as the new normal. It might be “entirely anomalous,” Wasch concedes, adding, “we’re not going to celebrate too early.”

One thing has not changed since 2011. Now, as then, Silver is pushing to narrow the payroll gap across the league, to ensure the richest teams cannot simply outspend their small-market rivals. As recent reports have indicated, the league is once again advocating for a hard salary cap in its next labor deal—a position that will of course be staunchly opposed by the players union.

But that’s a story and a battle for another day. In the meantime, Silver can sit back in his Midtown office, gaze out across the NBA landscape and smile at the beautiful sea of gray.