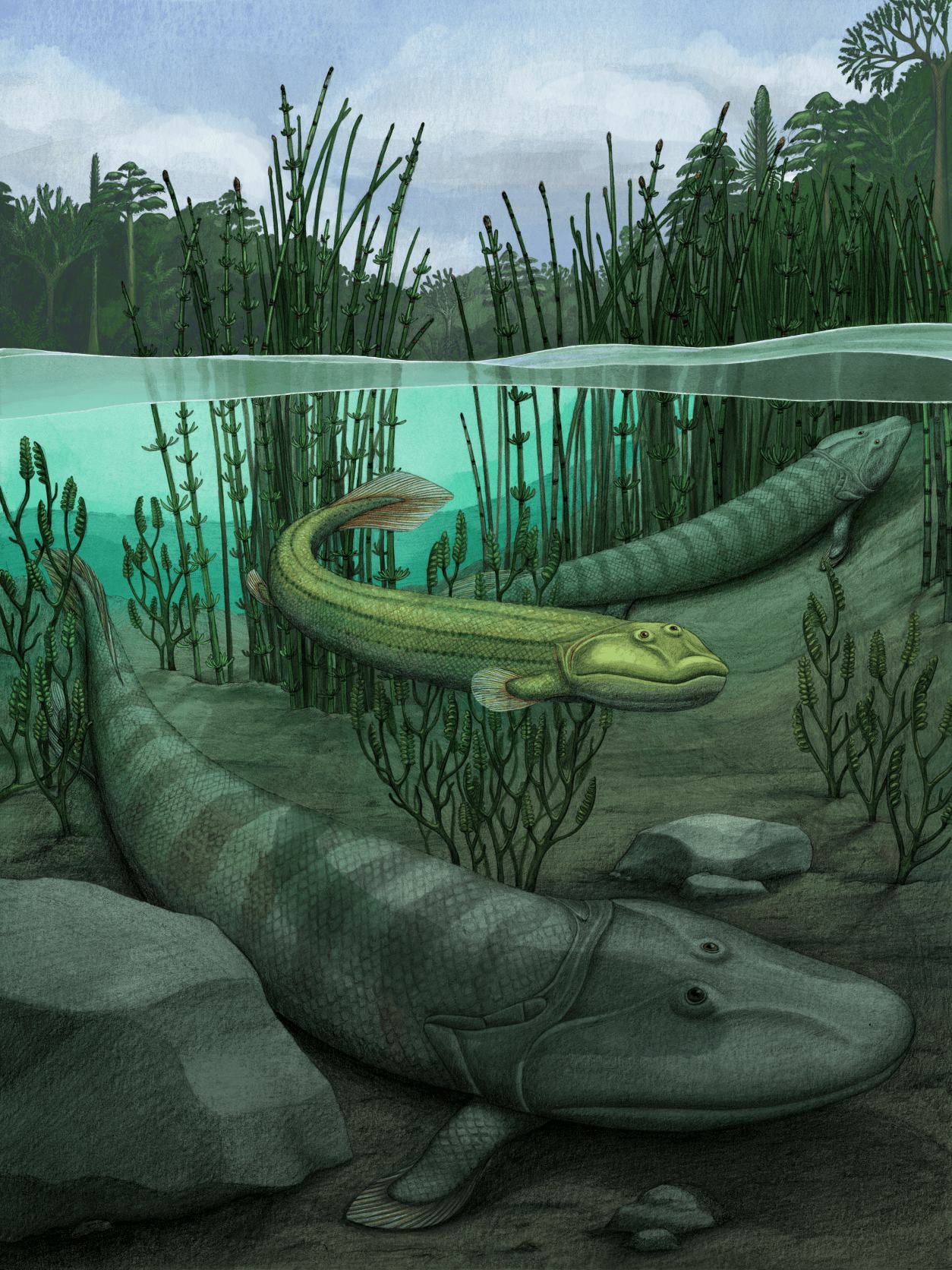

Some 385 million years ago during the Late Devonian period, a fish strolled from the water onto the shore in search of a new home. Its fins were robust enough that it could get around on land. Thus began the history of vertebrates on land.

Fast forward to 2004 in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut Territory, where researchers found two fossils about a kilometer apart. One came from a specimen later known as Tiktaalik roseae (pronounced tick-TA-lick). The other resembled a juvenile Tiktaalik, especially from the looks of its jaw. But nearly 20 years after its discovery, paleontologists suspected it was something else altogether.

Researchers from the University of Chicago and Drexel University recently published a study in the journal Nature in which they describe a new species of fish that may have preceded Tiktaalik.

What’s new — Researchers now deem the second fossil came from a new fish species they call Qikiqtania wakei. Pronounced “kick-kiq-TA-nee-ah,” the specimen’s name comes from the region where the fossil was found in the Qikiqtaaluk Region.

“It’s really rare to find an animal like this,” co-author Tom Stewart tells Inverse. “It's also exciting because some of the anatomy is unexpected.” He notes that some of the bone structure is very similar to our bodies. Stewart helped complete this research while at the University of Chicago as a postdoctoral researcher, and is now a biology professor at Penn State University.

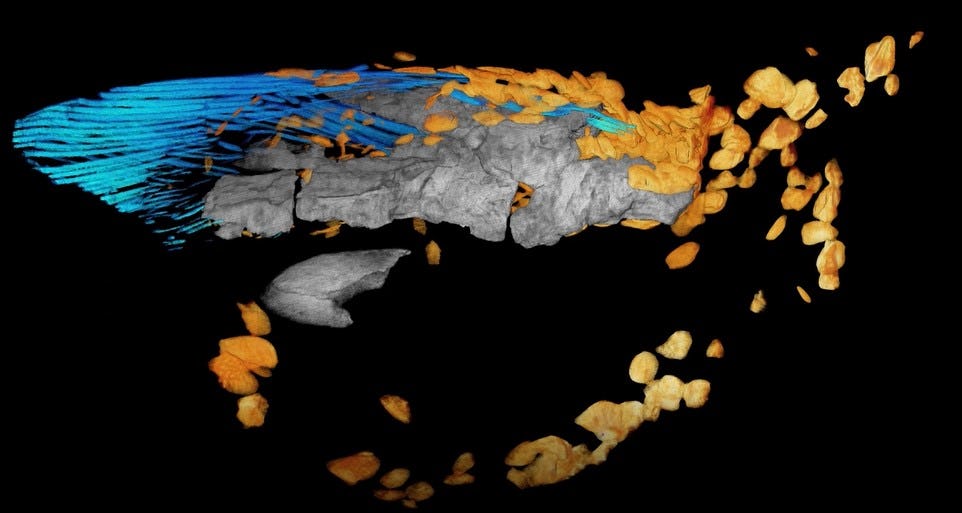

According to Stewart, this fossil has great pecs — or, at least one beautifully preserved pectoral and humerus, analog to our arm. The team had taken x-rays of the fossil using a CT scanner, which effectively allows them to see through the rock containing the fossil. That’s how they found the fully preserved fin, pectoral and all.

But it wasn’t until 2020 that the team thought it might be a different species. “We spent many, many hours processing all of the skeleton that we could say with great confidence, ‘Yeah, this is something different,’” Stewart says.

Why it matters — Qikiqtania adds further nuance to how vertebrates changed and eventually became land lubbers.

“This fossil is exciting because it gives a sense of the broader range of lifestyles of fishes at this part of vertebrate history,” Stewart says. These fossils’ rarity means that any addition fills a gap in scientific knowledge about these fishes.

Qikiqtania lacks some other features characteristic of other fishes from this time. For example, it had a large fin web to help control swimming. Fossils like Tiktaalik were more propped up on the ground on their fins either underwater or right at the water’s edge. “All of that together tells us that this was probably living a different type of lifestyle than something like Tiktaalik,” he says.

Digging into the details — Qikiqtania did not evolve into Tiktaalik, either.

“It’s totally normal to have two closely related animals that diverged from one another,” Stewart tells Inverse. “That doesn't mean that one came from the other.”

This is where statistical tests called phylogenetic analysis come into play. Stewart says paleontologists interrogate a bunch of fossils, asking which shared anatomy or scales or skeletal features. By constructing and visualizing how these creatures relate to each other, experts can build a phylogeny, or the “tree of life,” as Stewart puts it. In this early part of the tree of life, Qikiqtania is closely related to Tiktaalik as well as another Late Devonian fishy fossil called Elpistostege watsoni.

As for why these fishes changed habitats, that’s still a mystery. Stewart says these creatures could have been searching for more food or escaping predators, for example. The region had been a flood plain, so capable fish could wriggle on land and then led floodwaters to whoosh them to a new pond.

What’s next — Qikiqtania belongs within a larger context of tetrapods, which Stewart intends to further flesh out by examining anatomy.

“This, I would say is part of a broader set of studies trying to understand the biology, diversity, development and biomechanics of early tetrapods,” he says. “We have a new reconstruction of postcranial skeleton of Tiktaalik we’re working on that we think is really helpful for understanding how it lived and how it would have moved,” he says. This reconstruction could help us understand how the vertebrae and ribs relate to legs and other appendages.