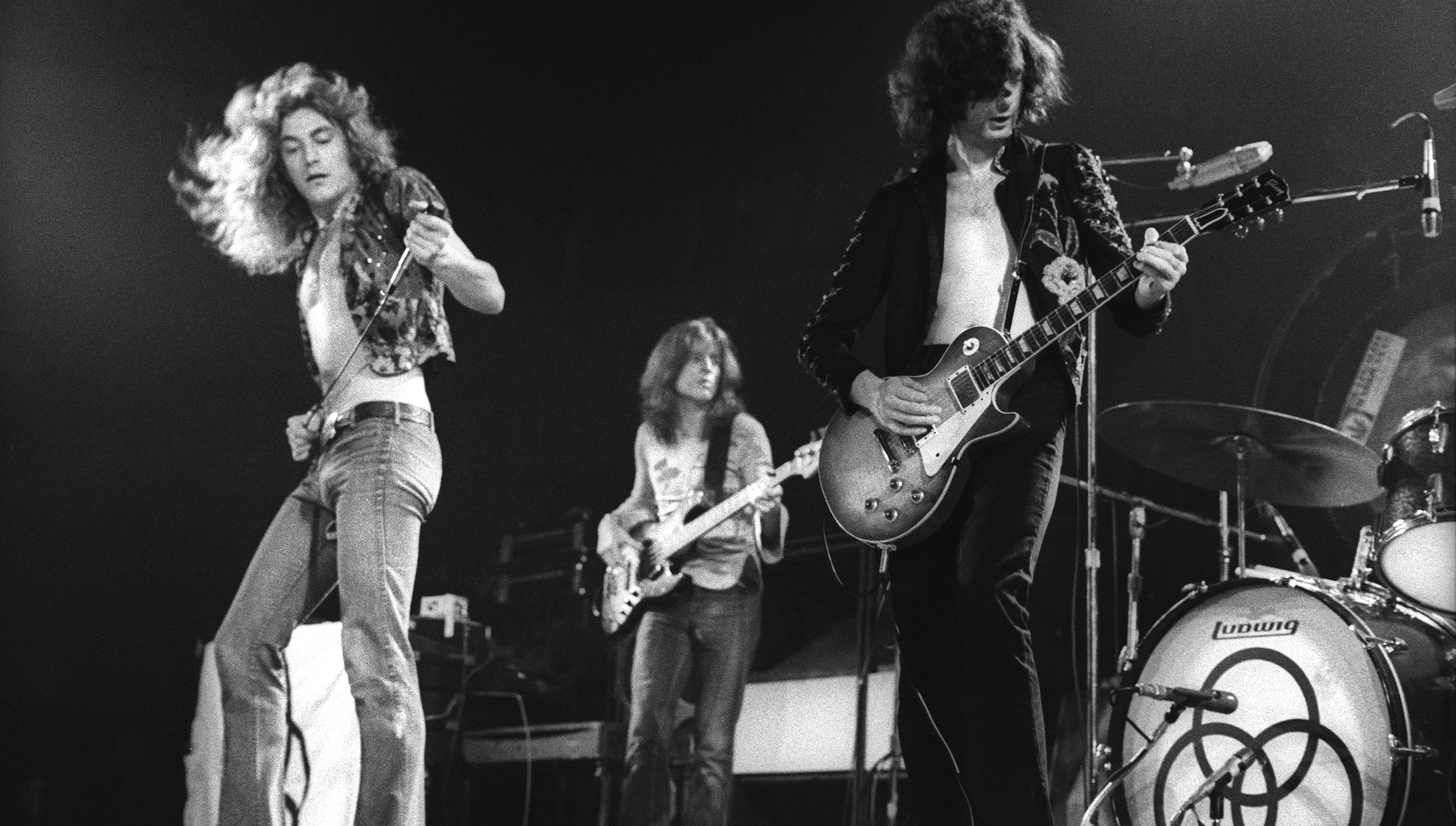

In homage to what is arguably hard rock’s most innovative group (and certainly its most influential), what follows is a tour of 50 of the most celebrated Led Zeppelin songs, with a focus on the guitar playing, songwriting, and arranging genius of the quartet’s visionary founder.

Compiling such a finite list presents tough choices for anyone, as the band’s recorded output of great music during its heyday was impressively prolific by any standard and includes well over 50 gems.

50. D’yer Mak’er (Houses of the Holy)

This lighthearted but heavy-sounding song, the title of which is intended to be pronounced “D’you Make Her,” was conceived as a playful melding of a Fifties doo-wop-style repeating chord progression and the quirky, syncopated rhythms of Jamaican reggae.

Page makes good use of sliding sixth intervals on the song’s verse riff, providing a thin-textured but catchy and harmonically effective accompaniment to Plant’s vocals. His guitar solo, like so many of his others, is noteworthy for its tasteful, lyrical phrasing and emotive use of bends and finger vibratos.

49. Tangerine (Led Zeppelin III)

Like Thank You, this folky ballad, written exclusively by Page, offers good bang for your musical buck, in terms of packing a lot of expression into a handful of melodically embellished open “cowboy” chords.

Page achieved a rich texture by performing the song’s main guitar part on a 12-string acoustic and handsomely decorated the chorus with authentic country-style pedal-steel licks, for which he used lots of oblique bends and a wah pedal to accentuate their weeping sound.

The chorus, played in the happy-sounding key of G, provides a welcome contrast to the somber feel of the verse and solo sections, which are in A minor. Also noteworthy is Page’s short and sweet slide solo, played with a thick, overdriven tone that effectively sustains his vibrato-ed notes and enhances their singing quality.

He thoughtfully describes the underlying chord changes in his slide melody by closely following the chord tones as he works his way up to the highest note on the neck.

48. Custard Pie (Physical Graffiti)

The opening track from Physical Graffiti features a punchy, Les Paul–through-Marshall–driven crunch riff behind Plant’s sexually euphemistic lyrics, many of which were borrowed from songs by early American bluesmen of the Robert Johnson era, specifically Drop Down Mama by Sleepy John Estes, Shake ’Em on Down by Bukka White, and I Want Some of Your Pie by Blind Boy Fuller.

Like Houses of the Holy, Custard Pie is built around a repeating two-bar riff based on an open A chord.

As in other songs, Page makes great use of rests in the song’s main riff, which allows it to breathe nicely and draws attention to the vocals and drums. Page’s penchant for jazz/R&B harmony is manifested in the G11 chord he plays – in place of the perfectly acceptable straight G chord – near the end of each of the song’s verses, which are loosely based on the 12-bar blues form.

The guitarist makes clever use of the wah pedal in his solo, which he begins with a repeating oblique-bend phrase that, with added wah-wah inflections, sounds like a toddler throwing a tantrum. The solo is also noteworthy for the way Page melodically acknowledges the chord changes by touching upon their chord tones as opposed to simply riffing away on the key’s major and minor pentatonic scales.

47. That’s the Way (Led Zeppelin III)

Like Bron-Yr-Aur, this mellow acoustic song was inspired by the serenity and pastoral beauty of the Welsh countryside during Page and Plant’s working vacation at the remote Bron-Yr-Aur cottage in 1970.

The band performed the song live in open G tuning, but the studio version sounds in G flat, which is most likely the result of the instruments being tuned down a half step (or a possible manipulation of the tape speed in the mastering process, similar to what Page did with When the Levee Breaks).

Page strums the song with a pick and makes great use of ringing open strings within his chord voicings, even as he moves away from the open position. Particularly cool are the reverb-soaked pedal-steel licks that Page overdubbed, for which he alternates between major and minor pentatonic phrases – again, a fine example of “light and shade.”

Also noteworthy is the climbing outro progression, for which Page again combines open strings with notes fretted in the middle region of the neck to create unusual, lush-sounding chord voicings.

46. In the Light (Physical Graffiti)

Page broke out his violin bow once again and put it to great use in this song’s extended intro, providing a low, eerie, sitar-style drone as a backdrop to Jones’ mystical, echoing “bagpipe” melodies, creatively conjured on a synthesizer.

Also particularly cool is the ominous-sounding descending blues-scale-based guitar riff that comes crashing in at the end of the intro (at 2:45) and the menacing, angular verse figure that follows, against which Page overdubbed a twangy, ringing open G note, played in unison with the D string’s fifth-fret G and treated with a shimmering tremolo effect.

The song’s bright, triumphant-sounding final theme, introduced by Jones on a Clavinet at 4:09, stands in stark contrast to the hauntingly dark, minor key-based sections that precede it – another example of light and shade.

Also worth noting is the ascending major scale-based lead melody Page plays over the theme’s repeating progression at 4:25, and the way it moves in contrary motion to the descending bass line, a compositional technique regarded as one of classical music’s slickest moves.

45. For Your Life (Presence)

Page broke out his 1962 Lake Placid Blue Fender Stratocaster for this darkly heavy song about the excesses of drug use in the L.A. music scene, tastefully employing its whammy bar to create well-placed, woozy sonic nosedives.

The song’s midtempo groove features sparse and restrained but fat-sounding guitar-and-bass riffs that include wide, dramatic “holes of silence” that are crossed only by the drums, vocals, and a shaken tambourine.

The arrangement really starts to develop at 2:07, as Page introduces a more ambitious new riff in a new key that’s propelled by a short machine-gun burst of triplets that further enhances the tune’s earthy midtempo groove. Page’s solo, beginning at 4:17 is noteworthy for its melodic inventiveness, quirky phrasing, and wailing, drooping bends.

44. Friends (Led Zeppelin III)

As mentioned earlier, Page employed the same open C6 tuning on this song that he used on Bron-Yr-Aur (low to high: C, A, C, G, C, E), again employing the open strings as drones to create a mesmerizing, hypnotic effect.

In this case, Page is strumming heartily with the pick, as opposed to fingerpicking, and plays double-stop figures against ringing open notes to create hauntingly beautiful melodies, making extensive use of the exotic-sounding sharp-four interval (F# in this case), as well as the bluesy flat-three (Eb) and Arabic-flavored flat-nine (Db), conjuring an intriguing East-meets-West kind of vibe.

As he later did in The Rain Song and Kashmir, the guitarist moves a compact two-finger chord shape up and down the fretboard, played in conjunction with ringing open strings, in this case to craft an enigmatic-sounding octave-doubled countermelody to Plant’s vocals. As a finishing touch, a string ensemble, arranged by Jones, was brought into the studio to double and dramatically reinforce the countermelody.

43. Trampled Under Foot (Physical Graffiti)

Inspired by the cleverly euphemistic lyrics of Delta blues legend Robert Johnson’s 1936 composition, Terraplane Blues, and the funky grooves of James Brown and Stevie Wonder, this muscular song features Jones stretching out on a Hohner Clavinet keyboard and a hard-stomping, almost relentless, one-chord vamp that’s broken up periodically by a brief string of accented chord changes, over which Page plays wah-inflected, Steve Cropper–style sixth intervals.

Page uses his wah pedal very creatively throughout the song, and creates exciting aural images by treating his guitar with ambient reverb, backward echo, and stereo panning effects, especially toward the end.

42. Houses of the Holy (Physical Graffiti)

Built around a fat-sounding strut riff, this song is nothing but a good time. Particularly cool is the way Page and Bonham shake up the riff’s solid eighth-note groove throughout by playing off each other with quirky, syncopated 16th-note fills, such as those at 0:38 and 0:42.

Also noteworthy is Page’s resourceful use, during the verses, of progressively descending triad inversions on the top three strings (not unlike those used by Pete Townshend in the Who’s Substitute), which provide an effective contrast to both Jones’ angular bass line during this section and the meaty main guitar riff.

41. The Rover (Physical Graffiti)

This song’s sexy main riff, introduced at 0:23, embodies that trademark Led Zeppelin swagger, resulting from Page’s clever application of pull-down bends on the lower four strings, which he uses to scoop up to target pitches from a half step below and make his guitar sing, just as he had done earlier on the low E string in his main riff to Dazed and Confused and with whole-step bends in the previously mentioned Over the Hills and Far Away inter-verse riff.

The effect is accentuated in this case by the use of a phaser, which makes Page’s guitar sound almost as if it’s played through a talk box.

Also noteworthy are Page’s elegantly crafted, flamenco-flavored solo, and the decorative second guitar part heard during the song’s choruses, for which Page arpeggiates the underlying chord progression, in the process adding an attractive countermelody to the theme without obscuring Plant’s vocals.

40. Dancing Days (Houses of the Holy)

Page takes a riff-building approach on this light-hearted yet powerful rocker similar to that used by Keith Richards on many Rolling Stones classics, such as Brown Sugar, Honky Tonk Women, and Can’t You Hear Me Knocking.

Making great use of open G tuning (low to high: D, G, D, G, B, D) and the convenient one-finger major barre-chord shapes it affords, he uses his fret hand’s available middle finger, ring finger, and pinkie to add harmonic extensions and embellishments to index-finger barre chords.

Page’s fascination with the Lydian mode, specifically its s4 interval, manifests itself in a musically compelling way in both the song’s sassy intro riff and its punchy verse and chorus riffs, all three of which convey a strong feeling of tension-and-release, as the harmonically turbulent s4 resolves downward in each case to the stable major third.

Particularly cool is the soaring slide melody, a neatly executed overdub first appearing at 0:56, which requires quick position shifts and careful attention to intonation (pitch centering).

39. Bron-Yr-Aur (Physical Graffiti)

Conceived during Page and Plant’s legendary 1970 retreat to Bron-Yr-Aur cottage in rural Wales and recorded during the sessions for Led Zeppelin III, this ingenious fingerstyle-folk instrumental is performed in the same open C6 tuning as Friends (low to high: C, A, C, G, C, E).

Page weaves the tune’s melodic themes into an impeccably uninterrupted stream of forward and backward 16th-note arpeggio rolls across the strings, with lots of droning open notes and unisons creating a rich natural chorusing effect and a lush, pastoral soundscape that puts the piece on par with the works of renowned late 19th-century impressionistic composers Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

38. No Quarter (live version, The Song Remains the Same)

This fully realized, extended performance of John Paul Jones’ keyboard showcase piece packs the same kind of dynamic punch and slow-jam rhythmic drama as Since I’ve Been Loving You, and demonstrates both Jones’ and Page’s penchant for modal jazz and their respective skills at building extended, story-like solos over a one-chord vamp. (Incidentally, it is performed in standard tuning, a half step higher than the studio version from Houses of the Holy, for which the instruments sound a half step below concert pitch.)

Also noteworthy are the two jarring, prog-rock-flavored chords in the song’s pre-chorus, Bfadds11 and Efadds11, first heard at 0:58 and 1:06, respectively.

37. The Wanton Song (Physical Graffiti)

Like Immigrant Song, this composition’s main riff demonstrates how alternating octaves combined with a strong, syncopated rhythm can create a compelling, heavy-sounding riff, and it’s safe to say that it probably inspired bands like Living Colour and Rage Against the Machine to pen their similarly styled riffs.

And like Out on the Tiles and The Ocean, the use of wide, recurring holes of silence in the guitar and bass parts while the drums and vocals continue creates pronounced dynamic and textural contrasts, which add to the song’s appeal.

The instrumental interlude section that ensues after the second and fourth verses (at 0:59 and 2:03, respectively) provides a stark contrast to the raw power of the alternating-octaves riff, and introduces a surprisingly jazzy chord progression within such a heavy rock song, with overdriven diminished seventh chords – something few other rock guitarists outside of Yes’ Steve Howe or Dean DeLeo from Stone Temple Pilots would have the vision and daring to use – employed as harmonic pivots to modulate to new keys.

Page’s Leslie-treated minor-seven chord riff that ensues brings to mind the Isley Brothers’ 1973 R&B hit Who’s That Lady, and further demonstrates the breadth of Page’s stylistic influences.

36. How Many More Times (Led Zeppelin)

This lengthy final track from Led Zeppelin’s debut album and live set-closer in their early days was a favorite improvisational vehicle for the band, with open-ended jam sections that allowed Page to stretch out with scorching lead licks, reverb-drenched violin bow excursions, and wah-wah-inflected chord strumming.

As Page told Guitar World in 1993, the song “was made up of little pieces I developed when I was with the Yardbirds, as were other numbers, such as Dazed and Confused.” He adds, “It was recorded live in the studio with cues and nods.”

Embodying an eclectic blend of stylistic elements, the song features an interesting variety of rhythmic grooves, from a jazzy swing feel, to a straight-eighths funk beat, to a Latin bolero rhythm somewhat reminiscent of the previously recorded Jeff Beck instrumental, Beck’s Bolero, on which both Page and Jones had played.

35. Gallows Pole (Led Zeppelin III)

Led Zeppelin’s creative arrangement of this sardonic, centuries-old, storytelling Celtic folk song titled The Maid Freed from the Gallows begins very modestly, with Plant’s pleading vocals accompanied solely by Page’s quiet acoustic strumming.

It builds in stages to a full-blown bluegrass-style hoe-down with a mandolin and acoustic 12-string joining the fray midway through, followed by bass, drums, and, finally, banjo (played by Page) and overdriven electric lead guitar, on which Page cleverly plays major pentatonic licks to conjure the sound of a country fiddle.

The arrangement’s ambitious development is not unlike that of Stairway to Heaven in its magnitude, and creates a similarly dramatic effect.

34. Out On the Tiles (Led Zeppelin III)

This forgotten classic features another of Led Zeppelin’s signature octave-doubled, single-note stomp riffs, this one played at a faster tempo than most of their other similarly crafted songs, with Bonham grooving on one of his favorite funky drumbeats as Page and Jones lock-in on a tricky bass melody that drops an eighth note at the end of the first and third verses (at 0:24 and 1:40, respectively).

Particularly cool- and powerful-sounding are the accented pulled bends on the low E string between the A power chords in the intro riff. It’s also worth pointing out that this is one of the very few uptempo Led Zeppelin songs that does not include a guitar solo; it doesn’t need one.

33. You Shook Me (Led Zeppelin)

Led Zeppelin’s convincingly worthy cover of this Chicago-style slow blues song (written by Willie Dixon and J.B. Lenoir) showcases their thorough assimilation of and deep adulation for the style, and their ability to take it to the next level of intensity through each band member’s musical virtuosity and artistic depth of feeling.

Page’s slide work, performed in the challenging and potentially unforgiving mode of standard tuning, is impeccable here, as he shadows Plant’s vocal melody with spot-on intonation and coaxes sublime vibratos from many of his sustained notes.

Equally laudable is Page’s wailing guitar solo, played without a slide, for which he employed tape echo and epic reverb effects to create breathtakingly soaring trails of cascading, screaming licks during the solo’s and song’s climax.

32. Celebration Day (Led Zeppelin III)

This playful, uptempo rocker was built around a slinky slide riff conceived by Jones, the genesis of which he described in his column in Guitar World in July 1997: “I came up with the intro/verse riff to Celebration Day while playing and old Danelectro baritone guitar like a lap steel, using an unusual, low open A7 tuning (low to high: A, A, A, E, G, C#), a steel bar, and a nut saddle to raise the strings.” When performing the song live, Page would adapt this riff to standard-tuned guitar.

On the recording, Page crafted a complementary and similarly slinky bend lick to play over the song’s main A-riff following each verse (initially at 0:24).

Similar to what he later did between the verses in Over the Hills and Far Away, the guitarist uses pulled bends on the bottom two strings to reach up to the last note of each phrase he plays, in this case adding a bold, shimmering vibrato to each bend.

31. Four Sticks (Led Zeppelin IV)

Named after Bonham’s literal use of four sticks on the track (two in each hand), this indigenous dance–like song features exotic rhythms and harmonic modalities.

The arrangement is built around three guitar riffs, each incorporating an open-string bass pedal tone, or drone.

As mentioned previously, Page used, for the song’s primary riff, the same bending away from a unison trick he employed in his Whole Lotta Love riff, with equally haunting results. In this case, he strums the open G string together with that note’s fretted equivalent on the D string’s fifth fret and pushes the fretted G slightly sharp by bending it upward (away from the palm).

30. Thank You (Led Zeppelin II)

Before Stairway to Heaven or The Rain Song were ever conceived, this well-written, timeless love song displayed, along with Babe I’m Gonna Leave You, a sensitive, emotional side of Led Zeppelin, one that didn’t have to do with sexual lust or scorn. (Gee, what was George Harrison complaining about in commenting to Led Zeppelin that their songbook was lacking ballads?)

Layering tracks of acoustic and clean 12-string electric guitars, Page weaved a tapestry of warm harmony behind Plant’s tender, low-key vocals, and crafted an elegant single-note acoustic solo, one often celebrated and emulated for its melodic appeal by players such as Slash.

Also noteworthy in Thank You are Page’s melodic 12-string runs behind Plant’s vocals during the song’s final two verses, specifically at 2:31 and 3:14.

29. Bring It On Home (Led Zeppelin II)

Like their other blues covers, Led Zeppelin’s reading of this Willie Dixon blues song has their unique artistic, stylistic stamp all over it, from its funky bass-and-drums groove, octave-doubled single-note riffs, and Page’s soulful use of string bends, which, incidentally, Jones aggressively mirrors an octave lower on bass during the song’s main riff.

Page added to the riff, at 1:54, a decorative high harmony line, as he would later do with riffs in Black Dog, The Ocean, Achilles Last Stand, and other songs, in each case further building the arrangement and enhancing its appeal. His harmony notes here form sweet-sounding sixth and third intervals based on the E Mixolydian mode.

The song’s middle verse sections sport a particularly bad-ass guitar riff, first appearing at 2:04 and built around sixth-interval double-stops, again based on the decidedly bluesy-sounding E Mixolydian mode. Notice how Page divides and orchestrates this riff into two separate guitar tracks, which he pans hard left and right in the stereo mix, accentuating the riff’s call-and-response quality.

28. Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman) (Led Zeppelin II)

Following on the heels of Heartbreaker, this playful and more light-hearted rocker features some of Page’s most tasteful power-pop guitar parts. He recorded the song’s primary rhythm tracks on his Fender electric 12-string (the same guitar he used in the studio on Stairway to Heaven and The Song Remains the Same).

As in Heartbreaker, Good Times Bad Times, Communication Breakdown, and other songs, he liberally employs his go-to Hendrix-style thumbed chord grips, which, lacking the low fifth of a conventionally fretted major barre chord, add sonic clarity to his chord voicings.

Page’s solo in this song is short and sweet, featuring emotive bends and vibratos and culminating in one of his trademark chromatic climbs up the B string.

27. Going to California (Led Zeppelin IV)

Page also used open strings and unison notes to great effect on this acoustic folk masterpiece. Tuning both his low and high E strings down to D (in what is known as double drop-D tuning), the guitarist plays dreamy hypnotic arpeggio figures that feature lots of ringing, repeated notes played on different strings.

With its blend of English and American folk-guitar styles (think Bert Jansch meets Merle Travis), Going to California is a fingerstylist’s delight. Particularly compelling is the dramatic bridge section beginning at 1:41, played by Page in the parallel minor key, D minor. If you listen closely, you’ll hear two acoustic guitars fingerpicking different inversions of the same chords, thirds apart.

26. What Is and What Should Never Be (Led Zeppelin II)

Like Ramble On, this song is another masterwork study in dynamic and textural contrasts. Page begins each verse by strumming a breezy two-chord vamp using jazzy, George Benson–approved dominant ninth and 13th chords with a clean, mellow tone, as Jones plays one of his celebrated, brilliantly lyrical, complementary bass lines.

Taking advantage of the wide range of gain and overdrive afforded his Les Paul/non-master–volume Marshall tube amp pairing, Page cranks up his guitar’s volume on the choruses, resulting in a beefy crunch tone that perfectly suits the powerful riff he crafted for that section.

The song also features one of Page’s most tasteful slide solos, carefully executed in standard tuning and thus without the harmonic safety net that an open tuning affords.

25. The Ocean (Houses of the Holy)

On par with Heartbreaker and Black Dog, in terms of embodying that trademark Led Zeppelin octave-doubled single-note stomp groove, this song’s iconic intro/main riff demonstrates just how effectively heavy-sounding rests, or holes of silence, can be when sandwiched between notes in just the right places.

This riff, as well as the power-chord-driven and similarly punctuated verse figure, are made to sound even more dramatic by the ambient room sound surrounding John Bonham’s drums, to which Page, the producer, rightfully deserves credit, for his visionary use of distant miking techniques.

24. Rock and Roll (Led Zeppelin IV)

The ultimate hot rod–driving song and tribute to Chuck Berry, this uptempo, straight-eighths blues-rock anthem features irresistibly boogie-woogie-like rhythms and a killer guitar solo that begins with Page playfully pulling off to open strings before ascending the neck with a daringly acrobatic chromatic climb somewhat reminiscent of his climactic lead in Communication Breakdown.

Particularly artistic is the way Page lays back rhythmically during the song’s verses with sustained power chords, providing an effective, welcome contrast to the relentless eighth notes of the bass and drums.

23. The Lemon Song (Led Zeppelin II)

Borrowing from Howlin’ Wolf’s 1964 blues hit and eventual standard, Killing Floor, Led Zeppelin created a derivative work that became a classic unto itself, showcasing their own renowned Memphis soul–style interactive blues-rock jamming, dynamic sensibilities, and each individual musician’s fat tones.

Not content to just play the song’s climbing intro riff on his low E string, Page employs hybrid picking (pick-and-fingers technique) to pair each low melody note with the open B string, creating a pleasing midrange honk.

Also noteworthy in this arrangement is Page’s substitution, on the five chord in the song’s repeating 12-bar blues progression, of a minor seven chord, Bm7, for the customary dominant seven chord, which would be B7 in this case, creating a darker, more melancholy sound.

22. Babe I’m Gonna Leave You (Led Zeppelin)

Another acoustic masterpiece, this song features a bittersweet circular chord progression presented as ringing, fingerpicked arpeggios.

Particularly noteworthy is the way Page spins numerous subtle melodic variations on the theme throughout the song (check out the one at 3:40), sweetening the aural pot with dramatic dynamic contrasts.

This may be one of the most perfectly recorded and mixed acoustic guitar tracks ever. Notice how, in the song’s intro, the dry (up-front and un-effected) acoustic guitar is in the left channel while the right channel is mostly “wet,” saturated in cavernous reverb.

21. When the Levee Breaks (Led Zeppelin IV)

This track is revered for, among other things, its epic drum sound, resulting from the cavernous acoustics of Headley Grange and Page’s ingenious distant microphone placement, as well as his decision, as producer, to slow down the tape speed in the mastering process.

Led Zeppelin’s cover of this blues song, written and first recorded in 1929 by Kansas Joe McCoy and Memphis Minnie, also features great slide playing by Page in open G tuning (low to high: D, G, D, G, B, D). Due to the slowing of the tape speed, however, the pitch of the recording was lowered by a whole step, so the song actually sounds in the key of F.

Page performed this song’s two guitar tracks on his Fender electric 12-string. Its additional strings, in conjunction with the open tuning, enhanced the unison and octave-doubling effect of many of the notes in the guitar parts, which already incorporate unison notes.

The result is a huge wall of droning G and D notes with a natural chorusing effect that mesmerizes the listener in a way akin to the chorus chords in Kashmir.

20. The Battle of Evermore (Led Zeppelin IV)

For this mystical-sounding folk-rock gem, Page and Jones traded the instruments they play on Going to California, with Page taking up the mandolin and Jones strumming acoustic guitar.

According to Page, “The Battle of Evermore was made up on the spot by Robert and myself. I just picked up John Paul Jones’ mandolin, never having played one before, and just wrote up the chords and the whole thing in one sitting.”

Page’s mandolin sound on this song is epic, which is partially the result of his taking advantage of the cavernous, majestic natural reverb of the location where he recorded his tracks, which was in the foyer of a large, old stone house in rural Wales called Headley Grange. (This location, by the way, is where several other tracks on Led Zeppelin IV and Physical Graffiti were recorded, most notably Bonham’s drums on the aforementionedWhen the Levee Breaks.)

Page additionally doubled/layered his mandolin tracks on this arrangement and employed a tape echo effect, with a single repeat, timed to echo in an eighth-note rhythm relative to the song’s tempo, resulting in a continuous stream of percolating eighth notes.

19. Immigrant Song (Led Zeppelin III)

With its fiercely galloping rhythms, jagged backbeat accents, and ominous-sounding flat-five intervals, this ode to Viking pillage no doubt helped fuel the lustful creative fire behind hordes of heavy metal bands like Iron Maiden, Celtic Frost, and Mastodon that came of age in the years following the song’s 1970 release.

Particularly sinister-sounding is the way Page plays, during the song’s outro, an atypical second-position G minor chord shape over Jones’ C-note accents, in the process creating a highly unusual voicing of C9(no3).

18. Good Times Bad Times (Led Zeppelin)

This punchy opening track from the band’s debut album set the stage for Zeppelin’s juggernaut conquest of the world of hard rock.

Page octave-doubles Jones’ nimble, angular bass line on his slinky-strung Fender Telecaster, adding shimmering finger vibrato at just about every opportunity. The guitarist’s scorching, Leslie-effected lead licks, with their gut-wrenching bends and tumbling triplets, convey a man on fire and poised to win the West.

17. Nobody’s Fault but Mine (Presence)

Led Zeppelin’s turbo-charged reinvention of this traditional American gospel blues song was inspired primarily by singer and acoustic slide guitarist Blind Willie Johnson’s 1927 recording of it.

Zeppelin’s version is built around a mesmerizing, laser beam-like guitar melody, which Page played with distortion and a flanger effect and doubled, both in unison and an octave higher, with Robert Plant additionally scat singing the line, adding to its mesmerizing, bigger-than-life quality.

Page’s aggressive exploitation of string bending and vibrato techniques, in both the main riff and his solo, adds to the soulfulness of the band’s arrangement. Also noteworthy are Jones and Bonham’s lock-step bass-and-drum syncopations, which further add to the power and drama of the band’s arrangement.

16. Black Dog (Led Zeppelin IV)

Black Dog was built around a snakey blues riff, initially written on bass by John Paul Jones and doubled an octave higher on guitar by Page.

The rhythmic orientation of the song’s main riff to the beat has been the subject of heated debate among working musicians over the years, the point of contention being specifically where “one” is.

When pressed for an explanation, Page was vague. But Jones, in his Lo and Behold column in Guitar World in the December 1996 issue, states that this deceptive riff should be counted with the first A note – the root note of the song’s key and the fourth note of the riff – falling squarely on beat one. (Drummer John Bonham’s big cymbal crash on beat two is one of the things about this riff that throws a lot of people off.)

Page enhanced the riff later in the song, at 3:18, by overdubbing a parallel-thirds harmony line. In the 1993 GW interview, the guitarist noted, “Most people never catch that part. It’s just toward the end, to help build the song. You have to listen closely for the high guitar parts.”

Page and recording engineer Andy Johns tried a novel and ultimately successful experiment by triple-tracking the song’s rhythm guitar parts. As Page explained, “Andy used the mic preamp on the mixing board to get distortion. Then we put two 1176 Universal compressors in series on that sound and distorted the guitars as much as we could and then compressed them. Each riff was triple-tracked: one left, one right, and one right up the middle.”

15. Ramble On (Led Zeppelin II)

This song is all about contrasts, or as Page likes to say, “light and shade.” It begins with a mellow, folky acoustic strum riff pitted against a highly melodic Fender bass line for the verse sections, which lead up to a hard-hitting and highly inventive electric guitar–driven chorus riff.

Page broadened the definition of the term “power chord” here by using the seemingly odd two-note combination of root and flatted seventh (F# and E, respectively, played right after Plant sings “Ramble on!”), a pairing made even more unlikely by the fact that he plays it over John Paul Jones’ E bass note. The theoretical discord notwithstanding, it sounds great.

14. Black Mountain Side (Led Zeppelin)

Page spices up this traditional Celtic folk melody with East Indian musical flavors, hiring a bona fide tabla drummer to accompany him on the track and injecting his own fiery, Indian-style acoustic lead break into the arrangement.

13. In My Time of Dying (Physical Graffiti)

This 11-minute track was inspired chiefly by Blind Willie Johnson’s reading of the traditional blues-gospel song Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed, as well as a similarly titled rendition from the same era by Delta bluesman Charlie Patton.

Zeppelin’s inspired interpretation of the song features some of Page’s best slide guitar work (performed in open A tuning, low to high: E, A, E, A, C#, E), as well as one of the fattest-sounding drum tracks in this or any other band’s catalog, the result of Bonham’s unique touch and feel and Page’s miking and mixing techniques.

12. Kashmir (Physical Graffiti)

Played in DADGAD tuning, which Page had previously used to great effect on both the Yardbirds’ White Summer and Led Zeppelin’s Black Mountain Side, Kashmir is built around four mesmerizing riffs, three of which involve the use of open-string unison- and octave-doubled notes, which create a natural chorusing effect and a huge wall of sound.

Particularly noteworthy is the way Page overlaid, at 0:53, the song’s menacing, ascending riff – the James Bond–theme-flavored part – on top of the recurring descending sus4 chord sequence.

Page explained in the previously mentioned GW interview, “The descending chord sequence was the first thing I had – I got it from tapes of myself messing around at home. After I came up with the da-da-da, da-da-da part, I wondered whether the two parts could go on top of each other, and it worked! You do get some dissonance in there, but there’s nothing wrong with that. At the time, I was very proud of that, I must say.”

11. Over the Hills and Far Away (Houses of the Holy)

This song is another study in contrasts, specifically between English/Celtic-flavored acoustic folk and Les Paul–driven hard rock.

It begins with a playful, folk-dance–like acoustic riff, which Page initially plays on a six-string and then doubles on a 12-string, that gives way, at 1:27, to crushing electric power chords and a clever single-note riff, for which Page incorporates pulled bends on the bass strings (first heard at 1:37).

Particularly cool is the way the guitarist reconciles this electric riff with the strummed acoustic chords previously introduced at 1:17.

Also noteworthy is the grooving, James Brown–style funk riff behind the guitar solo and the rhythmically peculiar, harmonized, ascending single-note ensemble melody that follows at 3:00.

To top it all off, Page, the producer, concludes the song with a false ending. As the band fades out, at 4:10, a lone guitar emerges with a final variation of the folk riff from the intro, but all you hear is the 100 percent wet reverb return signal, which creates a mystical, otherworldly, far away effect.

10. Heartbreaker (Led Zeppelin II)

With its menacing, octave-doubled blues-scale riffs and sexy string bends, this song epitomizes the Led Zeppelin swagger.

Interestingly, the verse riff features Jones strumming root-fifth power chords on bass, treated with overdrive and tremolo, while Page alternately lays back on decidedly thinner-sounding thumb-fretted octaves – a signature technique heard in his and Jimi Hendrix’s rhythm guitar styles – and punches barre-chord accents together with the bass and drums.

Page recorded the song with his 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, which he had recently bought from Joe Walsh, playing the guitar through his newly acquired 100-watt Marshall amplifier. The song also showcases some of Page’s most aggressive, inspired soloing, including a free-form, tantrum-like a capella breakdown section.

Page recorded the breakdown while the band was touring the U.S., using a studio different from the one where the rest of the song’s tracks were cut. He was unaware that his guitar on that particular section was tuned slightly sharp of the rest of the tracks, which are at concert pitch. The discrepancy goes unnoticed to most listeners and only becomes obvious if one goes to play along with the entire recording.

9. The Rain Song (Houses of the Holy)

Performed in an unusual tuning (low to high: D, G, C, G, C, D) with lots of ringing open strings and unison-doubled notes, this beautiful song features a sophisticated chord progression that was initially inspired by George Harrison, who challenged Page to write a ballad.

After playfully evoking the verse section of Harrison’s Something on the first three chords of The Rain Song, Page veers off into an ultimately more ambitious and original progression.

Particularly inventive and cool sounding is the Hawaiian-flavored dominant-ninth chord slide that precedes the first lyric line of each verse.

When asked to explain why the studio version of The Rain Song is in the key of G while the live version, as heard in the film The Song Remains the Same, is in A, Page replied, “It surprises me to hear you say that, because I thought they were both in A. Okay, the [live] tuning is [low to high] E, A, D, A, D, E. The only two strings that change are the G, which goes up to A, and the B, which goes up to D.”

Page explained how he arrived at this unusual tuning. “I altered the strings around so that I’d have an octave on the A notes and an octave on the D notes, and still have the two Es,” he said. “Then I just went to see what finger positions would work.”

8. Ten Years Gone (Physical Graffiti)

Like The Rain Song, this heart-warming yet heavy ballad demonstrates Page’s intuitive harmonic depth and sophistication, as he employs jazzy, expensive-sounding maj7, maj13, min9, dim7, and maj6/9 chords as effortlessly as Burt Bacharach, minus the associated schmaltz.

The song’s instrumental interlude, which begins at 2:31, is particularly sweet and rich-sounding. It features a laid-back, phaser-treated lead guitar melody with soulful double-stops over a bass, drums, and clean, jangly rhythm guitar accompaniment. Also noteworthy is Page’s doubling of the chorus riff, first heard at 0:32, with an electric sitar.

7. Communication Breakdown (Led Zeppelin)

With its down-picked pumping eighth notes and syncopated power-chord stabs, this song’s urgent verse riff embodies the spirit of Chuck Berry–style rock and roll. Not surprisingly, it served as the quintessential prototype for both heavy metal and punk rhythm guitar.

Page’s piercing, well-crafted solo, with its climactic, chromatically ascending unison bends, is like Berry on steroids, and demonstrates that Page, on his new band’s freshman outing, was already thinking outside the box, both figuratively and literally (the physical “box” being a pentatonic fretboard shape).

6. Since I’ve Been Loving You (Led Zeppelin III)

Page’s impassioned guitar solo in this highly dramatic, Chicago-style slow blues song is among his most inspired and emotive. The song’s chord changes and structure are truly original, and in his rhythm guitar part Page plays an inventively slick turnaround phrase at the end of each chorus (initially from 1:06–1:12) that mimics a steel guitar, with a bent note woven into and placed on top of two successive chord voicings.

What makes this phrase so interesting and enigmatic is how, over the second chord, Dfmaj7 (played on organ by John Paul Jones) Page bends a C note up to D natural – the flat nine of Dfmaj7 – and manages to make it sound “right.” It’s something few musicians apart from Miles Davis would have the guts to do.

5. Whole Lotta Love (Led Zeppelin II)

This song has one of the coolest intro and verse riffs ever written. Not content to play it straight, as his blues-rock contemporaries might have done, Page inserts a subtle, secret ingredient into this part, giving it that x factor and a spine-tingling quality.

Instead of playing the riff’s second and fourth note – D, on the A string’s fifth fret – by itself, he doubles it with the open D string (akin to the way one would go about tuning the guitar using the traditional “fifth-fret” method), then proceeds to bend the fretted D note approximately a quarter step sharp by pushing it sideways with his index finger.

The harmonic turbulence created by the two pitches drifting slightly out of tune with each other is abrasive to the sensibilities and musically haunting, but the tension is short-lived and soon relieved, as Page quickly moves on to a rock-solid E5 power chord.

“I used to do that sort of thing all over the place,” said Page. “I did it during the main riff to Four Sticks, too.”

4. The Song Remains the Same (Houses of the Holy)

Like a getaway chase on a stolen horse, this ambitiously arranged song, with its galloping rhythms and fleet-footed solos, is guaranteed to give you an adrenaline rush. Particularly noteworthy is Page’s decision to overlay two electric 12-string guitars during the song’s opening chord punches, each playing different and seemingly irreconcilable triads, such as the pairing of C major and A major.

“I’m just moving the open D chord shape up into different positions,” Page told Guitar World in 1993. “There actually are two guitars on this section. Each is playing basically the same thing, except the second guitar is substituting different chords on some of the hits.”

He adds, “The Song Remains the Same was originally going to be an instrumental, like an overture to The Rain Song, but Robert had some other ideas about it!

“I do remember taking the guitar all the way through it, like an instrumental. It really didn’t take that long to put together – it was probably constructed in a day. And then of course I worked out a few overdubs.”

3. Stairway to Heaven (Led Zeppelin IV)

Jimmy Page trampled over two rules of pop music with this masterpiece: it’s more than eight minutes long, a previously prohibitive length for pop radio formats, and the tempo speeds up as the song unfolds.

Stairway is the epitome of Page’s brilliance as not only a guitarist, but also as a composer and arranger, as he layers six-string acoustic and 12-string electric guitars throughout the song in a gradual crescendo that culminates in what many consider to be the perfect rock guitar solo, performed on his trusty 1959 Fender “Dragon” Telecaster (his go-to guitar in the early days of Led Zeppelin).

2. Dazed and Confused (live version, The Song Remains the Same)

Clocking in at more than 28 minutes, this marathon performance marks the apex of this song’s evolution and showcases some of Led Zeppelin’s most intense jamming and collective improvisation in a variety of styles.

Page is at the height of his powers here, in terms of both chops and creative vision, never at a loss for a worthwhile musical idea. The otherworldly violin-bow interlude, beginning in earnest at 9:10 and spanning nearly seven minutes, is particularly inspired, and Page’s use of tape echo and wah effects in conjunction with the bow is absolutely brilliant.

1. Achilles Last Stand (Presence)

This epic, 10-minute song is Page’s crowning achievement in guitar orchestration. The ensemble arrangement, bookended by a swirling, unresolved arpeggio loop, really begins to blossom at 1:57, and from this point on, Page spins numerous melodic variations over top of the jangly, plaintive Em-Cadd9s11 chord progression that underpins most of the composition.

Interestingly, Page previewed this chord vamp in the aforementioned 1973 live version of Dazed and Confused that appears on The Song Remains the Same, beginning at 5:52.

Thoughtful consideration was put into the stereo image of each guitar track, which keeps the entire recording crisp despite the dense arrangement. The song also features one of Page’s most lyrical guitar solos (and one of his personal favorites).

This story was originally published in the January 2013 issue of Guitar World.