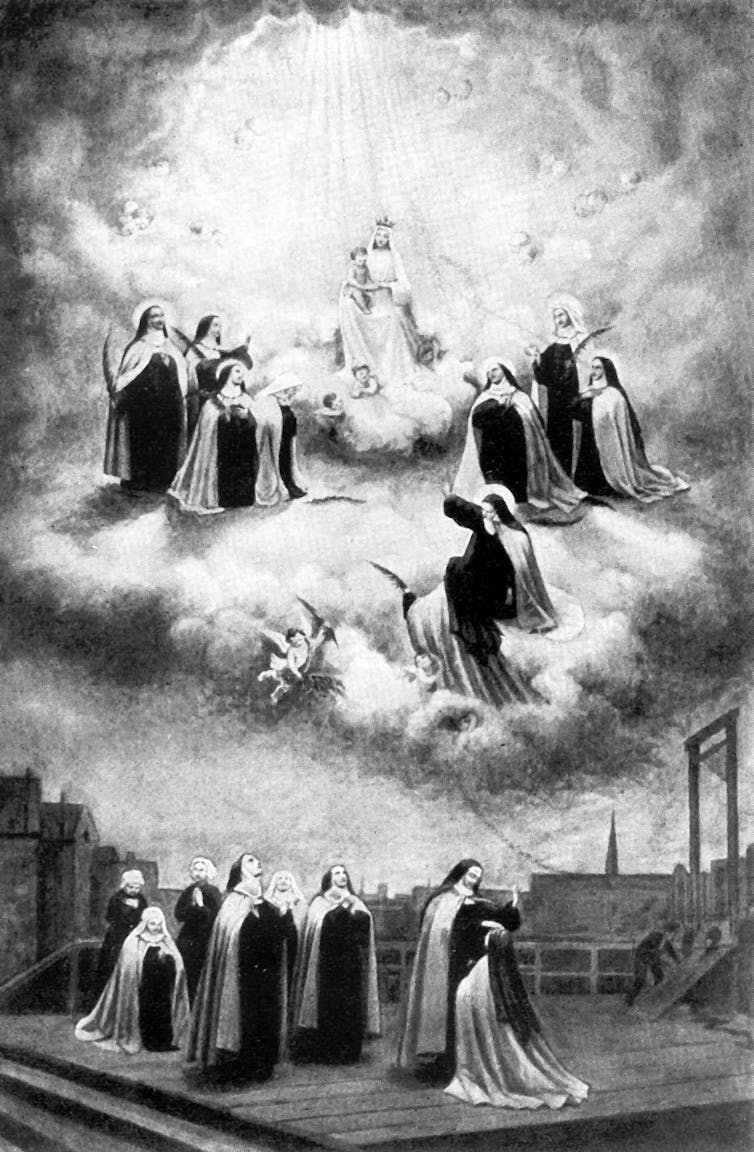

The Martyrs of Compiègne, a group of 16 Discalced Carmelite nuns executed during the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution, were canonised by Pope Francis on December 18.

Their extraordinary faith and courage in the face of death offer timeless lessons on conviction and resilience.

These nuns, led by their prioress Mother Teresa of St. Augustine, embraced their fate with a profound sense of spiritual purpose, leaving an enduring legacy.

Religion and the French Revolution

Established in the 16th century by two saints, Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, the Order of Discalced Carmelites is a Catholic religious order. The name of the Order includes the designation “discalced”, meaning “without shoes”, referring to their rule to go about barefoot or wearing sandals.

The Carmelite nuns dedicate themselves entirely to a contemplative way of life and live in cloistered monasteries.

The French Revolution, marked by its anti-clericalism and radical reorganisation of society, profoundly disrupted religious life. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790 made religious vows illegal, forcing the majority of monastic communities to disband.

The religious community of the Carmel of Compiègne, established in 1641 and renowned for its piety, refused to break up. In August 1792, the revolutionary government decreed the closure of all monasteries occupied by women.

The nuns’ expulsion from their cloister followed in September 1792. The nuns maintained their communal life in secret, relying on the support of the local community. They continued their prayers and acts of devotion.

The nuns’ commitment was inspired by a prophetic vision experienced in 1693 by Sister Élisabeth-Baptiste, who saw her sisterhood destined to follow Jesus Christ in a profound act of sacrifice. The written record of this vision, preserved in the monastery’s archives, deeply resonated with the Carmel’s prioress, Mother Teresa, as Catholics endured the turmoil of the Revolution.

In November 1792, the prioress proposed an extraordinary act of consecration: the nuns would offer their lives for the salvation of France and the Church. Since then, each nun daily offered herself for the salvation of France, praying for peace and unity.

Arrest and trial

The Revolution’s intensifying hostility toward religious communities led to the nuns’ arrest in June 1794 at the height of massacres and public executions known as the “Reign of Terror”.

Accused of being “enemies of the people” for their continued religious practices and perceived loyalty to the monarchy, they were transferred to Paris’s notorious Conciergerie prison that held such prisoners as Queen Marie Antoinette.

At their trial on July 17 the public prosecutor, the notorious Antoine Quentin Fouquier de Tinville, charged them with fanaticism, defined as their steadfast attachment to their faith.

The nuns confronted the prosecutor, demanding a definition of fanaticism. This act of defiance highlighted the absurdity of the charges and revealed the regime’s persecution of religious belief as a threat to its revolutionary ideals.

Execution and legacy

That evening the nuns were paraded through Paris in open carts on the way to execution. They sang hymns such as Salve Regina and Miserere.

In doing so, they continued to proclaim their adherence to their faith, preparing to give their lives so the terror might end and French Catholics would no longer face persecution.

Upon reaching the guillotine at the Place du Trône Renversé, they renewed their vows. Sister Constance, the youngest at 29 and still a novice due to revolutionary laws banning religious professions, was the first to ascend the scaffold. As she approached her death, she began chanting Laudate Dominum omnes gentes, a hymn proclaiming God’s mercy.

One by one, the nuns followed.

The executioner and witnesses reported their extraordinary composure and the solemn silence of the crowd. Mother Teresa, the last to die, upheld her role as a spiritual leader to the very end, completing the community’s sacrificial offering.

Ten days later, the revolutionary leader and architect of the Terror Maximilien Robespierre was arrested and executed, effectively ending the Reign of Terror. The nuns’ martyrdom has been interpreted by French Catholics as hastening Robespierre’s demise, their sacrifice seen as a powerful act of intercession for a nation in turmoil.

Lessons on conviction and resilience

In 1906 Pope Pius X beatified the Martyrs of Compiègne. Beatification means the Church recognised their entrance to heaven, and that they could intercede on behalf of those who pray in their name.

Last December, Pope Francis canonised the women via equipollent canonisation. Also known as equivalent canonisation, this is a process by which the Pope declares a person to be a saint without the usual judicial procedures and formal attributions of miracles typical in the canonisation process.

This rare procedure is used for individuals who have been venerated since their death and whose sanctity and heroic virtues are already firmly established in Church tradition.

The Martyrs of Compiègne’s feast day is celebrated on July 17, the anniversary of their ultimate act of faith.

The Martyrs of Compiègne exemplify unwavering faith and courage. Their decision to offer their lives as a collective sacrifice underscores the transformative power of conviction. Faced with the threat of death, they demonstrated remarkable unity and spiritual fortitude, finding strength in their shared commitment to God and their community.

Their story challenges us to reflect on the nature of resilience and the values we uphold in times of crisis. By standing firm in their beliefs, they revealed the profound impact of faith and the capacity of the human spirit to endure adversity.

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.