Israel will no doubt continue to pour scorn on the international court of justice (ICJ) in The Hague in the days and weeks to come. “Hague Shmague” was the first response from the security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir. But the provisional measures ordered by the world court today are historic, by any measure.

The requirement that Israel must take steps to prevent genocidal acts, prevent and punish incitement to genocide, and report back on its actions within a month, will all have rippling implications – not just in the weeks but in the years to come.

The court has few powers of enforcement, as Russia and others have made clear. In its provisional measures on a case brought by Ukraine in 2022, the court called on Russia to immediately suspend military operations, presumably with little hope of being heard. Russia responded by demanding that the court throw out the “hopelessly flawed” case (spoiler: it didn’t). But that lack of enforcement doesn’t lessen the political discomfort for Israel – or for those who have seemed so ready to protect Israel from any and all criticism.

Until recently, the ICJ has toiled in the shadows. Other legal institutions in The Hague, like the Balkan war crimes tribunal which prosecuted Serb leader Slobodan Milošević and the international criminal court (ICC), which indicted Vladimir Putin, have enjoyed the spotlight. Until now, however, even when the world court addressed issues such as genocide in Bosnia or the legality of the Israeli “separation barrier”, its rulings barely made the headlines.

That has now changed, perhaps for ever. The rulings, all passed by either 16-1 or 15-2 – even the appointed Israeli judge, Aharon Barak, sided twice with the majority – are devastating for Israel, though a final judgment is still a long way off. Meanwhile, those governments which argued that South Africa’s case was empty and illegitimate now need to dig themselves out of the hole of their own creation.

Especially compelling was the evidence of incitement to genocide, a core element of the 1948 convention. A former director general of the Israeli foreign ministry and others had talked, even before the South African submission, of “extensive and blatant incitement to genocide and expulsion and ethnic cleansing”. But it was notable how many governments were reluctant to confront that self-evident truth.

Benjamin Netanyahu and his government like to use attack as the best form of defence. When the UN secretary general, António Guterres, criticised both the “appalling” Hamas killings and the civilian deaths in Gaza, while saying the former had not occurred “in a vacuum”, Israel’s ambassador to the UN called for him to resign. When the ICC, two miles across town, announced in 2021 that it was ready to investigate alleged crimes in Gaza, Netanyahu told Israeli viewers: “The state of Israel is under attack this evening”, and talked of “the height of hypocrisy”.

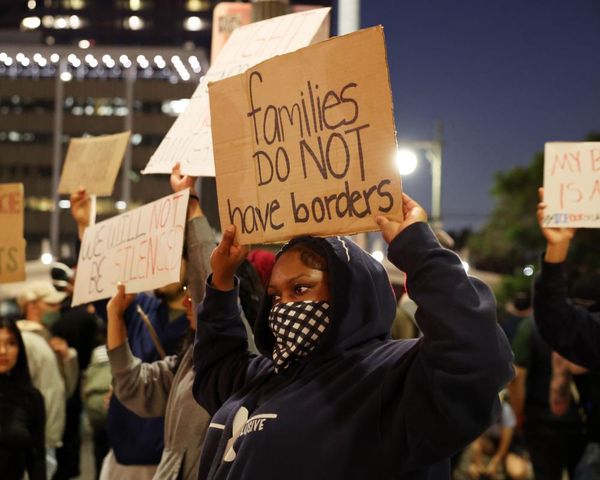

Such language will no doubt continue. But one problem for Netanyahu – and, by extension, for many western governments – is that millions of people around the world now see hypocrisy and double standards elsewhere in a very different context.

In 2021, Boris Johnson criticised the ICC’s cautious and much-delayed decision to look at Gaza on the grounds that an international court should not investigate Britain’s friends. The White House seems equally determined that an ally of the US should never be criticised – just as Russia was always determined to block any action on war crimes in Syria. The spokesperson of the US national security council didn’t wait for the judges’ interim ruling before describing South Africa’s case at the ICJ as “meritless, counterproductive, completely without any basis in fact whatsoever”. No hindsight is needed to realise that the optics of such an aggressively pro-Israeli statement were bad, never mind the absurdity of “no basis whatsoever”, which the judges’ rulings made legal nonsense of.

Washington’s reluctance to condemn the crimes and human suffering has most obviously been bad news for Palestinians. Although Netanyahu refuses to acknowledge that obvious truth, it is also bad news for Israel, whose future security is likely to be damaged for many years to come by what is happening now. But the implications also go well beyond this one conflict. The pick-and-choose approach to justice – “hypocrisy”, to use Netanyahu’s word – is dangerous for justice everywhere.

Most immediately, Ukraine has increasingly become the victim of a north-south divide through no fault of its own but directly resulting from the double standards so blatantly on show. Ukraine has tended to be supported by countries in the global north; Palestinians by countries in the global south. As Russia’s attacks across eastern and southern Ukraine remind us every day – and as I again saw for myself, for instance in the village of Hroza in October, where 59 villagers were killed in a targeted attack on a funeral wake – Ukraine still deserves and needs maximum solidarity. But, as a result of Ukraine’s own allies’ actions and inactions, Ukraine will now find it more difficult to gather enough much-needed support in its battles for justice, including the crimes-of-aggression tribunal that it has been pressing for in the past two years. Western governments have turned this into a case of “your victims” versus “our victims”, which it should never have been.

In November, Britain and five other countries joined in support of a Gambian case against Myanmar at the ICJ in connection with allegations of genocide against Rohingya Muslims. So far, so admirable. Anything that puts pressure on the junta in Myanmar – and a powerful judgment at the world court would certainly do that – is welcome. But the disconnect is blatant, if Britain can make such an intervention on Myanmar while refusing to address the fact that a key ally has killed more than 20,000 civilians in just a few months.

Most obviously, the world court ruling puts pressure on Israel. It rightly highlights the crimes committed by Hamas, which those who criticise Israel are sometimes too eager to put to one side. But it also serves as a reminder of the starting point for justice itself. Unequal justice is no justice at all. Nothing can be more destabilising than the lack of justice. That matters for Gaza, it matters for Ukraine, and it matters in conflict zones from Ethiopia to Myanmar. If The Hague court’s judgment helps kick western governments into an understanding of the need for a more balanced approach, that will be valuable. If they look the other way, not just the Palestinians but all of us will be the losers.

Steve Crawshaw is the former Russia and east Europe editor at the Independent, former UK director at Human Rights Watch, and author of Prosecuting the Powerful

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.