At the national Australia Day ceremony in 2021, Prime Minister Scott Morrison spoke of the contribution by frontline workers during the pandemic. He mentioned health workers, the defence forces, the police and farmers, as well as “the truck drivers, the wholesale and the retail workers keeping our supermarket shelves stocked”.

In his 2022 Australia Day speech only defence personnel and health workers got a mention – possibly due to the disappearing government support for retail and logistics workers during the Omicron wave.

With Omicron crippling supply chains and businesses being forced to shut due to lack of staff, eligibility rules for the last remaining COVID-related support payment (the Pandemic Leave Disaster Payment) have been tightened, and the payments available cut.

The definition “close contact” has been weakened and tens of thousands of workers have been made exempt from isolation protocols by now being classified as “essential”.

Many frontline workers – namely those on casual contracts – are facing the toughest circumstances since the the pandemic began.

With no right to guaranteed minimum hours, sick leave or the other entitlements, those employed as casual workers or as subcontractors are likely to lose income – either due to having to take time off to get tested or self-isolate, or because their workplace hasn’t got enough staff to stay open. There is also a much higher proportion of casual workers in the retail sector, than in the Australian workforce as a whole.

Our research on the effects of the pandemic on income and conditions for workers between March 2020 and September 2021 shows 55% of those working in retail, fast-food and distribution were forced to take time off work for COVID-related reasons – with a significant percentage losing income as a result.

During this time just 1% of retail workers were diagnosed with COVID-19, and the the financial support available included the lockdown-specific Covid-19 Disaster Payment.

Now, with infection rates running significantly higher – a quarter of Coles warehouse staff, for example, have been reported absent due to COVID-19 – there’s less support.

Casual retail workers thus face losing hours, being put at greater risk of contracting COVID-19, and dealing with abusive customers over mask, QR code and other requirements.

Read more: Content from confrontation: how the attention economy helps stoke aggression towards retail workers

What our survey showed

The purpose of our survey of nearly 1,160 retail, fast-food and distribution workers was to gauge how the pandemic had affected employment and income.

Polling company Ipsos conducted the survey in September 2021, during the peak of Sydney’s Delta wave (which sparked suburb-based lockdowns in mid-July 2021) and the start of Melbourne’s Delta wave (with the Andrews government declaring a lockdown on August 5, 2021).

The survey was nationally representative. About 61% of respondents were women, 44% were younger than 30, and 19% were from a non-English-speaking background. About 39% were permanent full-time, 21% permanent part-time and 38% casuals (45% of women were casual, compared with 22% of men).

Because it was nationally representative, about 40% respondents were not in an lockdown area (NSW, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory) at the time of the survey. This make the results even more stark compared with now.

From March 2020 to September 2021, 55% of retail, fast food and distribution workers had to take time off for a COVID-19 related reason:

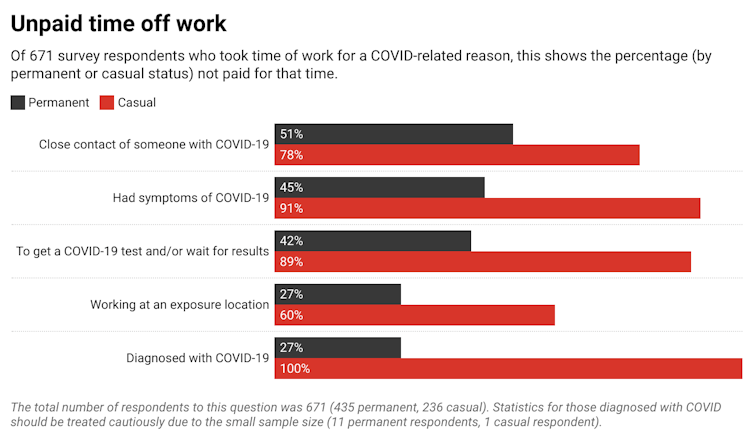

- 1% did so due to having COVID-19. Of these, about a third said they took unpaid leave.

- 7% did so due to being a close contact of someone with COVID-19. Of these, 51% of permanent workers and 78% of casuals took unpaid leave.

- 11% took time off because they had COVID-19 symptoms. Of these, 45% of permanent workers and 91% of casuals took unpaid leave.

- 10% were absent due to working at an exposure location. Of these, 27% of permanent workers and 60% of casuals took unpaid leave.

- 30% took time off because they had to take a COVID-19 test and isolate while waiting for a result. Of these, 42% of permanent workers and 89% of casuals took unpaid leave.

Clearly while very few workers were actually sick with COVID-19, it had a significant affect on livelihoods. This a key point to reflect on now more workers have COVID-19 and an even larger number are (or should be) isolating.

Short shift for precarious work

At the time of our survey the risks of catching COVID-19 were relatively small, even for essential frontline workers.

Omicron has substantially increased that risk – along with the risk of losing work hours.

Registering a positive result is the only way ill, casually employed workers can access extra support when they aren’t able to work. But getting a test – and results has been difficult, with workers in NSW and Victoria only been able to officially register positive RAT results since January 10.

The Pandemic Leave Disaster Payment is still available to those who don’t qualify for employer-paid leave. But to qualify you must be directed to isolate and stay at home due to having tested positive or been in close contact with someone with COVID-19.

Read more: What a disaster: federal government slashes COVID payment when people need it most

You also only qualify for the full $750 a week (for two weeks) if you lose 20 hours or more of paid work a week. If you lose 8-19 hours, you get $450 a week. If you lose less than eight hours, you get nothing.

This highlights the precarious and unsustainable position of Australians employed on casual contracts, especially those in the retail, fast food and distribution sector. Many unwell or at-risk precarious workers are likely to have gone without income while they struggle to get access to tests or lose paid work for other reasons.

Ariadne Vromen currently receives funding from the Australian Research Council for research into gender equality and the future of work.

Meraiah Foley is a Chief Investigator on two grants funded by the Australian Research Council. She has also received research funding from the Australia New Zealand School of Government.

Rae Cooper currently receives funding from the Australian Research Council for research into gender equality and the future of work and as an ARC Future Fellow.

Briony Lipton and Serrin Rutledge-Prior do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.