Loaded with drugs, the buses left Iguala in southern Mexico every week bound for Chicago.

Secret compartments made detection at the border almost impossible.

At warehouses in Aurora and Batavia, the heroin was unloaded, then distributed around Chicago and across the country.

Over a year, starting in July 2013, the Guerreros Unidos Mexican drug cartel imported about 2,000 kilograms of heroin to Chicago, authorities say. Millions of dollars were sent back to Mexico in the same compartments.

“When we came to the realization as to the volume of heroin that they were trafficking, the significance really hit home to us,” former U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agent Mark Giuffre says. “Practically every week, shipments were coming in on these buses.”

Compared to more powerful organized crime groups like the Sinaloa cartel, at the time led by now-imprisoned Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera, Guerreros Unidos was just a fledgling gang.

“They were up-and-comers,” says Jack Riley, who headed the agency’s Chicago office and became the No. 2 official with the DEA, helping make the case against El Chapo.

Though smaller than the Sinaloa cartel, Guerreros Unidos helped fuel Chicago’s growing appetite for heroin, bringing in quantities equal to tens of millions of doses on tour buses, authorities say.

“The GU’s heroin operations in the region were operating at a very high capacity at the very time heroin-related emergency room treatments and overdose deaths were rapidly increasing here,” Giuffre says.

What the cartel lacked in power and reputation, it compensated for in ingenuity. Its tactics included bribing Mexican police and military officials and installing hiding places on the buses so complex that, when U.S. authorities eventually seized one and took it apart, they couldn’t find any trace of the stash.

“Guerreros Unidos were under the radar of law enforcement because big money was focused on El Chapo,” Giuffre says. “We were blind to what was happening.”

Veracruz Tampico Ometepec Puebla Cuernavaca Mexico

City León Guadalajara Aguascalientes San Luis Potosí Querétaro

Mexico Pacific

Ocean

The cartel’s anonymity didn’t last for long. In the fall of 2014, Guerreros Unidos became infamous around the world for perpetrating one of the most heinous crimes in modern Mexican history: the disappearance and presumed massacre of 43 college students in Iguala in the state of Guerrero. The remains of only three of the students have been found.

The cartel’s reputed leaders — including brothers and former Chicago pizza deliverymen Adan Casarrubias Salgado, known as El Tomate, and the late Mario Casarrubias Salgado, nicknamed El Sapo Guapo, or the Handsome Toad — became suspects in that atrocity, which continues to shake the foundations of Mexican society.

Even now, nearly nine years later, the case remains shrouded in mystery. At the end of July, international investigators presented a final report that accused the Mexican army of stonewalling their investigation.

To get a better sense of what happened, and the role of Guerreros Unidos, the Chicago Sun-Times examined hundreds of pages of documents in the United States and Mexico, interviewed current and former law enforcement officers on both sides of the border and visited key places where the cartel operated in Chicago and Mexico.

A raid in Ravenswood

A key piece of the story is how the DEA took down the cartel’s lucrative Chicago operation. That begins on the Northwest Side.

During a money-laundering investigation in August 2013, Giuffre detained a cartel courier carrying $200,000. That courier, arrested in a parking lot, gave up details of the operation.

The DEA raided his gray clapboard house on Winnemac Avenue in Ravenswood and seized another $231,000 plus 12 kilograms of heroin and 9 kilos of cocaine. Agents also arrested the courier’s boyfriend, an Army veteran who went on to become the DEA’s most important informant in the case.

“It became clear early on that this was not a money-laundering cell,” Giuffre says. “This was a heroin-trafficking cell that happened to launder some of its own money.”

The DEA launched a surveillance operation. It tapped cartel members’ phones, intercepting text messages, and followed them to cash drops and back-alley drug deals. Spanish translators helped decipher the codes used by the traffickers.

A hierarchy emerged.

The Casarrubias brothers were leaders of the cartel in Mexico, authorities say.

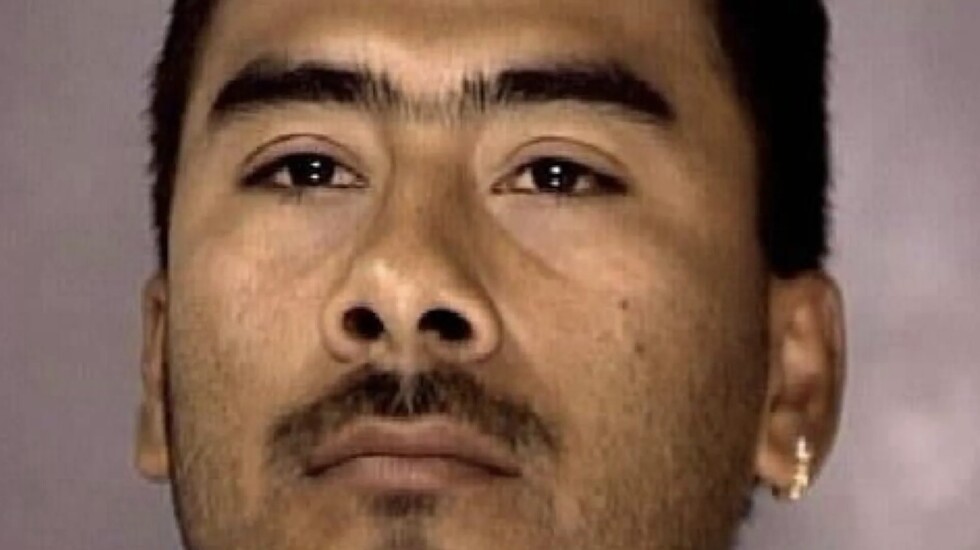

And running the show in Chicago was Pablo Vega Cuevas, whose nickname among traffickers was “Transformer.” Playing off the movies, the DEA’s investigation was dubbed Operation Megatron.

Though they were born in Mexico, Mario Casarrubias and Adan Casarrubias lived for years in Chicago. They worked at Mama Luna’s pizzeria on Fullerton Avenue in Belmont Cragin on the Northwest Side. Workers at the restaurant say they still remember them handling deliveries.

The siblings also got in trouble.

Adan Casarrubias was charged in 1999 with involvement in drug smuggling.

U.S. authorities seized more than 5,500 pounds of marijuana and 48 pounds of cocaine they said had been hidden in a load of cookies on a Chicago-bound tractor-trailer in Texas — a shipment valued at $7.8 million. He was taken into custody in Chicago and sent to Texas, where he pleaded guilty to money-laundering charges and got a 21-month prison sentence.

His brother had his own run-ins with the law. Mario Casarrubias was arrested in 2002, accused of stealing stereo equipment from a car in Lincoln Park. He pleaded guilty and got probation. He was arrested again in 2004 after the police said he shot at a car five times, and the cops seized a .357-caliber Magnum revolver.

“People always try to fight me,” he said when asked why he had the gun, according to a police report.

He pleaded guilty to gun possession and spent nine months in the Illinois Department of Corrections.

Guerrero: a ‘criminal death spiral’

Eventually, the brothers moved back to Mexico and graduated to the major leagues of organized crime, according to Mexican authorities, who say Mario Casarrubias began working as a bodyguard for the Beltran-Leyva cartel, a splinter group of El Chapo’s Sinaloa cartel.

But, after the killing of cartel kingpin Arturo Beltran-Leyva in 2009, the Beltran-Leyva group began to fall apart. It fragmented into smaller gangs that fought each other over territory.

That set off a wave of violence, particularly in southern Guerrero state, which had become Ground Zero for the heroin trade.

A crackdown on the over-prescribing of painkillers like OxyContin in the United States in the late-2000s created a surge in demand for illegal opioids from people suddenly cut off from their pain pills. Mexican cartels soon filled the gap, ramping up their production and trafficking of heroin.

Guerrero’s humid climate and rugged hillsides, its impoverished farmers eager for extra income and its entrenched government corruption made it ideal for growing the poppies used to produce heroin.

“You had the perfect circumstances within Guerrero,” says Paul Craine, former regional director of the DEA in Mexico. “In a very, very short period of time, you have a lot of different things happening that send the state of Guerrero into this criminal death spiral.”

Among the groups that rose from the remnants of the Beltran-Leyva organization and gained a foothold in Guerrero’s burgeoning heroin trade was the Guerreros Unidos cartel.

Authorities say The Handsome Toad became its leader.

Meanwhile, in the United States, court documents show, the Vega brothers were making their own way into the underworld. Pablo and Marco Vega were born in Mexico but grew up in Aurora. The beige house where they lived still sports a metal crest with the Cuevas name: “God bless our family,” it reads in Spanish.

Years before he was accused of being a trafficker, Pablo Vega held blue-collar jobs, according to court records. In his 20s, he worked at a Yorkville tool factory and at a brake-shoe factory in West Chicago.

The brothers never graduated from high school and got into plenty of trouble with the law.

Marco Vega had a particularly violent streak. In 1994, at 15, he was found guilty of beating another teenager with a billy club, leaving a one-inch gash on his head, as his brother held the boy down, according to police and court records.

Two years later, Marco Vega and four other teenagers attacked two young men at an Aurora restaurant, according to police. He was found guilty of aggravated battery and sent to a youth facility.

In 1999, Marco Vega, then 20, was arrested after police seized 12 pounds of marijuana and $26,000 from a home in Aurora. He forfeited the money. But his lawyer successfully argued that a judge should dismiss the criminal case, saying his client didn’t live there, records show.

Marco Vega was back in court in 2001 for beating up his girlfriend. He pleaded guilty to domestic battery and domestic violence.

Months later, according to court records, he “threw her into a wall, pinned her to the floor and held his hand over her mouth so she could not breathe.” After violating his probation, he spent five months behind bars.

In 2009, Marco Vega was deported to Mexico, court records show.

Switching cartel sides

According to testimony from a former cartel member obtained by the Sun-Times, Marco Vega began working for Los Rojos, another group that splintered from the Beltran-Leyva cartel and became one of Guerreros Unidos’ biggest rivals. He was sending shipments of cocaine and methamphetamine every two weeks on passenger buses from Apaxtla in Guerrero to Chicago, Houston and Atlanta, the cartel member testified.

Then, in 2010, Marco Vega, nicknamed “Minicooper,” switched sides, joining the Casarrubias clan and becoming one of the top lieutenants in Guerreros Unidos.

According to testimony from another former cartel member, referred to in records as “Juan” by Mexican authorities, Marco Vega would buy large quantities of the opium gum produced by farmers in the hills of Guerrero. The gum was cooked into heroin and shipped to the United States.

His brother was put in charge of distributing the drug across Chicago and to Oklahoma, Atlanta, South Carolina, New Jersey and Los Angeles, according to Juan’s testimony.

With Pablo Vega set up in the Chicago area and the Casarrubias brothers working in Iguala and surrounding towns, the Guerreros Unidos operation was in full swing, relying on Mexican police, military and local politicians on the take — as well as the cartel’s ingenious mechanism for hiding heroin on buses.

In the summer of 2013, things started going awry. First, there was the seizure of nearly half a million dollars in drug proceeds by Giuffre and his DEA team, which the cartel seemed to take in stride.

Then, in March 2014, Marco Vega took a trip on a lake in Mexico to celebrate his wife’s birthday, according to a law enforcement source. When his wife fell into the water, he and his bodyguard jumped in to save her, but Vega never came back up, the source says. According to the source, there has been speculation that Vega’s death might have been a hit.

The following month, Mexican authorities arrested Mario Casarrubias. They said he was “one of the main traffickers of drugs to Chicago,” transporting them on fruit trucks and passenger buses.

Another brother, Sidronio Casarrubias Salgado, took charge of Guerreros Unidos, with Pablo Vega becoming second-in-command, according to Juan, the former cartel member.

In July 2014, a high-level cartel member, Gonzalo “The Uruguayan” Souza Neves, was arrested by the Mexican army along with an associate. Authorities seized 24 kilograms of drugs and $250,000 in cash, according to the Mexican government.

In a written statement, Mexican authorities said Souza Neves oversaw drug trafficking via “hidden compartments” on vehicles, particularly buses, to Chicago.

The same month, a chance encounter almost blew up the cartel’s whole operation — and the DEA’s investigation. Pablo Vega and another cartel member were stopped by police in Webb County, Texas, for a traffic violation. Texas police seized $21,000, some sewn into the traffickers’ waistbands or hidden in their shoes. The two were released without charges. But Vega was spooked.

“Move the truck,” he texted a cartel member back in Chicago, referring to a vehicle used to transport drugs, according to a criminal complaint. “Put it away. We got f----- over here.”

Vega texted his sister, instructing her to move two safes with drug money out of his home in Aurora. He also instructed his associates to remove cash and drugs from one of the warehouses.

For months, the operation went cold.

Terror in Iguala

Despite its lucrative business, the Guerreros Unidos cartel might have gone down in history as just one more in a long line of mid-sized Mexican drug-trafficking groups.

On the night of Sept. 26, 2014, everything changed.

About 100 students from a teachers’ college in Guerrero commandeered several buses in Iguala, planning to use them to ride to a protest. For years, the practice of hijacking buses had mostly been tolerated by authorities and bus companies.

That night, though, police officers and other gunmen in Iguala began firing at the unarmed students. Several were wounded. Dozens were taken away in police vehicles.

By dawn, six people were dead, and 43 students had vanished.

Exactly what happened is still unclear. According to Juan, the government informant, there was a war going on among rival gangs for control of the area at the time of the attack.

Text messages intercepted by the DEA and published in a report by international investigators last year suggest that Guerreros Unidos might have believed an opposing group entered Iguala along with the students.

Independent researchers on both sides of the border believe the students’ hijacking of buses, one of which could have been carrying drugs bound for Chicago, was likely a motive for the attack.

“There is no direct evidence that those buses commandeered had concealed shipments of heroin or cash,” Giuffre says. “But there is a mountain of evidence that Guerreros Unidos controlled passenger buses with concealed compartments that moved massive amounts of heroin from Guerrero to Chicago.”

Who gave the order to attack the students also remains unclear.

Mario Casarrubias was in jail at the time of the attacks. But Mexican court documents suggest that the order to “f--- them up” came from him, Adan Casarrubias and two of their other brothers.

According to Juan’s testimony, Adan Casarrubias took part in “coordinating, directing and ordering what happened to the students.”

The students’ abduction — and their likely massacre by the cartel — was met with outrage, sparking protests across Mexico and condemnation from international human rights organizations.

The government of former President Enrique Peña Nieto vowed to solve the crime. But what followed, according to the team of international investigators, was a cover-up, with suspects tortured into giving false confessions and evidence planted or manipulated by Mexican government officials.

The government blamed the disappearances solely on Guerreros Unidos and local cops, absolving federal forces of blame for the attack and for involvement in the drug trade.

And the government’s initial probes obscured the Guerreros Unidos’ heroin-trafficking and use of buses as a possible motive in the attack on the students — despite ample evidence of the drug operation.

“We know that every Friday a bus left that bus station bound for Chicago,” says Carlos Beristain, one of the international investigators. “Why doesn’t it appear in any reports?”

The Mexican attorney general’s office at the time tried to close the case, “hiding the responsibilities of different forces and institutions of the state,” the investigators said in a report in March.

According to the investigators, the Mexican military had spies infiltrated among the students and had real-time intelligence on the attack as it took place; soldiers and federal police were present at the times and places where the students were attacked and abducted.

Despite this, the investigators wrote, “No action was taken at the time to protect or rescue or search for the young men.”

‘Going to cost us the business’

Back in Chicago, the mass killing became a source of concern.

Pablo Vega texted colleagues in Mexico that the students’ abduction and the chaos that followed “is going to cost us the business,” according to intercepted messages published in Mexican media.

Still, despite the arrests of several cartel members, including Sidronio Casarrubias in October 2014, the Guerreros Unidos operation was soon up and running in the United States.

At the end of that month, Vega and his associates were again distributing heroin in Chicago, according to court documents.

Giuffre and his DEA team were under increasing pressure from the U.S. attorney’s office in Chicago to take down the cartel. By December, they were ready to move.

But, on the morning they were set to make arrests, Giuffre and his colleagues realized that Vega and his brother-in-law Alex Figueroa were on the move, heading toward the Mexico border.

“He booked it,” Giuffre says.

By tracking Vega’s phone, the DEA pinpointed his location in Oklahoma. On Dec. 9, 2014, police in Oklahoma arrested Vega and Figueroa. Three other cartel members were arrested in the Chicago area, and police and DEA agents seized cars and raided homes and businesses in Aurora, Chicago and Rockford.

At least eight Guerreros Unidos associates have pleaded guilty to federal drug-trafficking charges in Chicago, including Pablo Vega. Six have served time in prison and have been released from custody. Vega is set to be sentenced this month.

Adan Casarrubias and his lawyer didn’t respond to requests for comment. Vega’s attorney would not comment.

The state of the cartel today

Today, the Guerreros Unidos cartel has largely ceased to exist in Chicago, according to law enforcement sources.

In Mexico, the group continues to function but has split into two, according to court filings.

The remaining Guerreros Unidos faction is led by the mother of the Casarrubias siblings, according to court records in Mexico.

In 2017, Mario Casarrubias was sentenced to 10 years in prison for possession of drugs and firearms, according to Mexican media reports. The Handsome Toad died of the coronavirus in 2021 before he could serve out his sentence.

Announcing his death, the Mexican government’s truth commission in the Iguala case said he was “linked to the disappearance of the 43 students.”

Adan Casarrubias is facing federal charges in Chicago of conspiracy, drug-trafficking and money-laundering.

In a court filing, he unsuccessfully sought a compassionate release, saying he’d been a victim of torture in Mexico, including “suffocation with plastic bags,” at the hands of government authorities.

In a separate filing, he denied being a Guerreros Unidos leader, saying his former job as a pizza deliveryman “does not exactly qualify him for the role of cartel kingpin.”

He also said he has “family roots” in Chicago, noting that his son and daughter attend colleges in Illinois. He also described “friendships dating back to his Mama Luna’s Pizzeria delivery days.”

Adan Casarrubias remains in federal custody, awaiting trial.

In Mexico, after years of missteps and cover ups in the investigation of the 43 disappeared students, the government has recently taken some action.

Over the past several weeks, 10 soldiers were arrested for possible involvement. Four other military officers are awaiting trial.

Yet more than eight years after the students disappeared, not a single person has been convicted of that crime in Mexico.

The international investigators on the case have now left Mexico for good, leaving little hope of ever knowing what really happened to the students.

“There’s no way you can get to the truth,” Giuffre says. “The glass has been shattered.”

Frank Main is a Chicago Sun-Times reporter. Oscar Lopez is a freelance reporter based in Mexico City. His reporting for this story was supported by The Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.