Consider Abdul, a 26-year-old Darfuri refugee whose fellow villagers were burnt to death by Janjaweed, an Arab-supremacist militia. Think of Parwaiz, a cherubic 15-year-old Afghan boy with striking blue eyes, his father blown apart by a Taliban bomb. Or ponder the case of Hayat, who fled Eritrea – ruled by a regime that rivals North Korea for totalitarian repression – after his friends were arrested.

All of these are refugees I met in Calais, seeking to cross the Channel for British shores. All suffered horrors unimaginable to most people reading these words, and all would be automatically deported and banned from returning under Rishi Sunak’s new plans. When the Tory MP Neil O’Brien declares, “We must do whatever it takes to stop the boats,” you may doubt that he really means there are no limits to what this government is prepared to inflict on these traumatised human beings, until you remember they once refused to rule out using wave machines.

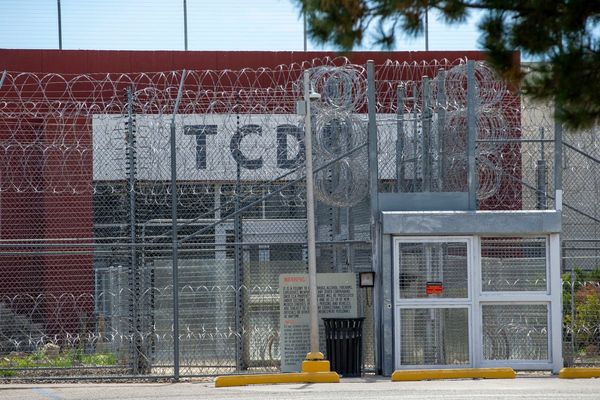

The construction of Fortress Britain is a gruesome foreshadow of a dystopian future. As things stand, asylum applications are not high by recent historical standards. In 2022, there were fewer than 75,000 claims for asylum; compare that with nearly 99,000 in 2000 or more than 103,000 in 2002.

Britain takes in a vanishingly small share of the world’s refugee population: rich countries, which account for nearly two-thirds of the global wealth, only host 26%, and Britain has a far lower rate of asylum claims than France or Germany. What has changed is the mode of arrival: more now arrive by sea, because most safe and legal routes have been eliminated. There may be fewer refugees coming here, but the optics of their arrival has been changed by government design, allowing the Tories to demonise a desperate human tide as an “invasion”.

The damage wreaked by global capitalism we know. But by also sending hundreds of billions of metric tonnes of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, humanity has made a serious error whose most serious consequences are yet to be felt. Those who will suffer the brunt of the climate catastrophe bear least responsibility: the world’s wealthiest 1% were to blame for more than twice as much carbon dioxide emissions as the poorest half between 1990 and 2015. Crudely put, many of the world’s poorest will be forced to flee their homes because of the actions of the world’s richest. The right claims there is a hard border between deserving “refugee” and undeserving “economic migrant”; in truth, it’s far more complicated than that, and the rise of the climate refugee will blur that distinction even further.

The wealthiest countries will respond by whipping up fear and bigotry against the climate refugees, and building ever greater walls to keep them out. A perverse irony is likely: many of the far-right parties who have opposed action to tackle the climate emergency may be the biggest political beneficiaries, stoking fears about those forced to abandon their homes for cynical electoral gain.

That many people will be forced to flee because of the climate emergency is beyond doubt. In 2018 alone, around 5 million people were displaced in Africa’s Sahel region – home to 10 nations – and droughts, floods and food insecurity driven by the climate crisis was partly to blame. Deadly heatwaves in the Indian subcontinent last year were found to have been made 30 times more likely because of the climate emergency, while floods in Pakistan – which research suggested were made 50% worse by rising temperatures – destroyed millions of acres of crops and left vast swathes of the country under water.

What happens when rising sea water begins to subsume low-lying Bangladesh – population 169 million – and the Maldives? With 2 billion humans lacking access to safe drinking water, what happens when changing weather patterns threaten freshwater stores? What happens when the production of staple crops is disrupted, sending food prices surging? What happens as droughts, floods and wildfires increasingly ravage already vulnerable populations? What, too, will be the consequences of the inevitable surge in armed conflicts provoked by growing competition for ever scarcer resources?

Well, the answer is straightforward: people will take the rational decision to flee. Based on current patterns, most will be internally displaced within their own countries, but a significant number will cross borders, mostly for neighbouring countries. Only a small proportion will make their way to the global north: but with far more fleeing their homes, that small proportion will represent far greater absolute numbers. Our rich nations will see the consequences of their own actions hurtling towards their shores, and they will spend vast resources to drive them back.

It may seem reminiscent of Elysium, a dystopian 2013 film in which the rich and powerful live in a vast space station orbiting a collapsing, impoverished, diseased Earth. There is a crucial difference, though: the global north will not be the exclusive home of the well-to-do, or even close. After all, growing panic over refugees serves to deflect popular anger away from domestic problems, such as poverty, collapsing public services and the housing crisis. The scapegoating of the world’s most vulnerable humans hurts the living standards of the poor at home.

The rulers of a declining, grotesquely unequal global north will claim legitimacy by promising to drive back the human tides. We may see a form of eco-fascism: far-right parties may stop denying the climate emergency as it becomes too obvious to wish away, but claim the catastrophe underlines the need to keep the rest of the world out. Fortress Britain is already here, built by Tory cruelty and legitimised by Labour cowardice. The decisions made by our political and economic elites threaten to tip much of the world into chaos – and make the dystopian nightmares of Hollywood films our lived reality.

Owen Jones is a Guardian columnist

Owen Jones will be in conversation with Ibram X Kendi, author of How To Be An Antiracist, at a Guardian Live online event on Tuesday 7 March. More information here

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a letter of up to 300 words to be considered for publication, email it to us at guardian.letters@theguardian.com