Hiding in Plain Sight tells the Holocaust story (and post-Holocaust life) of Mala Rywka Kizel – or Marilka Shlafer, as she became known later in life. But these are only two of the names by which she has been known.

Mala, a Polish Orthodox Jewish woman, was born in 1926, in Warsaw. She was just 13 when the second world war began. She spent the beginning of the war in the Warsaw Ghetto, participating in smuggling ventures, before escaping and going into hiding, passing as a Catholic.

She moved around, worked as a farmhand, was looked after by a committed Nazi family, the Mollers, became friends with antisemites, and fell deeply in love with Erich, a German plane engineer she met on a train platform who “was not a committed Nazi”, although he “wore the badge of Hitler’s NSDAP on his lapel”. She told Pieter van Os that Erich was “the love of my life” – a fact her Jewish husband, who she met at a shelter for Jews after the war was over, knew and accepted.

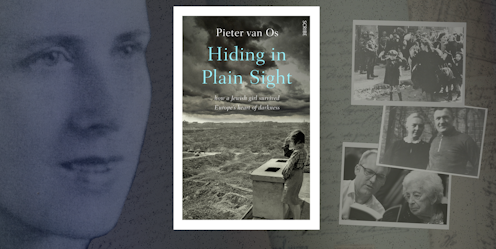

Review: Hiding in Plain Sight: How a Jewish Girl Survived Europe’s Heart of Darkness – Pieter van Os, trans. David Doherty (Scribe)

When going outside the ghetto walls to smuggle in food, Mala had “one distinct advantage” to help her avoid getting caught: her appearance.

Dobry wyglad, “good looks”, was the expression Poles used to describe Jews who did not look Semitic. Mala was fair-haired, and her eyes were blue with a hint of green. It also helped that she was a girl. Any boy with a suspect appearance or a Yiddish accent risked having his pants pulled down to see whether he had been circumcised. If a girl was stopped by the Polish police, they would make her recite a Polish prayer, something Mala could do without a trace of an accent.

Her escape from the ghetto was followed by years spent travelling, escaping, relying on some, evading others. This is not a Holocaust story of life in the camps, but one that follows the twists and turns of a young woman’s journey of trying to survive, and the necessary connections she made.

Pieter van Os – a journalist – interviewed Mala, at her Amsterdam home, several times (“welcomed […] with coffee and biscuits”) over the four years it took to put the book together. She also gave him access to her unpublished memoir, which he drew on, along with his own investigations.

I transcribed our recorded conversations, and then – with the transcripts and her memoir to hand – I set out on a journey through time, tracking down the cities, towns, and villages, the people and the buildings that figure in her story, looking for documents, books, and eyewitness accounts to provide more context.

He weaves together stories of Mala, her extended family and the people she encounters, with stories of the town, the community, and national events. Towards the end, he describes this as choosing “which side streets to wander down”. These wanderings provide context and depth. They remind us of the many journeys taken by many others.

He says:

Recalling events that expose the deepest abysses of human nature, she speaks with remarkable lightness, a tone I have never really encountered in writings or discussions about the Holocaust. […] Yet she trivialises nothing: her story traverses the abyss.

Read more: New research shows few Australians know about our own connections to the Holocaust

Always a foreboding

In this book, and others about the Holocaust we read now (in its aftermath), there is always a foreboding. We might not know exactly what will happen, but we know we are on the path to encountering brutal violence. This is heightened – or perhaps exploited – when we come to descriptions of how fluent Mala was in Polish, but that:

Yiddish was not only her mother tongue, but the language she spoke in her sleep when she was younger. In the story of her survival, this seemingly unimportant detail would put her life in the balance.

For we know that during the Holocaust, the seemingly unimportant or inconsequential could play a determining role in someone’s life or death.

There were so many ways to be murdered. “Of the 35,000 Jews who lived in Lublin before the war, only 230 survived the occupation,” van Os writes, describing how Jews were able to live relatively freely there until the Einsatzgruppen came through in 1942.

Reading these words when I did, a few hours before Kol Nidre – the evening service that begins Yom Kippur, or the Jewish Day of Atonement, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar – tore at me a little bit.

In Judaism, we say that to save a life is to save a whole world. Tonight I will stand in a community of Jews and attempt to account for my personal and collective errors, pondering how I and we can do better. Today I am reading about the murder of so many Jews, whose whole worlds I will never know. Stories of the war, of what people could not endure, never stop being painful.

This book is a meditation on evidence, history and memory. This is reflected by how Mala manages to live, the stories she can weave – and the truths, partial truths and mistruths she tells.

At one point, while hiding her Jewishness, the reader’s earlier foreboding is realised: Mala is heard speaking Yiddish in her sleep and dobbed in as a Jew by a man she had already distrusted. She is imprisoned in a camp for a few weeks while an investigation is carried out – but she is found to be German, not Polish or Jewish.

She is released to become a worker for the man who directed the camp; the two of them take a tram to an office in the city centre.

Mala filled in forms and was given a document that granted her temporary status as a stateless person. A racial assessment at a later date would determine whether she was actually an ethnic German. An immediate consequence of her new status was that she no longer had to wear a purple “P”. Mala had gone from Jewish to Polish to stateless.

Through stories like this, we learn the vagaries of national definition: the ways they are mutable and changeable – in certain circumstances. They are certainly never natural. But of course, Germany and its SS forces tried to naturalise and racialise nationality.

During the investigation into her nationality, Mala had to attend a testing centre where her blood was taken and she was quizzed on her family background by eight SS assessors. She spun them a tale. They found her – incorrectly – to be a Volksdeutsche, an ethnic German. It seems she may have been the only case of such an occurrence.

This was what led to her being placed with the German family (under the name Anni Gmitruk): as a Volksdeutsche, she was considered racially too superior to return to work as a forced labourer. The Mollers had lost two sons on the Eastern Front, so were glad to “do their part” and take her in.

After the war, Mala left the Mollers and returned to Poland, where she learned her family and friends had all been murdered. There, she enrolled (under her given name) at a shelter for Jews, where she met her future husband, Nathan. They were married by a rabbi on her 20th birthday, February 22 1946.

Together, with their young son, they emigrated to Israel in November 1948, quickly settling in Lydda (soon renamed Lod), a city that Israeli intellectual (and Zionist) Ari Shavit has called “the epicentre of the conflict over the existence of Israel”, claiming that “Zionism carried out a massacre in the city of Lydda” on July 12 1948 – just months before Mala and her family arrived there. “I was astounded that Mala had yet again found herself in the thick of ethnic cleansing,” writes van Os.

Nathan’s job with the local police was short-lived, after he was horrified by an assignment to patrol one of two segregated areas:

Barbed wire separated them from the rest of the city, and the 500 or so people fenced in were virtual prisoners. These were Christians and Muslims who had refused to leave when Lydda fell to the Jews, in addition to the inhabitants of local villages cleared by the Israeli army in the days that followed.

He refused. “Nathan had not survived the Lodz ghetto only to patrol the barbed-wire fences of the Lod ghetto.” Instead, with two friends, he tried to set up a cooperative to repair and renovate houses. This led to an ongoing job with the airline El Al.

He and Mala had their second child, a daughter, soon after arriving in Israel. They moved permanently to the Netherlands in 1979, after their daughter finished her military service and married a Dutchman. Mala died in 2020, at the age of 94 – five years after Nathan died, in an “old folks’ home”.

Read more: Moral ambiguity and the representation of genocide – is there a limit to what can be depicted?

Testimonies of trauma

Hiding in Plain Sight ponders evidence and historical narrative in other ways too. Every chapter ends with a section, “Instead of footnotes”, where van Os provides information about his research and hints at references.

Throughout the book we have moments such as:

Even by Polish standards, Mala recalls, the poverty in the region was abject. Research confirms this, although only scant historical data survive.

Of course, we all rely on numerous different types of evidence to tell our stories or create our arguments. But this way of setting it out – that “research”, presumably of papers and archives, confirms the testimony – works intriguingly not to support Mala as a truth-teller, but to undermine the power of her story as evidence in its own right.

Similarly, in talking about a scene Mala described having seen in a Nazi propaganda film, van Os writes, “Mala is mistaken. There is no such scene in the surviving copies” of the film. He then describes the film and its antisemitism. The more interesting and generous question, I think, is – why did Mala remember the film in this way? What did that scene do for her, whether it “really” existed or not?

When Mala hears stories after the war ends, she finds it hard to believe some of the atrocities. This is a problem many survivors have discussed: when they reported what had happened, what they had endured, they were disbelieved. This is always described as a unique kind of pain.

“Mala could not or did not want to believe” the story of babies being thrown from the third-floor windows of a hospital in the Lodz ghetto, van Os reports.

Germans would never do such a thing. She knew that; she had lived with a German family. It took her years to accept that this had really happened, after hearing the accounts of others and seeing them printed in black and white.

Famously, in his work on trauma, testimony and the Holocaust, alongside Shoshana Felman, Dori Laub recounts a moment when a woman who was in Auschwitz testified (in an interview for the Yale Fortunoff Archive) about seeing “four chimneys going up in flames, exploding […] It was unbelievable.”

At a later conference where this testimony is discussed, Laub recounts that some historians asserted that

the testimony was not accurate […] the number of chimneys was misrepresented. Historically, only one chimney was blown up, not all four.

This meant, for them, her testimony was “fallible”. But Laub – a psychoanalyst who had interviewed the woman for her testimony and who was present at this conference – “profoundly disagreed” and asserted instead that

the woman was testifying […] not to the number of chimneys blown up, but to something else, more radical, more crucial: the reality of an unimaginable occurrence […] The number mattered less than the fact of the occurrence. The event was almost inconceivable. The woman testified to an event that broke the all compelling frame of Auschwitz […] She testified to the breakage of a framework. That was a historical truth.

This is the pressing task for any of us listening to testimonies: to hear what they are saying, what they are testifying to, what truths they can hold. And also what they can never say, because some things will remain unsaid. As van Os writes, for instance, in his mention of the one woman from the town of Zerbst – the town where Mala ended the war:

she returned from a women’s internment camp in May 1945, unable to relay any information about the fate of the town’s other Jews. She had lost her mind.

The question of how to understand, how to write about, and how to approach testimonies of trauma is an important one. It is forever unsettled. Van Os does well in pushing us to continue to think about these questions, and not take anything for granted.

Hiding in Plain Sight is an utterly immersive book, bringing readers into lives and places and communities, into their loss and (re)building. It is a hard book to read. As it should be.

Jordana Silverstein does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.