Handwriting is dead. At least that’s what a New York Times article announced in 2023 in its postmortem investigation “What Killed Penmanship?” But there was no doubt about the culprit: technology.

You’ve probably heard something like this before: the more time we spend using our phone screens and keyboards to type out everything from emails and texts to grocery lists to wedding speeches, the less we put pen to paper and the worse our handwriting gets.

News articles over the past decade from the BBC, The Wall Street Journal and The Atlantic meditate on what we’ve lost by relying on typing alone, from meaningful thank-you notes to the basic skill of writing legibly altogether. Even those who once took pride in their cursive penmanship might now find their own handwriting all but impossible to read. As one CNN headline damningly asked: “Has Technology Ruined Handwriting?”

Articles like these imply that bad handwriting is a uniquely 21st-century condition, a symptom of our dependence on smart phones and laptops, one of the myriad ways our minds and bodies are being rewired by the ubiquitous technology that surrounds us. But as someone who studies the world of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, I’ve found that bad handwriting is not a new phenomenon at all.

Historical cacography

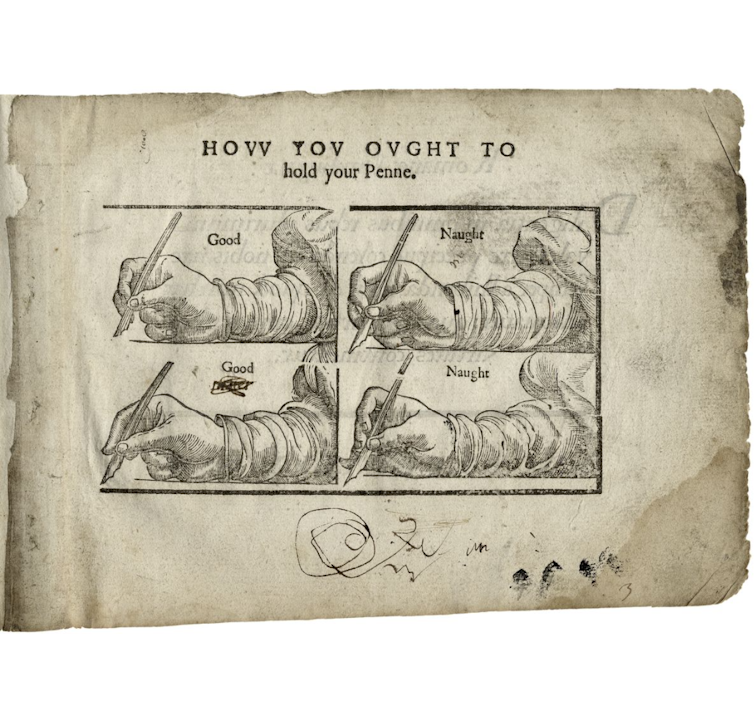

In 16th- and 17th-century England, the vast majority of documents were produced by hand. Even after the spread of the printing press in Europe transformed how books were produced, people still used ink and quill pens to write out the letters, financial records, legal contracts, marginal annotations and scattered jottings on which daily lives depended.

But even in an age when people frequently wrote by hand, messy and at times illegible handwriting was still a common problem. They even had a word for it: cacography, calligraphy’s evil twin.

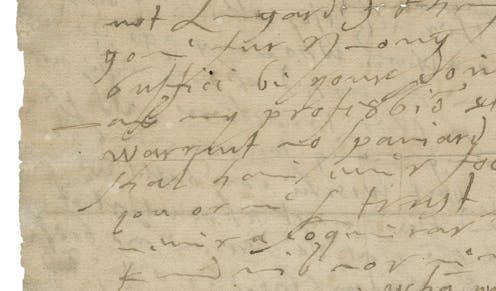

In countless letters that survive from the early modern period, writers apologize for their bad handwriting. Sometimes they blame it on circumstances: they were groggy from just waking up or tired late at night (“scribbled with a weary hand in my bed” reads one sign-off from 1585).

Sometimes the reasons were medical: a broken arm from falling off a horse, a hand injured in a duel or stiffening joints from the onset of arthritis or gout. Of course, a quickly dashed-off letter will always sacrifice elegance for speed. But some people seem to have had messy handwriting regardless of the circumstances.

Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, one of the most influential courtiers in the age of Queen Elizabeth I, became notorious for his bad handwriting, which one contemporary said was “as hard as any cipher to those that are not thoroughly acquainted therewith.”

The politician Sir John Glanville described his own handwriting as “so bad that hardly anyone but his own clerk can read it.” The brilliant Margaret Cavendish, author of the proto-science fiction masterpiece The Blazing World, said in the mid-1600s that she spent so much time writing quickly enough to get all her thoughts on paper that she lost the ability to write legibly altogether. “My ordinary handwriting is so bad,” she observed, “as few can read it.”

The Reformation theologian Martin Bucer allegedly couldn’t even read some of his own manuscripts. Nor was he alone. As the preacher John Preston observed in a sermon, “One would think a man should read his own hand, yet some do write so bad, that they cannot read it when they have done.”

In an age when corresponding in one’s own hand was an important gesture of intimacy, some self-conscious writers nevertheless found themselves depending on the services of professional copyists to make more legible transcripts of their letters.

The Dutch humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus told one of his correspondents that he had used a scribe “so as not to torture you with my cacography.” Those who did receive cacographic letters might deeply resent being so tortured: Sir Philip Sidney, Roger Manners, and the Lord High Treasurer William Cecil all complained to Sir Robert Sidney about his “evil” handwriting.

Too good to write well?

Bad handwriting, it seems, is timeless. Yet, its social and cultural meanings can also be shaped by specific historical circumstances. In early modern England, for example, at a time of comparatively low literacy rates, the ability to write legibly required education and training.

We might think then that elegant handwriting would have been seen as an index of social status. But the opposite could also be true: the aristocratic nobility were notoriously bad at writing by hand. Popular dramatists even made jokes about it. But bad handwriting may have been deliberate.

In fact, Shakespeare’s Hamlet says just that:

“I once did hold it, as our statists do,

A baseness to write fair, and labored much

How to forget that learning”

That is, elegant handwriting was a tell-tale skill of the upwardly mobile, not those who were born into power and privilege. Writing carelessly could be a way of asserting one’s social or political clout by forcing others less privileged to struggle to decipher what one had written. In other words, messy handwriting could be a power move.

Today, the ubiquity of smart phones and laptops has no doubt played a role in the ways we write. But for those of us who can’t read our own sticky notes and to-do lists, it may come as a relief to know that bad handwriting is not an unprecedented phenomenon, but has its own centuries-long history. We’re simply living a new chapter of it.

Misha Teramura does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.