On 12 June 1962, guards at the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary began their day with a startling discovery. Three inmates were missing from their cells. John Anglin, Clarence Anglin, and Frank Morris had escaped. On their pillows were papier-mâché replicas of their own heads, meant to mask their absence and throw guards off their scent.

What happened to them remains a mystery to this day.

John and Clarence Anglin, brothers from Donalsonville, Georgia, had been sent to Alcatraz after robbing a bank in Columbia, Alabama. Frank Morris had previously been imprisoned for bank robbery, escaped, and was sent to Alcatraz after being convicted of a burglary. Investigators would later theorise that the three men began planning their escape six months before it unfolded, beginning in December 1960.

When Alcatraz opened in 1934, it was conceived of as a “a maximum-security, minimum-privilege penitentiary”. The prison, located on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay, was intended as a tough-on-crime show of force — per the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), “to show the law-abiding public that the federal government was serious about stopping the rampant crime of the 1920s and 1930s”.

Alcatraz was meant for “prisoners who refused to conform to the rules and regulations at other Federal institutions, who were considered violent and dangerous, or who were considered escape risks”. In the BOP’s own words, it was “designed to be a prison system’s prison”, where prisoners learned how to earn “privileges” (such as “working, corresponding with and having visits from family members, access to the prison library, and recreational activities”) before they could be sent to serve the rest of their sentences elsewhere.

So, how did the Anglin brothers and Morris make it out? According to the FBI, they loosened air vents in their cells, creating enough space to allow them to get out. Then, they used an unguarded utility corridor as a “secret workshop” where they assembled the necessary tools for their escape. These included, according to the bureau, homemade life preservers and a life raft made from 50 raincoats. (The men are believed to have found instructions on how to assemble the makeshift life preservers and life raft in magazines.) They also manufactured a periscope-like tool to keep watch on the guards while they worked, wooden paddles, and a tool to inflate the raft. “Using a network of pipes,” the men “climbed up and eventually pried open the ventilator” at the top of the building. They made a fake bolt using soap to conceal their preparations.

On the night of their escape, the men are believed to have left their cells, collected their supplies, and climbed their way up to the roof. “Then, they shimmied down the bakery smoke stack at the rear of the cell house, climbed over the fence, and snuck to the northeast shore of the island and launched their raft,” per the FBI’s account.

Whether the men survived is a mystery the FBI has not been able to solve.

Bodies were never found. Over the years, alleged evidence of the men’s survival has surfaced, prompting debates among investigators, experts, and the Anglins’ relatives. In 1979, the FBI closed its clase, admitting that its investigation, “which lasted for nearly two decades, was unable to determine whether the three men successfully escaped or died in the attempt”. The US Marshals took over the probe and have kept it open since.

Ken Widner, a nephew of John and Clarence Anglin, is convinced his uncles survived the escape and made it off the island. He and his brother David have done a number of media interviews over the years, sharing what they believe to be proof that their relatives made it out of California safely.

As a child, Widner, whose mother Marie Anglin Widner was John and Clarence’s sister, was used to hearing the tale of his uncle’s escape from Alcatraz. “It’s been a part of my life ever since I can remember,” he tells The Independent. “It was always something that was talked about in family reunions.”

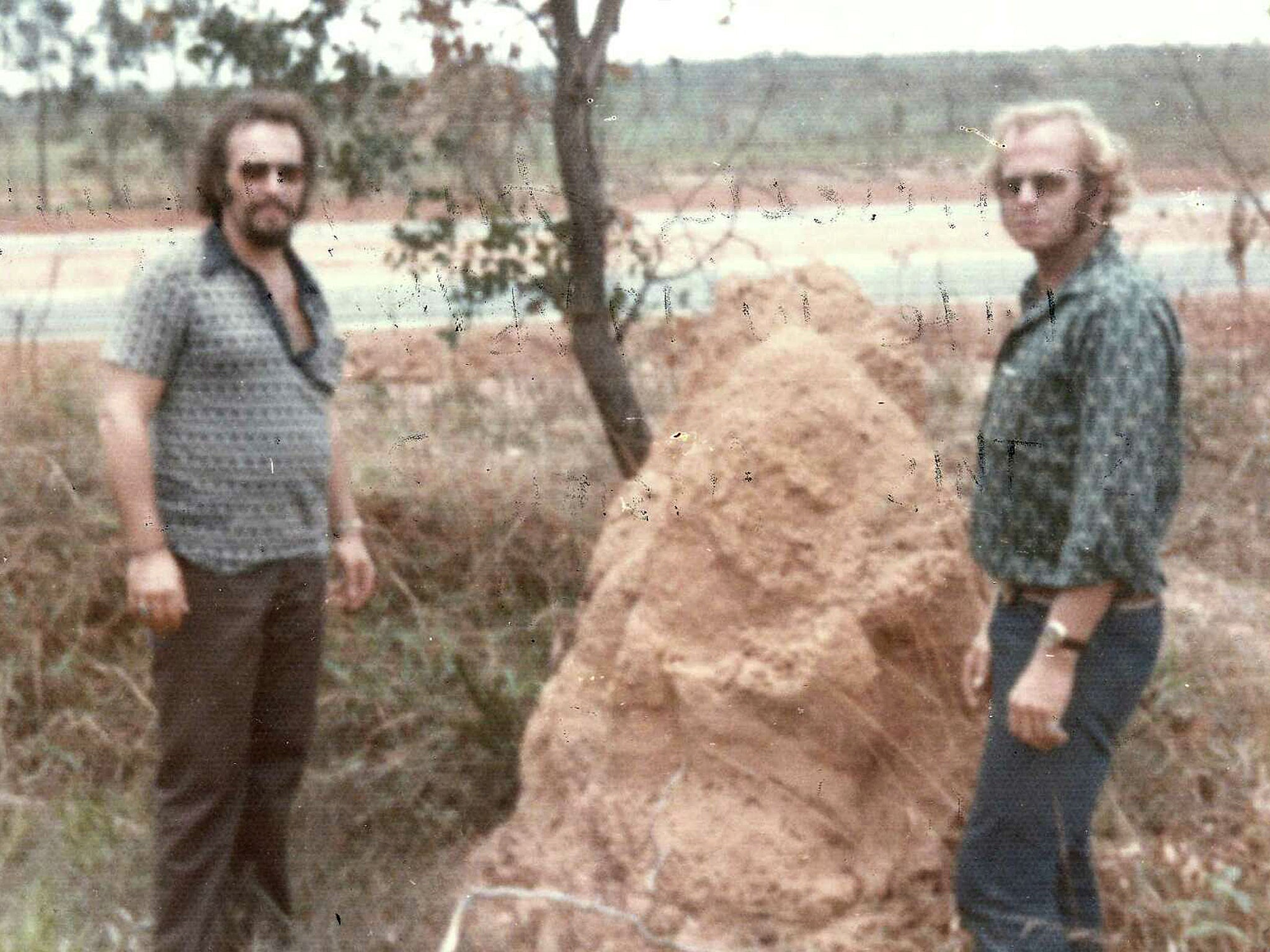

In 2012, the case received renewed attention as media outlets marked the 50th anniversary of the Anglins’ and Morris’s escape. That’s also when Widner became determined to dig into the case further. In 2015, he and his brother David participated in a History Channel special in which they unveiled what they say is a photograph of John and Clarence Anglin, alive and well, in 1975.

According to Widner, the photo was taken by Fred Brizzi, a family friend, who gave it to the Anglin family in 1992. “It stayed in my mom’s collection for all that time,” he says, until he discovered it himself. In a History Channel special titled Alcatraz Escape: The Lost Evidence, Ken and David Widner are shown bringing the evidence to investigators and theorizing that their uncles built new lives as farmers in Brazil following their escape.

“I believe it was a way of feeling, like, OK, enough time has passed,” Ken Widner tells The Independent. “... I believe it was a way for them to let the family know, ‘Hey, we did make it, we’re OK, we didn’t die, but we can’t come home.’”

The photo has been the subject of intense commentary and speculation. It’s grainy – as can be expected for an older image – and features two men, both wearing sunglasses, looking in the direction of the camera.

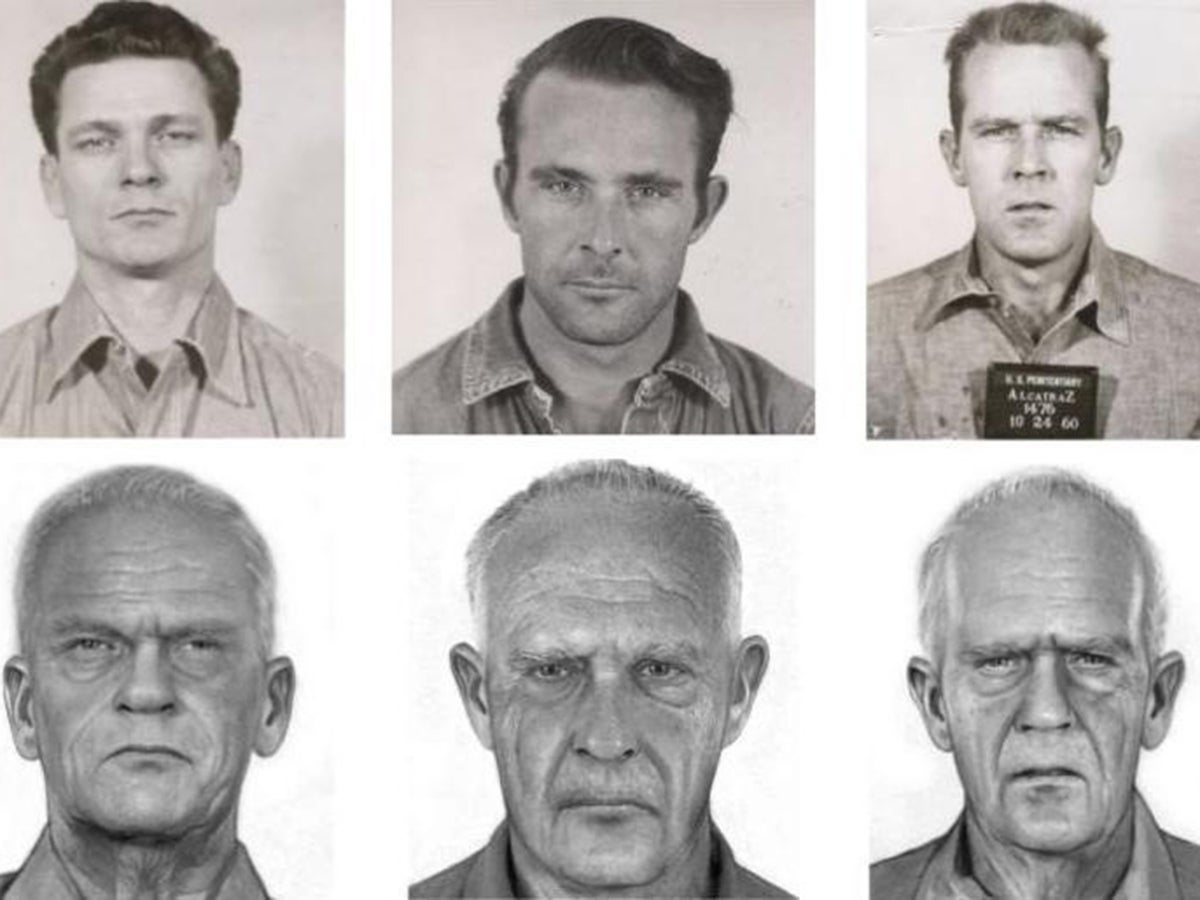

Michael W Streed, a retired police sergeant and sketch artist for the Baltimore Police Department who now offers services as a forensic imaging expert, is featured in Alcatraz Escape: The Lost Evidence analysing the image, comparing it to the three men’s booking photos, and offering an encouraging assessment, saying he sees “more [in the images] that’s similar [to verified images of the men] than I see that’s dissimilar”.

Michael Dyke, a now-retired deputy at the US Marshals, investigated the fate of the Alcatraz escapees for years. In 2016, he expressed doubts about the photo, telling ABC30 that some physical characteristics suggest it doesn’t depict the Anglin brothers. Though, he also said it couldn’t be ruled out as a possible lead.

Now, Dyke is more definitive. “After working the case for 17 years, it is my opinion that [the three men] very likely did not survive the first night of their escape,” he tells The Independent. “Because no body has been recovered, you can never say that a hundred per cent, but based on all the evidence, more than likely all three of them died that night and were swept out to the ocean.”

Of the photo, Dyke says this: “You cannot do facial recognition on either of them. Because in order to do facial recognition, you need to see the eyes, the pupils, the corners of their mouths. Also the height of the ears on their heads.” The men in the photo, he points out, both have long hair, sunglasses, and facial hair. That means there is “no valid way” of conducting facial comparison on either of the men, he says.

Other elements can be examined, he adds, which are unlikely to change over time, such as the length of the arms and of the fingers. “I have existing photographs of both Anglin brothers showing their full- length body. Both had unusually long arms,” he says. “Both subjects in the Brazil photo have short arms. When you do measurements on each, you can easily tell that the two men in the photo are not either Anglin brother.”

Fred Brizzi died in 1998. In 2015, his widow Judith Brizzi told the Daily Mail that her husband had “never said anything to [her] ever about those men escaping from Alcatraz”.

“He showed me the photograph because of the size of the anthill. I’ve no idea who the men are in the photo and Fred never talked about them,” she added. “He did say the photograph was taken on his trip to Brazil.”

Ken Widner and his brother have offered up another piece of what they view as evidence that their uncles lived. It’s an audio tape Widner says was recorded by their mother while Brizzi explained what had happened to the Anglin brothers.

On the phone with Ken Widner, I ask if he’ll play part of the tape for me. He agrees, and within a few seconds, audio plays from the other end of the line. By Widner’s own admission, it’s tough to make out what the people on the tape are saying, because the recording is old – and it probably doesn’t help that I’m listening to it over the phone. A clearer version aired on the History Channel – the same section I’m hearing. “Nobody positively, absolutely knows they’re alive, really, but me,” Brizzi says on the tape.

Dyke says he has listened to the entire tape and sees inconsistencies in Brizzi’s narrative. To him, a lot of Brizzi’s version of events “does not make sense and is exaggerated”.

Think about the Alcatraz escape long enough, and you will inevitably start wondering about the bodies. In the 60 years since the escape, no body was ever found. If the men had drifted off into the ocean, or if they had drowned, wouldn’t their remains have floated to the surface by now?

Well, not necessarily. According to a 2002 New York Times Q&A (which was not specifically related to this Alcatraz escape but shared general information about what happens to human bodies in water), “a body in deep, cold water may never resurface” because the cold water slows down decomposition, and therefore the release of gasses which cause bodies to rise to the surface.

Adding to that, Dyke says, is the sea life in the Bay Area and in the nearby ocean, which includes “crabs or other bottom-dwelling sea creatures [which] will usually poke holes in the body”, also preventing the buildup of gasses that would cause a body to float.

“Based on the tidal charts from that evening, it is more than likely they were swept directly out to the ocean,” Dyke adds. “If they had left a half hour earlier in the day, or even an hour later in the day, their bodies may have been recovered.”

But, as Ken Widner wonders over the phone, if investigators are so convinced the escapees drowned, why don’t they close the case? Why has the FBI released age-progressed images of all three men?

“As long as the bodies haven’t been recovered, there is still a chance that they could be fugitives and alive, even if the chance is very small,” Dyke says. There are procedural reasons, too: as long as there is an active fugitive warrant for the three escapees, the US Marshals Service won’t close its case, he says, and it’s “not standard practice to request a warrant be dismissed without solid evidence to support it” – such as remains or DNA evidence being found.

Back in 2012, on the 50th anniversary of the escape, US Marshal Don O’Keefe told Reuters the ongoing investigation “serves as a warning to fugitives that regardless of time, we will continue to look for you and bring you to justice” – language that suggested the desire on the service’s part to send a message and project an image of tenacity, perhaps more than anything else. The US Marshals Service has previously said it will keep investigating the men’s fate until they are either arrested, shown to have died, or are all supposed to have turned 99. This would put the deadline to officially solve the case in 2030.

Ken Widner says he and his family don’t believe the Anglin brothers are still alive, but rather that they survived the escape and died later on. He thinks any investigation going forward should aim not “to find them alive, but to find their grave.”