This election will be won by the Coalition and Prime Minister Scott Morrison if the economic models perform as expected – and they usually do.

A model refined in 2000 by then Melbourne University economists Lisa Cameron and Mark Crosby found that most federal election results in records going back to 1901 can be predicted pretty well by just two economic indicators.

And they are not the indicators that might be expected.

The growth in real wages in the year leading up to the election appears to have no effect on the governing party’s chance of being returned to power. (Which is just as well for the Coalition, because the buying power of wages has been shrinking.)

Similarly, GDP (which is shorthand for gross domestic product, the measure meant to encompass almost everything known about the state of the economy) turns out to be “not robustly correlated” with support for the incumbent government in Australia, although it is in the United States.

The only two economic variables that do matter, and they seem to matter a lot, are the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment, each in a different way.

For inflation, the higher it is, the more the incumbent suffers, as you might expect.

For unemployment, what turns out to matter is not the rate itself. High rates and low rates appear not to be sheeted home to the party in power. What is sheeted home, big time, is the change in the rate.

Voters reward lower unemployment

A government seen to have cut the unemployment rate gets rewarded, while a government seen to have pushed up the rate gets punished.

Cameron and Crosby find a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate cuts a government’s vote share by 0.58 percentage points.

And they find a wrinkle. In swinging seats, Coalition governments are likely to be punished if unemployment rises, whereas Labor governments are likely to be rewarded. They say their findings are “consistent with voters having the perception that the Labor party is more committed to lowering unemployment”.

In 2005 economists Andrew Leigh (the one who later became a Labor politician) and Justin Wolfers applied a slightly different model to the 2004 election. They found it got the result right, but under-predicted the size of the Coalition victory.

The model usually gets it right

In the latest edition of the Australian Economic Review, University of Queensland economist Hamish Greenop-Roberts applied the Cameron and Crosby model to the past four elections, the one Labor won in 2010 and the ones the Coalition won in 2013, 2016 and 2019. He found it picked the result three times out of four, putting it on a par with the polls and betting odds, which also got the result right three times out of four.

The crucial difference is the economic model got the results right in each of the past two elections – something the others conspicuously failed to do.

Read more: Economically, 2022 looks like an ideal time to land re-election

Asked this week what the economic model would predict for the current election, Greenop-Roberts notes that on one hand, unemployment is much lower than it was at start of this government’s term (and far lower than was expected), which the model says should help it get re-elected.

On the other hand, inflation is unusually high, which the model says would hurt.

What matters for predicting the outcome is the size of each move and how much the size of each move has turned out to matter in the past.

And it’s no contest. The effect of the dramatic cut in the unemployment rate (from 5.2% to 4%) is so big it more than outweighs the effect of the 3.5% rate of inflation, “setting the stage for the Coalition to be returned”.

Unemployment trumps inflation

So big is what has happened to unemployment that Greenop-Roberts says an inflation rate of at least 8% to 9% would be required to flip the prediction.

Whatever Australia’s official inflation rate is in the lead-up to polling day (there will be an update next Wednesday) it will very possibly above its present 3.5% but still be way short of 8-9%.

Or perhaps the model will be wrong when it comes to inflation. Greenop-Roberts points out that since the early 1990s, an entire generation of voters has entered adult life without experiencing serious inflation, and might either be alarmed by it or not understand the concept. This election might provide a test.

And it is possible this will be one of the rare elections in which the state of the economy fails to predict the outcome. Opinion polls did badly in the last election, but they might recover and they are suggesting a Labor victory. Betting markets did badly too, and are only just suggesting a Labor victory.

Polls, experts and even the model can be wrong

Experts often get it wrong. Greenop-Roberts points to a poll of 13 experts published two days before the 2019 election.

Twelve predicted a Labor victory. The only expert who didn’t predicted the Coalition would be forced to govern jointly with independents, a prediction some way short of the result, which was a comprehensive Coalition victory.

Read more: Morrison defends Warringah candidate as push to oust her strengthens

The reality is that this election will be fought seat by seat, and Greenop-Roberts has identified a new metric that might help predict those outcomes.

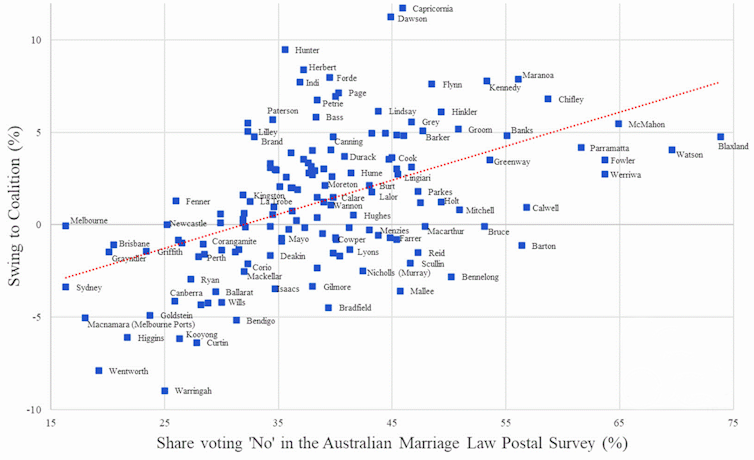

His Australian Economic Review paper compares the electorate by electorate results of the 2017 same-sex marriage poll with the electorate by electorate swing to the Coalition in 2019.

He finds the electorates that swung most to the Coalition in 2019 (shown below) were those most opposed to same-sex marriage.

‘No’ vote in the 2016 same sex marraige poll versus 2019 swing to Coalition

The statistically significant link better predicted voting intention than income, education or unemployment.

It might again, or we might not yet have perfected the science of predicting what will happen, which might be just as well. What’ll happen in this election is up to all of us.

Peter Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.