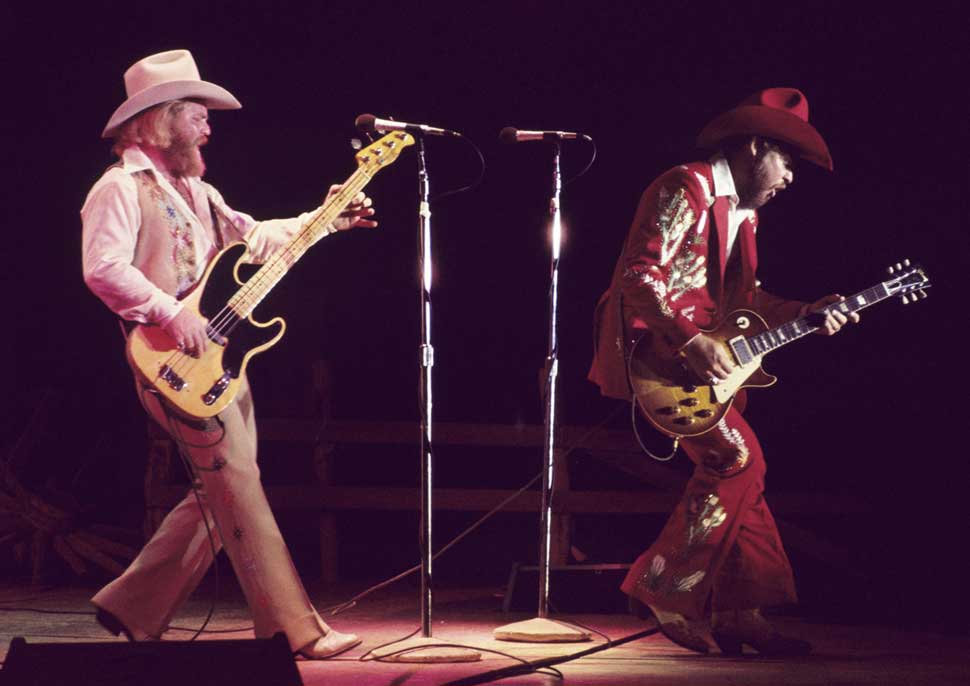

In the 47 years since ZZ Top set off on their Worldwide Texas Tour, their outrageously over-the-top trek has passed into legend.

The band’s mission was to “bring Texas to the people”, and they certainly succeeded in that: as well as a 35-ton stage in the shape of the Lone Star State, they also took along a veritable menagerie of Texan critters including a buffalo, a Longhorn steer, several venomous rattlesnakes, some tarantulas, and six vultures all called Oscar. But even the band couldn’t have foreseen the original 33-date tour mutating into a record-breaking 18-month behemoth.

Billy Gibbons (guitar/vocals, ZZ Top): That was the start of who could create a production to outdo the previous. It seemed like every week some band would have a wider stage, more lighting, more props.

Ralph Fisher (animal wrangler): I was a country and western fan, a rodeo bullfighter and comedy entertainer at an indoor rodeo near Houston. About a year before the tour started, someone knocked on my dressing room door and told me that Bill Ham, the manager of ZZ Top, would like to interview me. I said: “ZZ what?” I had no idea who they were.

Jay Boy Adams (singer/guitarist): I had known ZZ Top since 1970, and I’d worked with them as a musician and as a backline tech. As well as being their manager, Bill Ham was also the architect of the Worldwide Texas Tour.

Ralph Fisher: When I met Bill Ham two days later, the first thing he asked me was: “Can you train a buffalo?” I said: “Yes.” And he said: “You’re hired.” Bill wanted a real live buffalo on stage, and a live Texas Longhorn. So I procured both. I rented a scissor lift so I could train them to walk up a ramp and get on a platform.

For months, we played loud rock music to them on a timer so it would come off and on during the night, along with a light show. I popped firecrackers near them, waved flags, anything to simulate what might happen in a concert. I already owned several other animals for my rodeo show, including the buzzards, so it naturally fell to me to acquire all of the animals for the tour.

Micael Priest (poster artist, assistant to set designer Bill Narum): ZZ Top had used my friend Bill Narum as their album cover designer for several years. Five days before the tour started, Bill called me and said he was designing a stage for the band, but they were running late and could I help him. They’d rented the Houston Astrodome Arena for rehearsals and to build the sets and paint the tour trucks.

Dusty Hill (bass/vocals, ZZ Top): There were six or eight semi-tractor trailers to carry the gear. They were painted with a panoramic desert scene, and they had to travel down the highway in a certain order so the scene went from one to another.

Micael Priest: The backdrop Bill designed was made of nine fabric frames, each 20-feet high and 30-feet long. Bill painted it to be a landscape of Santa Elena Canyon in Big Bend National Park, on the Rio Grande.

Jay Boy Adams: Bill Narum also constructed the Texas-shaped stage. He had it set at a six-degree angle so that people could clearly see the shape.

Billy Gibbons: The angle of the stage required some careful realigning of one’s tiptoeing techniques. Going down forward or backing up was okay, but the sideways movements, when the stage was tilted, you don’t want to twist your ankle.

Micael Priest: Bill Ham’s management company, Lone Wolf, had a logo of a wolf howling, silhouetted by a full moon. One of my first jobs was to paint a full moon on plywood. The idea was to train a wolf to sit in front of it, throw its head back and howl. Of course, you can’t train a wolf. So they got a little German shepherd dog instead, and the wrangler tried to teach it what to do. So, while we were painting, the wrangler was poking this dog under the chin with a bent-out coat hanger, and howling at him. That little dog was so eager to please, but he could not for the life of him figure out what this man wanted him to do.

Elvin Bishop (blues guitarist/singer): The tour started on May 29, 1976 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. I was one of the support acts on the first date. It was me, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Point Blank.

Paula Helene (props manager and wife of Bill Narum): After the warm-up acts finished, the Texas-shaped stage had to be laid down and decorated with fibreglass boulders, cactus plants, cow skulls, every kind of Texan paraphernalia. Then, while the stage was in complete darkness, I had to push this plexiglass pyramid full of rattlesnakes down to the bottom tip of Texas, then try to get off stage without bumping into any of the band as they came on.

Billy Gibbons: The animal rights groups were always present to make sure that these critters were being taken proper care of.

Ralph Fisher: Meanwhile, also in pitch dark, me and my helper had walked the Longhorn and the buffalo up the ramps, on to the scissor-lift platforms on either side of the stage and raised them up maybe 25 feet above the band.

Micael Priest: My full moon sat in the middle of the darkened stage. The plan was that a spotlight would pick out the dog howling, and Billy Gibbons would pick up that note to go into the first number. Right on cue, the dog trotted out, sat down and threw his head back. But he never did learn how to howl, so the howling was on a tape.

At that moment, the lights would come up for a couple of seconds, and then dim right back down, the sun would rise above Santa Elena Canyon, and it was spectacular to behold. Then Billy changed to another note which caused one of the vultures to hunch up, unfold his wings and flap them. And, sure as hell, the other three buzzards picked that up from him. It was astounding to see.

Billy Gibbons: We’d look up and think, “What’d happen if these critters got spooked and decided to take a flying leap?” There was every chance that they would make their way down to where we were standing. That was a little disturbing.

Ralph Fisher: It looked beautiful, so when the spotlights hit the animals up in the air the people went crazy. For about 30 seconds the lights stayed on them, before switching to the band in the middle of the stage doing their first tune.

Billy Gibbons: One evening in Richmond [June 3, 1976], this one rather sizeable turkey buzzard decided to take flight. He was making circles around the dome of the arena. And Ralph Fisher came out. He had trained this buzzard to look for a white hat and land on his head. But in our audience at the time there were a lot of white hats.

And this buzzard was swooping and circling. He didn’t know which white hat to land on. Finally we had to stop playing, and Ralph came out in the spotlight and whistled to the bird to land on his head. It made the rest of the evening rather challenging. How do you outdo a bird that knows how to land on a guy’s hat?

Dusty Hill: There was six buzzards, all named Oscar – 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 – and mine didn’t like me. Buzzards are shitty birds. I walked back near him one day and he tried to throw up on me.

Ralph Fisher: The rattlesnakes were our most dangerous animals, so we’d always make a spectacle of putting them in and out of their cage. We’d make sure one of them would escape, then we’d make a big show of recapturing it, because it made for good publicity. The headlines next day would be: ‘Rattlesnake escapes at ZZ Top concert.’

Micael Priest: One problem was that they couldn’t transport the snakes in the cattle trailer because it upset the Longhorn and the buffalo. So the head of security bought a long steel toolbox, drilled holes in both ends, and stuck biohazard stickers all over it. He then put the snakes inside. He’d fly from show to show carrying this case, so people were not inclined to mess with him. But the air conditioning didn’t always work, so the snakes would occasionally overheat, get irritated and begin to rattle. To cover it up, he would make loud, wet, farting noises with his mouth to keep everybody at bay.

Paula Helene: Bill Ham ruled with an iron fist – the band, the crew, everybody. He had rules for everything. Didn’t even allow the band to have beer. After the show, they would collect a bunch of women from the audience, invite them backstage to meet the band, shoot a bunch of photos with them, and then the band was taken away, confined to their hotel rooms, and the girls were standing there amazed. Ham didn’t want them staying up too late, partying too hard, whatever.

Micael Priest: Shortly after the show in Atlanta [June 5, 1976], they discovered someone was bootlegging all of their tour merchandise. He was travelling with a silk-screen printing machine in the back of his car and making up T-shirts every day, until they caught him. Bill Ham got this guy by the scruff of the neck and they took him into a side room, and there was quite a ruckus. Then it got real quiet, and Bill appeared at the door, all smiles, with his arm around the guy’s shoulder, and he says: “Ladies and gentlemen, I want you to meet our new head of merchandising.”

Rich Engler (concert promoter): I promoted the show at Three Rivers Stadium, the home of the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team [June 12, 1976]. Aerosmith were supporting. Their management demanded their own dressing rooms, which was not possible because ZZ Top had taken over everything. So I told them we’d build a special area out back and each one would get his own Winnebago, plus a jacuzzi, a barbecue and girls.

But there were problems out front. You had ZZ Top, beer drinkers and hellraisers, put together with a hair band, and the chemistry did not work for that audience. Aerosmith faced a barrage of beer bottles, cans and fireworks. To make things worse, halfway through their set the power went out. It turned out a ZZ Top fan had crawled under the stage and pulled the cables out. I found the chief electrician and he plugged everything back in so Aerosmith could finish.

Then when ZZ Top were on stage, my assistant comes running up: “You gotta come backstage right away.” As I arrive at the Aerosmith encampment, I see a chair come flying through the windscreen of a Winnebago! They wrecked two or three of them and squirted ketchup and relish all over the insides. Their manager, David Krebs, demands his cheque for the remaining portion of the fee.

I said: “Do you see the damage they’ve done?” And he says: “I see it and you deserve it. You didn’t read the rider, did you? The towels were light blue, we ordered dark blue.” I said: “I’ll send you your cheque after we’ve subtracted all the damage they’ve done.” It came to around $15,000.

Meanwhile, the crowd is out there going crazy for ZZ Top. But the next day the newspapers said 250 people had been injured by broken glass, and so many overdoses and broken noses and so on.

Dr Joseph Fiengold (physician, the Pittsburgh Pirates): It was the most horrible thing I have seen since World War II. I was so busy I could have had a heart attack. I had three well-trained nurses and they were shocked.

Rich Engler: When we checked, only about 98 people had received treatment at the stadium and only about 36 were taken to hospital.

Billy Gibbons: The next day was a game, and the players complained because the animals had gotten loose and put divots in the field. “Hey! Your buffalo just escaped and he’s making third base!”

Paula Helene: By this time some of the live cacti we used on the stage were starting to look bad. So if we were staying in a hotel that had a healthy looking cactus, in the dead of night we’d dig it up and replace it with our ailing cactus. That’s how we kept good-looking cacti on the stage.

Micael Priest: On the second leg of the tour, in Fort Worth [November 28, 1976], there was a brand-new convention centre with huge sliding doors all the way to the roof. By that point, Bill Ham’s paranoia about fans pursuing the band was such that he was hiring nine stretch limos for every show. He would put the boys, individually, in three of them, and then six decoys in the others, just to try to make sure the band would get safely from place to place.

So they had these limos all lined up backstage at Fort Worth, and as they were leading the buffalo on to the scissor lift for rehearsal, the animal jerked his nose-ring out, so he’s throwing his head around in pain, snorting and wild-eyed. He sees this tall strip of light streaming in through the doors in the distance so he heads straight for it.

Between him and the light, of course, are the limos with the drivers inside. He charges right between the first two, but then gets jammed between the next two. The driver wakes from his nap, looks over, and not five inches from his eye is the face of this insane buffalo, sneezing and blowing blood all over the window. He had the presence of mind to lock the door, so it at least couldn’t get inside.

Billy Gibbons: When we started getting into cold weather the rattlesnakes went into hibernation. They were rather lifeless. Where do you go to find lively rattlesnakes? Well, sure enough there was a guy in South Texas that ran a rattlesnake farm, and it was still warm down south. He said: “You need some? Sure. I’ll send you some fresh ones.”

Jay Boy Adams: I was there for the final show of the fifth leg [December 31, 1977, Tarrant County Convention Center, Fort Worth, Texas]. By then, of course, everyone was tired, but whenever they walked on stage they either played an excellent show or a killer-ass excellent show.

Ralph Fisher: I was left with nothing but the highest respect for that band. They were gentlemen, they treated everyone honestly. I never once saw any of the band doing drugs. I only saw them doing business, getting on planes, performing. They’d have a pretty good party after it was all over, though.

What happened next?

By the time the tour rolled to a close 18 months later, ZZ Top had played 89 shows to a total of 1.2 million people – a record at the time. Plans to bring it to Europe were scuppered by quarantine restrictions.

Of the people involved in the tour, Bill Narum and Micael Priest became leading figures in the Texas art scene (Narum died in 2009, Priest in 2018). Ralph Fisher was subsequently inducted into the Texas Rodeo Cowboy Hall Of Fame, and now runs Ralph Fisher's Photo Animals, a facility in La Grange that offers steer photos, armadillo races, mini beer burros and chicken poop bingo.

In 2006, ZZ Top ended their lengthy relationship with Bill Ham, but he continued to run his management company in Houston. He died in 2016.

Of the six vultures called Oscar, one was reunited with ZZ Top onstage during a show at the Fayette County Fairgrounds, La Grange, in 2015. He was more than 50 years old, and the oldest living buzzard in captivity.