John lays out two small bags in front of him, each of them containing a white powder. He holds one up to a light and taps it to examine the contents.

“This is definitely fentanyl,” he says. “See the white colour? Heroin is not that colour.”

He drops the powder in a small pot of water and waits for the bumps to dissolve. He loads his needle, pulling the liquid through a filter, and pauses. It’s a ritual he has performed countless times before, but something has been different lately. Now, he has helpers. As he readies his shot, a trained staff member comes over to help him tie a tourniquet on his arm. There are several other trained staffers on hand, too. They watch over him carefully as he injects the drug into his vein.

What is an everyday act for John is a bold experiment for the city of New York, and indeed for the country. This small room at the back of a former needle exchange in east Harlem is the nation’s first sanctioned supervised consumption site — a place where drug users can consume safely and without fear of arrest.

“After you’re done using, say you’re really out of it, they will put you in a chair, they will feed you, they will put oxygen in you. They are great here, very understanding. Even when people freak out from the stimulants or the hallucinations,” says John, 29.

Users are provided with clean needles, sanitising equipment, filters, saline solution, a private cubicle and even a warm towel to help find a vein. If they overdose, those trained staff are there to administer medication to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

“With my own eyes I’ve seen them save 12 people,” says John. “This environment is so much safer. I’ve never had an overdose, but if I did, then this would be the place to be.”

The need for urgent action to address the opioid crisis was underlined by record overdoses in the US in recent years, a trend which worsened during the pandemic. More than 100,000 people died from an overdose in the 12 months leading up to April 2021 — mostly caused by the rise in the use and accidental use of the synthetic drug fentanyl. Over 2,000 of them happened in New York. This centre and its partner site in Washington Heights, both former needle exchanges, aim to save lives by being there at the moment it counts, in the first seconds an overdose occurs. OnPoint NYC, the nonprofit that runs the two sites, say they have averted 124 overdoses since opening on 30 November, far beyond their estimates.

That these centres exist at all is the result of a years-long effort by campaigners on the frontline of the drug crisis, who urged lawmakers to study and replicate the success of similar programmes in Europe and Canada. Bill de Blasio authorised the sites in one of his last acts as mayor of New York City, calling them “a safe and effective way to address the opioid crisis.” The city’s new mayor, Eric Adams, has also expressed his support for the programme.

Sam Rivera, the executive director of OnPoint NYC, remembers those decades of failure well. He has spent 30 years working in the fields of drug addiction and HIV AIDS prevention. For years, he says, the public perception of drug users has impacted policy for dealing with the drug crisis.

“The way people have seen drug users is disposable: get rid of them, put them in prison. I think a lot of that is a fear of the unknown,” he says.

“There’s been a relay race for many, many years to get to this point. Many colleagues I’ve lost and I love, friends and family I’ve lost and I love, who have been fighting for this kind of intervention because they know it works. They know we’ll keep them alive.

“It sounds so radical, but radical is what works, right?”

The sites have faced some opposition, too. Some local residents have expressed concern that the centre would bring drug users from across the city to their neighbourhood. Reverend Al Sharpton also expressed his opposition shortly after the site opened its doors: “We are compassionate and want to help all the vulnerable population in New York City, however, we cannot be complacent regarding the decades-long process of systemic racism that has oversaturated our community,” he said in a statement.

The two sites operate in something of a legal grey area: Federal law does not yet allow for legal supervised injection sites. The Justice Department under Donald Trump sued to stop a supervised injection facility opening in Philadelphia. But city officials have sanctioned the site and are reportedly working with the Biden administration about a way forward.

On 7 February, the Associated Press reported that the DOJ was now “evaluating” the facilities and may be open to allowing them to operate.

Mr Rivera admits the safe injection programmes have faced significant opposition over the years, but says times have changed. He credits the right administration at the right time, and the right team. His colleague, Kailin See, senior director at OnPoint NYC, was a key part of that effort. She came to the centre after previously working in the only other legal supervised injection site in North America, in Vancouver, Canada.

Her experience taught her that providing a safe place for drug users was only part of the story.

“There’s nothing that I see in any of the systems, treatment, recovery, housing, education, employment, that demonstrates to me any real will to welcome [drug users] back into society. And so they stay suffering,” she says. “Our sites acknowledge that their lives have value and the entire service continuum that we’re trying to build acknowledges that their lives have value.”

As part of that effort, the centre offers a range of services beyond the supervised injection room. On one floor of the building is a dimly-lit “holistic services room,” where people can receive massages, ear acupuncture, and reiki. Downstairs people visiting the centre can get a hot meal, visit a pharmacy or sit in a garden out back. There is a medical clinic on site where people can receive treatment and harm reduction healthcare.

“Anytime we refer one of our people somewhere, we have a system breakdown,” says Ms See. “Nobody houses active drug users, the hospital doesn’t want them, nobody employs them, they could lose their kids. So we’re trying to rebuild the system ourselves.

“If someone is interested in treatment there, it’s literally a two-step walk over here to get medical care. There’s no stigmatising. No one’s gonna treat you terribly. You can have some food and then you can pick up your prescription here,” she adds.

When users visit OnPoint NYC they first check in to a waiting room at the front of the building. On the day The Independent visits it is loud and bustling. Some people are eating birthday cake, others are eating a warm meal. Some are waiting to use and some already have.

A set of doors at the back of that room leads into the overdose prevention room. It is lined with small cubicles on each side with mirrors in front of them. Those mirrors have a dual purpose: most drug users are used to taking drugs in unsafe places, so it helps to see what is around them. It also acts as a safety measure so they can see the effect of the drugs they are taking on themselves. Beyond the cubicles are two smoking rooms, for people to take drugs that need to be inhaled, into which music is played.

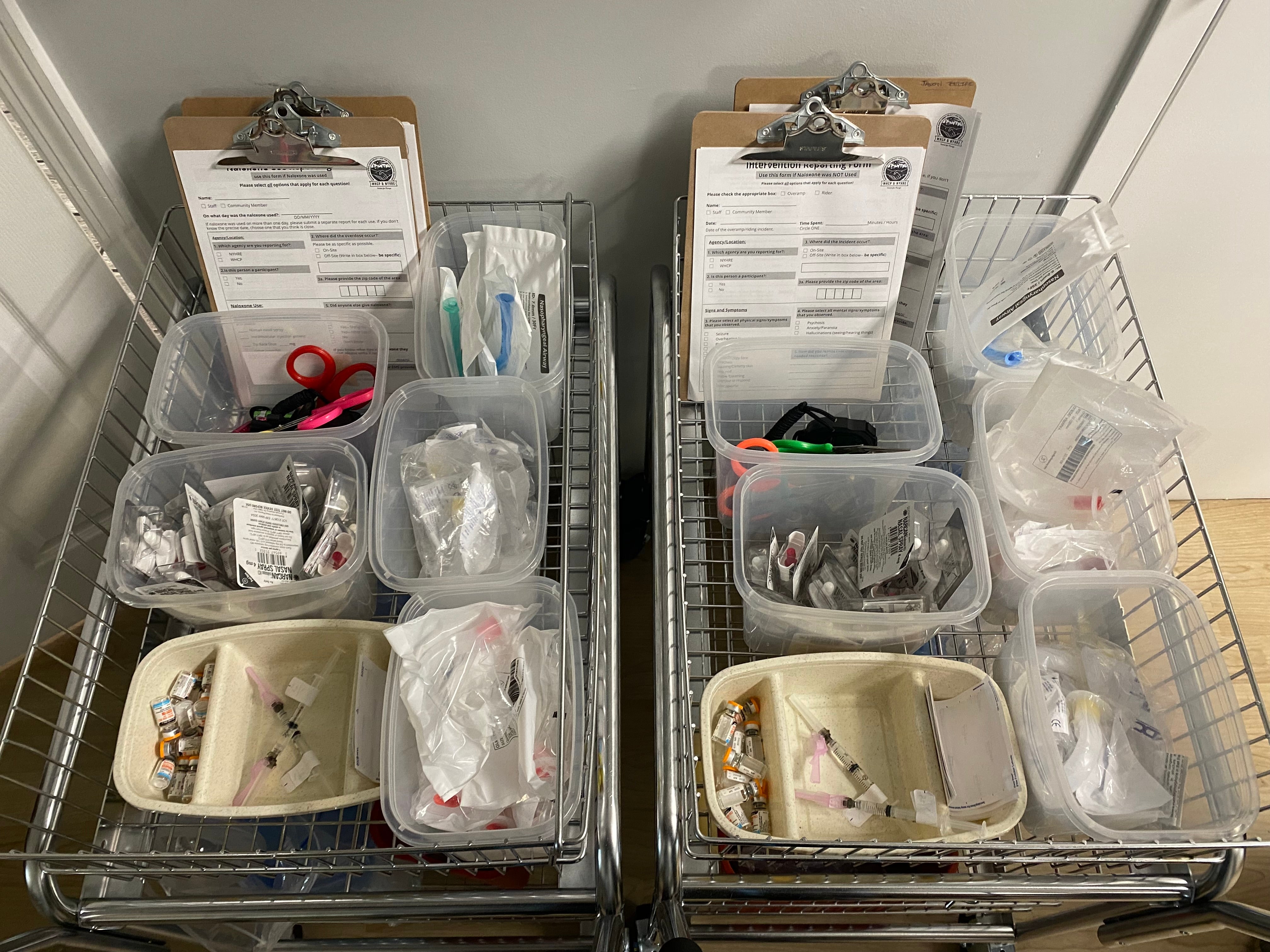

In the centre of the main room sits a cart on wheels with a tray containing everything someone might need to take their drugs safely. There are needles, band-aids, cookers, ties to help find a vein, straws to take drugs through the nose, gauzes and alcohol wipes. Alongside it there is an “overdose cart” that contains medications to intervene in an overdose, such as Naloxone.

Ms See says that many users have been reluctant to use supervised injection sites where Naloxone is used heavily because it immediately killed their high and made them extremely sick. Being there at the moment an overdose occurs allows them to use different methods.

“What it did was make people really nervous to come and use our unsanctioned programme in case we gave them this and made them really sick. So now, because we’re there the very second the overdose occurs, we’re now microdosing with injectable Naloxone,” she says. “The objective here is to prevent the loss of consciousness. So the best practice is to intervene, even in a very heavy fentanyl-involved overdose, with only oxygen. You can only do that successfully if you’re there at onset. And that’s why these sites are so effective.”

The staff in this room have been trained to treat overdoses at the same level as a nurse. Most of the time, though, they help the users with anything they might need to take their drugs safely. That can include simple advice and education, or offering pathways to rehabilitation and treatment if users ask.

“I’m very fond of saying the least interesting thing that happens in this room is the actual drug consumption,” says Ms See.

In the short term, staff here are happy with the numbers they are seeing. In the long term, they hope their programme will spark a nationwide change in drug policy.

“For me, the most exciting thing is that it’s working,” says Mr Rivera. “It’s really about keeping people alive. And if they stay alive, then they have an opportunity to change their lives and improve in a variety of ways. Everybody’s focusing on the fact that they’re using drugs, but their drug use is one element of who they are. Many of our people need jobs and housing, they wanna reunite with family. We can help them with that.

“So the service is much bigger than what we’re able to capture in data. It’s not just those numbers. It’s bigger than that.”