On July 16, 1945, humanity carried out the very first successful atomic bomb test at the Trinity site in the desert of New Mexico. This plutonium-based device used an implosion-based design, which was replicated for the Fat Man bomb that was detonated a few months later over Nagasaki. Despite the fact that the massive device weighed about 5 tons, only a few pounds (or kilograms) was fissile material; the overwhelming majority was either the thick steel armor and case, as well as the high explosives surrounding the plutonium core designed to detonate the nuclear bomb.

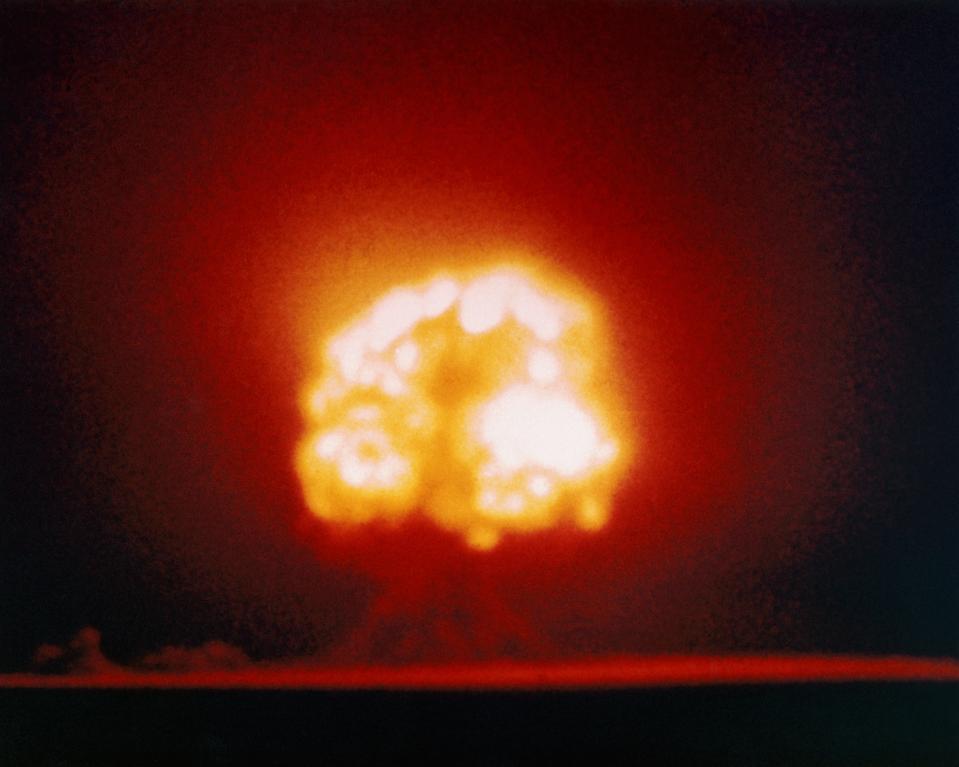

The explosion resulted in an unprecedented release of energy: the equivalent of some 20,000 tons of TNT. Even though it was detonated from the top of a high tower, the blast created a crater between 5-8 feet (1.6-2.4 meters) deep. And all around the land, a new type of mineral never-before created on Earth was created: trinitite. Here’s how it happened.

During World War II, the United States pursued a couple of different designs for a potential nuclear weapon, as no one had ever performed a successful nuclear detonation before. After constructing a near-solid spherical core where an aluminum shell would blanket a uranium slug that itself contained a plutonium sphere, made of two hemispheric components that were pressed around a tiny polonium-beryllium core.

The high explosives surrounding the aluminum shell should detonate and start the core compression, which would trigger the nuclear reaction inside. Atop a 100-foot (30 meter) tower, the bomb was placed. And at 5:29 AM on July 16th, 1945, the nuclear test was finally performed.

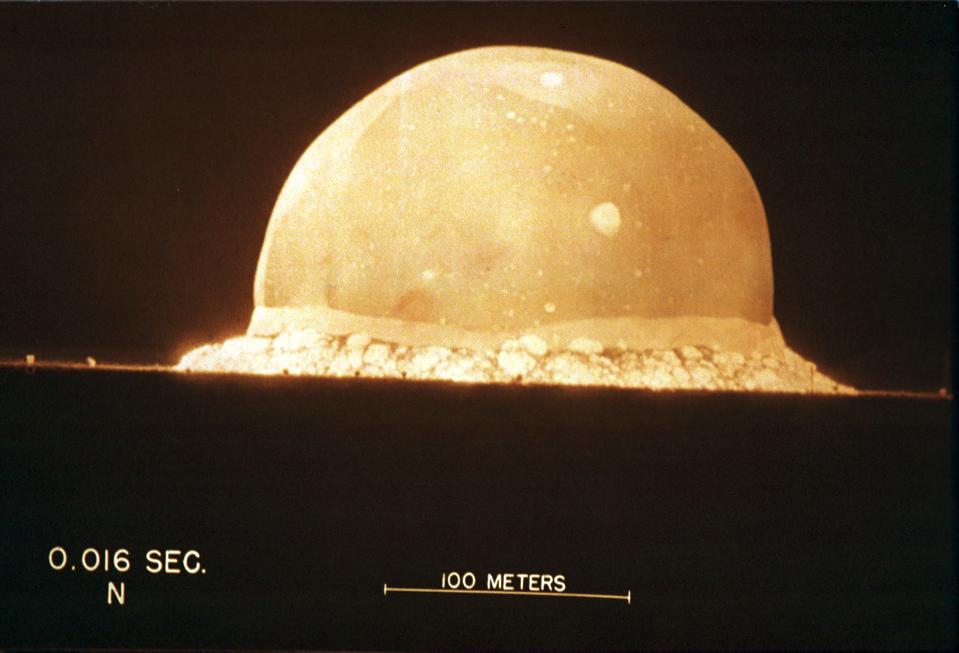

It’s often hard to appreciate how quickly energy gets released in something like a nuclear explosion. The shockwave from the initial blast was so powerful it was felt from over 100 miles (160 km) away, with the mushroom cloud reaching 7.5 miles (12 km) in height. The above photo, taken just 16 milliseconds (0.016 seconds) after detonation, shows a blast explosion about 660 feet (200 meters) high, but it’s what happened below, on the ground, that really was surprising.

Beneath the explosion location, an enormous crater formed. The landscape was incredibly scarred, and in many place, melted by the nuclear explosion. Because it was a fission bomb filled with plutonium and uranium, a variety of different isotopes and elements were strewn about into the mix. When all was said-and-done, what resulted on the ground below was something never seen before anywhere on Earth.

The desert sand melted under the incredible heat, creating a radioactive, green-colored glass known today as trinitite, from the Trinity test that created it. The silicate mineral was largely composed of quartz grain, feldspar, and with small amounts of calcite, hornblende, and augite mixed in. The temperatures and energies achieved had never before been reached on Earth, not even by an asteroid strike or a volcanic eruption.

Much of the trinitite that exists, though, wasn’t formed by the blast wave pressing down into the sand, but by sand which was drawn up inside the nuclear explosion itself, and then rained down in liquid form.

According to Clarence S. Ross of the USGS, writing in 1948 about the Optical Properties Of Glass From Alamogordo, New Mexico,

The glass, in general, formed a layer 1 to 2 centimeters thick, with the upper surface marked by a very thin sprinkling of dust which fell upon it while it was still molten. At the bottom is a thicker film of partly fused material, which grades into the soil from which it was derived. The color of the glass is a pale bottle green, and the material is extremely vesicular, with the size of the bubbles ranging to nearly the full thickness of the specimen.

The glass wasn’t a solid surface, but was rather fragmented into pieces of a wide variety of sizes. If you bring a Geiger counter near them, even today, you’ll here that continuous “clicking” sound: a telltale sign of continuous radioactivity.

The trinitite itself contains a mix of radioactive isotopes all throughout it that wouldn’t otherwise be found in nature. This includes, across a wide variety of samples, Cobalt-60, Barium-133, Europium-152 and 154, Americium-241, Cesium-137, Potassium-40, as well as Thorium-232 and Uranium-238. Material from the bomb, the metal tower (which was almost completely annihilated), and from irradiated minerals can all be found embedded inside this trinitite.

Unsurprisingly, this unique mineral was originally thought to be nothing more than simple, fused glass. The green, glassy substance known as trinitite became a collectors item, and was forged into jewelry from a time, before the dangers of radioactivity were realized. Once they were apparent, it became illegal to remove any material from the site, as the Atomic Energy Commission bulldozed and buried much of it, closing down the Trinity site to the public.

Over time, however, policies softened. In 1965, the site was declared a National Historic Landmark, and visitors can now go inside and check it out twice a year: on the first Saturdays of April and October. A few thousand people attend each semiannual opening, and you can still experience radiation levels that are 10 times as high as the normal background, and see small pieces of trinitite on the ground. (And although it is illegal to remove them, samples removed from the site in the 1940s can still be legally purchased.)

As beautiful, intricate, and interesting as trinitite is, the greatest hope of citizens all over the world is that nothing like it ever gets created again. Deep inside the mushroom cloud resulting from the atomic blast, sand, metals, bomb materials, and atmospheric particles all came together and went through all the normal stages of matter: from solid to liquid to gas and all the way to plasma.

Although the mixing wasn’t even throughout the mushroom cloud, fragments of practically all of the elements present can be found in what re-formed when the air cooled again. The glassy trinitite is what you get when the sand cools back down through the liquid phase, and then solidifies. The mineral itself is like nothing else on Earth, but is a stark reminder of the destructive capabilities that humanity possesses.

What is trinitite, then, really? It’s the first and purest example of radioactive fallout from a nuclear explosion. While simply heating sand to temperatures of around 1500 °C (2700 °F) is enough to create some very attractive fused glass out of it, the Trinity test vaporized practically every element within a quarter mile (400 meter) diameter sphere. This included elements with melting points far higher, exceeded by a localized energy release not seen by humans under any other circumstances throughout history. Nuclear detonations have unique properties, and this glass, although beautiful in its own way, is also a horrific reminder of the destructive power we wield, as well as its often-unforeseen consequences.

Trinitite will remain radioactive so long as our Sun shines. It’s up to us — the rest of humanity — to ensure that we never create anything like it again.

.png?w=600)