Thanks to devices like the Apple Watch or the Oura Ring, we’re able to track our daily habits in minute detail. But there’s another, far more unlikely user of these data-collecting devices: cows.

In recent years, researchers have designed special wearables for animals, too. While conservationists have given endangered species radio tracking collars for decades, advanced technology has now made its way to our furry friends.

In a ranch context, wearables can help keep tabs on livestock by monitoring, for example, their exercise levels, reproductive cycles, milk production, and signs of disease. But this tech usually relies on chemical batteries, which only last so long, may be hard to replace out in the field, and pollute nearby waterways.

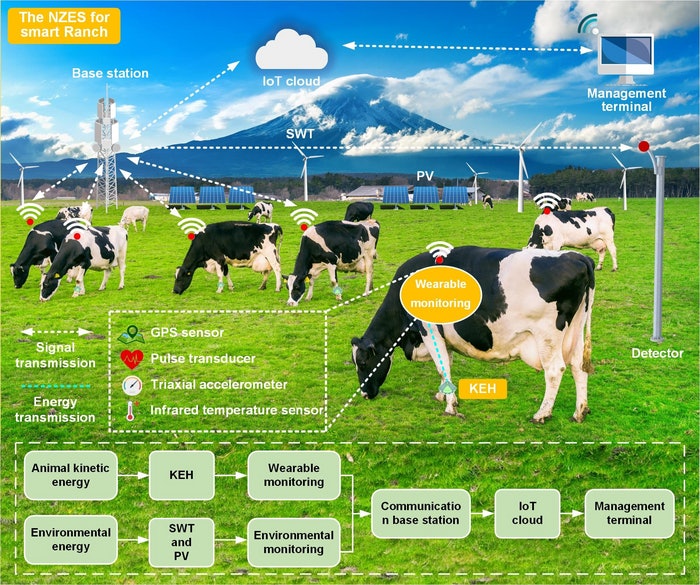

But what if cows could power their own wearables and eliminate the need for chemical batteries? That’s the idea for a new device created by researchers at Southwest Jiaotong University in China, according to a recent proof-of-concept study published in the journal iScience.

The proposed technology could “help improve the safety, intelligence, and visualization of the whole process of the food system,” says study author Zutao Zhang, a professor of mechanical engineering at Southwest Jiaotong University.

What’s new — The customized cattle accessory runs on kinetic energy, which is the energy generated from motion. Cows could don these small gizmos around their ankles and necks and feed power to sensors when walking and trotting about. These sensors could send ranchers data including the cows’ GPS coordinates, infrared temperature, and pulse.

Here’s the background — This isn’t the only energy-harvesting wearable in the works. Scientists have looked into gadgets that can capture and run on solar energy, wind energy, and radio frequency, among other sources.

In recent years, labs have made headlines for concepts like a shirt that can charge phones with sweat, foot-monitoring smart shoes that power up as you walk, and even a tiny strip for your finger that could follow your personal wellness.

Zhang’s new wearable concept fits into the broader push for “smart” farms and ranches, which link networks of wireless sensors and can give operators a full picture of how things are faring. This framework is called the Internet of Things, which you can technically set up in your own home with tools like smart thermostats, air quality monitors, and — perhaps one day — sensor-equipped toilets.

What they did — When thinking up a design, Zhang and his team took the unique ranch environment into consideration. They knew weather shifts would make it challenging to have a reliable and consistent flow of solar or wind power needed for accurate, real-time sensor measurements.

Cows themselves can only provide two types of power: heat energy and kinetic energy, Zhang says. From previous research, he learned that the former can’t create much juice. So he got to work on a special device that can turn cow trots into electricity through a process called electromagnetic energy harvesting.

It works like this: When a cow moves, a pendulum inside the wearable swings between a series of magnets. To create electricity, conductive coils cut through this magnetic field. These animals aren’t super active, so the pendulum is designed to enhance their movement. Once the energy is captured, it’s stored in a lithium battery and can be used to power sensors.

To see precisely how much juice cows could generate, the scientists found that the cow movement could theoretically power sensors for about two days before the wearable needed a recharge.

Electromagnetic energy harvesters tend to be relatively bulky, but Zhang says it’s important not to disrupt the wearer’s movement. Reducing the size comes with trade-offs, though.

“Charging efficiency is a problem,” says Yu Song, a medical engineering postdoctoral student at the California Institute of Technology who studies self-powered wearables and wasn’t involved in the new study. “They only use a very small energy harvester and the capability is not that high.”

Song notes that the energy harvesters could also incorporate piezoelectric materials, which can create electricity when strained, or triboelectric materials, which transfer electric charges when rubbed together.

Zhang notes that he’s working to address the power problem by converting the device’s alternating current power into the stable direct current needed for sensors to work.

Why it matters — This invention could make it easier for farmers to keep track of their cattle without even stepping foot on a farm and help them avoid manually changing batteries. If the wearable design pans out, it could also be applied off the ranch.

The researchers also tested the wearable on people and found that a light jog could power a temperature measurement sensor in their device. “We see great potential for wearable kinetic energy harvesters in athletes and health care,” Zhang says.

Movement-powered wearables could track athletes as they dribble down a soccer field or hit the slopes and help improve their competition skills without worrying about frequent recharging. They could also be given to people in rehab who are recovering from an injury in order to help doctors come up with treatment plans, he adds.

Not everyone would benefit from a kinetic energy-powered device, Song points out. Some people in hospitals aren’t moving much, so another type of power source that can be stored in a battery, like sweat, may be better in those contexts. But Zhang notes that, like the cow wearable, power sourced from human movement could also be boosted with a pendulum mechanism.

What’s next — This study gauged how much energy these wearables could produce, but there’s plenty more work to be done. Now, the scientists have to continue ramping up electricity generation and figure out how to work sensors into the device. But Zhang predicts that it might not be too long before they come to cattle near you.

“At this stage, wearable energy harvesting technology is making rapid progress, and we believe that this technology will be commercially available on a large scale in the near future,” Zhang says.