They came, like the man in the video, from all over, from Sudan and Kenya and Pakistan and elsewhere to Qatar. They came, this particular group, to work security at World Cup stadiums and venues, to send money home, where conditions are grim; work, sparse or nonexistent.

The man in the video wears a gray shirt, glasses, a neatly trimmed black beard and the most somber of expressions. He sits in front of a brick background and appears to be filming on a cellphone. He says he cannot give his name, because he fears for his safety and because he wants to work. But he still has a lot to say.

“I will tell you the real story of what happened,” he says.

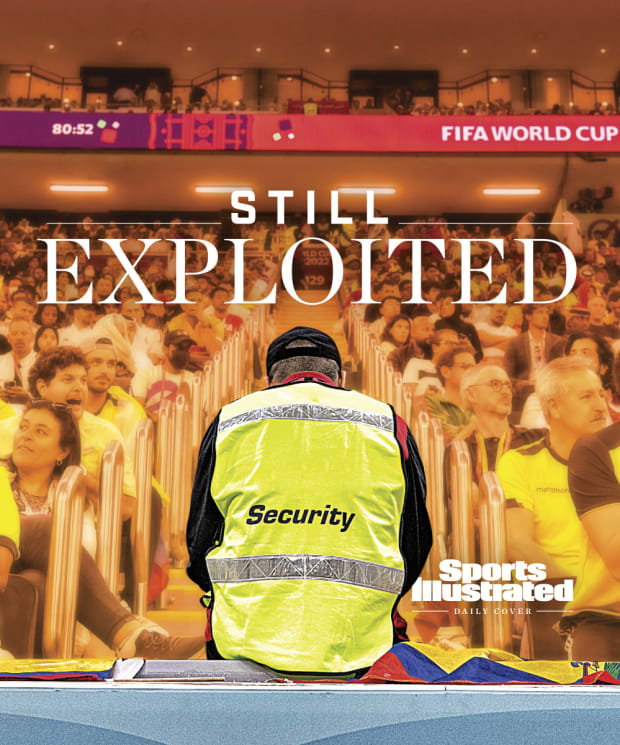

Christopher Pike/Bloomberg/Getty Images; Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin

This man was desperate. So desperate, in fact, that he left his home in Pakistan, paying a recruiting agent to set him up with employment in Qatar. He borrowed most of the sum required—17,000 Qatari riyal, or roughly $4,700—from relatives and friends. But after asking and begging everyone he knew, he still didn’t have enough. So he sold his grandmother’s wedding ring at a pawn shop and left for Doha in advance of the biggest tournament in sports, which unfolded last November and December.

Upon arrival, he settled into housing provided by the company that hired him and the five other security guards who spoke to Sports Illustrated, a private firm, Stark Security Services. He says his contract dictated things like length of employment (six months, same for all six) and salary (2,700 QAR, or about $750, per month with some variance across the sampling of six). Why Stark offered contracts that ran longer than the tournament, none of them can say. But human rights advocates can guess that the lengths were essentially incentives; likely grounded, one says, in exploitation.

The man in the video found the Stark-provided room and board decent, and, overall, he liked the work; in his case, body-scanning journalists with metal-detecting wands at the Main Media Centre (MMC). This was the World Cup, after all; excitement, travelers, purpose, connection. He became one small but not insignificant piece of an awe-inspiring global event.

The problems started long before Argentina’s triumph over France. But they were exacerbated on the day of the final, Dec. 18, when the man in the video—and many of his colleagues—were informed that their jobs were being terminated. Even more of their coworkers were informed later, the same way, as mass firings took place in waves. Some stayed in the Stark Security residences, hoping for new postings so they could serve out the length of their contracts. Only some had completed even their fourth full month of work. Many were told they would receive their wages for December only if they signed paperwork accepting their termination, according to multiple guards SI spoke to, as well as Jason Nemerovski, a researcher at a human rights nonprofit called Equidem, who spoke to dozens more. The vast majority of the guards were scheduled to make the same amount, that 2,700 QAR, even those among them who worked as supervisors. All the guards, regardless of how long they had worked or how often or much they had been paid, were instructed to leave the residences.

Most stayed, according to those who corresponded with SI. They told their bosses they wanted to fulfill the obligations in their contracts, to earn their wages. And, if there was simply no additional work to complete, they still needed to be paid.

Initially, the men say, Stark officials seemed intent on utilizing indirect pressure. The Wi-Fi went out, so the guards couldn’t call home, speak with family or look for other jobs. They say their minders also stopped feeding them, as their contracts required. Stark stopped providing even water for their apartments, they say. After all this, some did leave, and, worse yet, they say they could depart only after signing paperwork that said they had finished their contracts and that Stark no longer owed them money, according to multiple guards, as well as Nemerovski. But many, like the man in the video, still remained.

He is now back home. He has no money and, worse, a gigantic record of debt rather than dollars. Representatives looking to collect the fees for the recruiting agent, he says, set up in front of his residence, waiting for the money. “We did not do anything wrong,” he says.

He’s referring to events from January, more than a month after that World Cup final. That’s when the transport—four buses in total—pulled up to those apartments. And when all of those guards from all over the world piled on. According to three of the guards SI spoke to and Nemerovski, that’s when Stark officials told all the guards, hundreds in total, to stop by their office headquarters. Come, they said, you will be paid in full.

Yukihito Taguchi/USA TODAY Sports

As another World Cup plays out, with FIFA basking in the glow of a tournament returned to freer, more democratic climes, the fallout of last year’s men’s edition continues for the many workers who were exploited as part of its preparation and execution. In mid-December, two days before the World Cup final, SI published a story on Equidem, a global human rights organization, plus the World Cup migrant workers it fought for and represented. Equidem is just one of many similar groups. The piece focused on just its work ahead of the World Cup and the staggering suffering it uncovered among the workers who made it possible.

The story described the conditions as brutal—cramped quarters, broken bathrooms, little water, obscene heat, almost no breaks. Companies hid workers from inspectors, shifting them to other work sites. Sure, Qatar approved and enacted reforms, at least in theory. The end of Qatar’s kafala system marked one, for instance, ending (also in theory) a long-held and accepted form of indentured servitude. But after all the deaths—as many as 6,500 workers before a single match began, according to The Guardian—came all the money. FIFA bragged that it made $7.5 billion on this tournament alone. Qatar added more than $17 billion to its economy, according to the figures officials noted in public forums. And yet, in practice, on the ground, reforms seemed more like suggestions.

Just ask Jorum Murigi, a Stark security guard from Kenya. He sends pictures over WhatsApp. That’s him, posing proudly in front of Stadium 974, the one fashioned from shipping containers and showcased all over international television. That’s his work permit: application number (ES2022080517), employer’s number (17-2104-63) and issue date (8/28/22). Six months of work, with full payment, rather than the standoff, would have ended Feb. 28 this year. But his conundrum, Murigi says on a phone call, started well before that.

He says that wages were delayed during the tournament, even—that complaints, which had been “encouraged” (also in theory), were never actually heard. FIFA president Gianni Infantino had told assembled journalists last November, lecturing, while wagging his fingers, that any worker owed any wages could simply show up at their respective office and collect. There were more formal ways to lodge complaints as well. For any of those methods to work, though, would have required follow-through behind the policies that human rights advocates say were set up simply to appease deep and widespread concerns long enough for Qatar to host—and rake in cash. Murigi says he and his fellow workers helped stage a successful tournament, by most measures, especially revenue collected. “Now, they’re done with us,” he says.

Conditions worsened over time, he continues, pointing to the nadir: coming to work the day Stark relayed news of his termination, effective immediately. Murigi is back in Kenya now; unemployed, like the others who spoke to SI; and in debt just like them, too. Before leaving for Qatar, he was a college student. Now his studies are on hold. He, too, liked the job. He calls working the World Cup an honor, still.

“I’m really angry,” Murigi says. “We told them we are willing to work and cooperate. They said we committed a crime.”

Fauzan Fitria/Alamy Stock Photo

Stark is managed by Estithmar Holdings. The largest shareholder of Estithmar is Moutaz Al-Khayyat, a member of a prominent Qatari family best known for airlifting 4,000 cows into the country in 2017. The operation was a response to a group of nearby Arab countries blockading Qatar, resulting in a dairy shortage. Al-Khayyat is linked prominently to the royal family and its regime.

Now, Stark was trying to herd the security guards onto four buses. And that is when Equidem grew laser-focused. They were led by Nemerovski, a young researcher based in Paris. The guards were headed, three of them say, toward Stark’s offices, what officials there referred to as The Tower. The guards weren’t totally naive; it’s not like many expected to just be handed over paychecks, case closed. But they hoped to start a conversation, engage in meaningful dialogue and, at some point, receive payment.

Nemerovski acknowledges that accounts of this afternoon vary; the slight differences, he believes, owe to the specific narrator’s level of involvement. Some say 800 guards were on the buses; Nemerovski estimates it was more like 200 to 300. A few did believe they would collect what they were owed that very afternoon. All wanted the same thing, though. “Our money,” Murigi says.

All six guards reached by SI also agree on what happened next. The ride started with heightened anticipation, nerves and hope blending as the bus rolled toward downtown Doha. As they reached what’s more formally known as the Eighteen Tower, they were stopped. They had been in regular contact with their managers from Stark throughout the tournament and now, Nemerovski relays, they saw their bosses standing in the middle of the road with arms and palms outstretched.

The guards sent SI videos that they say capture this encounter. They’re short clips, ranging from eight to 20 seconds, and they all show the same scene from different angles. The guards are packed onto the buses. They’re wearing their uniforms from the tournament: hats and tracksuits colored black and red. Some are looking at their phones; others, at the people who can be clearly seen standing in front of the lead bus, which is stopped. Chatter can be heard in various languages. The majority of the guards interviewed by Equidem came from Pakistan and Kenya, with some from India, Nepal, Ghana and Gambia as well. And two of the six videos that were sent to SI also show what happened next: In one, a police car enters the frame. In another, the car is parked in front of the lead bus, lights flashing, so close that the bumpers are almost touching.

Turns out, someone had called the police. It is illegal to protest in Qatar without permission from the Ministry of the Interior. But, all insist, they had no plans to protest, informally or otherwise. Nor did they protest, all maintain. No signs. No chants. No rogue picketers. The videos show none of that. But the state came to label it a protest.

They had been duped. Or at least felt that way. “We didn’t know that you were playing with us,” the man in the video says. Nemerovski says that he hasn’t heard a recording of the promises that Stark allegedly made to the security guards. But dozens have confirmed to him, directly, the same specifics of how the idea of meeting was presented to them. The videos, he says, make the guards’ other point: that they were not protesting. “I’ve seen a protest,” Nemerovski says. “I know what a protest looks like. And this was absolutely not a protest. Nobody said it was. Everyone was simply asking about the meeting.”

The meeting that never actually happened.

As soon as Nemerovski read about what happened, he started trying to track down guards. As far as human rights avengers go, he is typical and not typical at all. He completed a master’s degree at the Graduate Institute in Geneva last June. He studied international development, with a focus on migration, and, for his capstone project, interviewed people at organizations like Equidem, where he spoke with Mustafa Qadri, the organization’s founder and CEO. Specifically, Nemerovski studied Qatar and recruitment fees, which is one Equidem focus. After finishing the project, ending a stint at UNI Global Union—a federation of unions from across the world—Nemerovski didn’t want to abandon the work that had started to fulfill him. So he called Qadri back and asked for something more permanent.

Come on board, Equidem said.

Their conversation led to an internship, and the internship led to a full-time gig. Nemerovski understood the landscape in Qatar. He knew about the kafala system that had long granted Qataris power over migrant workers they helped bring in. He knew that where workers came from often dictated which jobs they could hold. Knew that security guards were often from all over, placed via recruiting agents. He also knew what everyone knew, the reality that the government desperately wanted to change the perception of, through sports. “There’s no free expression,” Qadri says. “The Gulf is a profoundly unfree part of the world.”

To Equidem—and many other advocate groups—Qatar and its enablers executed a plan straight out of a sportswashing playbook. They would change, they insisted. The world would see, they insisted. That same world would be welcomed, despite a host of exclusionary laws. The changes—in systems, safety, rights and infrastructure—would provide a blueprint for other countries from the Gulf region who wanted, just as desperately, to host major future sporting events, from the Olympics to major fights in boxing and MMA to maybe even an NFL game. Once the tournament unfolded, the news cycle moved on, but Nemerovski kept trying to reach guards. As of late March, he had conducted 43 in-depth interviews with aggrieved security guards alone, in addition to dozens of shorter calls. He says all shared similar stories to those relayed by the six guards to SI.

“The caravan moves on,” Nemerovski says, “which is exactly what the government wants.” Qatar and FIFA, he says, are “banking on the idea that people will have forgotten, and also, frankly, that human rights don’t matter.”

Every day, Qadri says, hundreds of emails and phone calls and social media messages related to Qatar flood in. He considers the volume thus far merely a start. Nemerovski joined one group chat for just Stark guards from Pakistan; it already had 55 members. Many declined to speak with him, for fear of retribution or because they wanted to go back to work.

FIFA officials gathered in Rwanda to reelect Infantino in mid-March. He won a second four-year term. The organization’s news release reported that Infantino pledged to grow the game and noted that, for the first time ever, the elective FIFA Congress was being held in an African country. All of which, to human rights advocates, signaled FIFA’s true aims: more fans; more money; and … about those human rights efforts? Well, according to the organization Freedom House, which rates countries all over the world on human rights, Rwanda currently scores a 23 on a scale of 100, placing it ahead of countries like Russia (16) but behind those like Turkey (32), and squarely among countries considered by the org as NOT FREE. (Qatar scored a 25.)

“I mean, they made a [ton of money], right?” Qadri says of FIFA and the Qatari government. “And [Qatar organizers] got away with murder and [companies] stealing workers’ wages. If you’re striving to make your life better, through hard work, you should get rewarded, not punished. But right now, it’s the bad guys getting rewarded and the good guys getting punished.”

Qadri believes Infantino is defining success, in part, by the execution of the tournament. He means from a pure soccer perspective and a safety one. Both went well. But, he asks, “Who made it safe?”

Matthew Ashton/AMA/Getty Images

Back on the bus, the workers started panicking. The officers weren’t leaving. Nor were they allowing anyone to climb off. After several minutes, maybe an hour, the caravan began rolling again—but not toward Eighteen Tower: in the opposite direction.

The guards clustered together inside had no idea where they were headed. They found out when drivers pulled into a deportation center and all were hustled inside. On Day 1, the guards who corresponded with SI say, deportation officials took all forms of identification from them, including passports. On Day 2, the guards say, their eyes were scanned and their fingerprints were taken. On Day 3, the deportations started. By Day 5, the forced exodus was all but done. Equidem interviewed guards who were deported on Jan. 25, 26, 27 and 28.

Many signed the termination paperwork; some say they were threatened with longer stays in the center if they did not, and told that, if they did, they would be allowed back into Qatar to work. Some of the signees received part of their December wages, Nemerovski says, nothing more. Some time between the ill-fated bus trip and the departures, Nemerovski and the guards who spoke to SI say, someone had gone to the residences, packed up the guards’ belongings and called families back home. That’s precisely where they themselves were headed.

Every person on the group chat from Pakistan that Nemerovski joined was deported. Other guards, who hadn’t been on the bus, managed to stay by choice. Some fulfilled their six-month contracts. Some accepted their fates, terrible as they were, and simply moved on.

In response to questions from SI, Qatar’s International Media Office replied that government authorities had in fact launched an investigation into Stark and “found that the company failed to comply with all of Qatar’s labour laws.”

“The Ministry of Labour is in the process of penalizing the company through the proper legal channels, including banning the company from future projects until all issues are resolved,” the statement continued. It went on to say that workers “were renumerated in full for their services and their contracts were concluded in accordance with their specified terms.” Nemerovski and Equidem contest that point—they say the workers were never fully paid. Stark did not respond to SI’s request for comment; Estithmar Holdings also did not return messages.

The statement also said that Qatar “does not arrest or deport workers for seeking to resolve their employment disputes” and argued that all workers’ rights were upheld—another point Equidem and the workers who spoke to SI hotly contest. The Qatar media office statement went on to emphasize the labor reforms and complaints mechanisms that were implemented before the games, which it said corrected many of the issues in the country.

“Qatar’s labour reforms are an integral part of its World Cup legacy,” it said.

Equidem as an organization has interviewed more than 1,000 workers who toiled to make the World Cup possible. Very few received the full compensation agreed to in their contracts, Nemerovski says, while some incurred penalties for violating their agreements. And, Qadri says, “ Qatar has just said, Well, no, that didn’t happen.” And that, so far, is that.

This is what drives Nemerovski and his colleagues: the grand injustices. The billions of dollars collected vs. the millions of dollars in unpaid wages. The machine opposite those who built it. The reforms contrasted by reality.

They’re not alone, Nemerovski and his avengers. While FIFA geared up for Infantino’s reelection, other human rights organizations released similar statements grounded in similar findings. They alleged that in the leadup to and during the World Cup, Qatari and World Cup officials allowed for illegal recruitment fees, overlooked health and safety risks, overworked their employees, discriminated based on nationality and used violence, either in threats or in practice, to cover up forced labor practices rather than address them. All that while also interfering with investigations, intimidating whistleblowers and ignoring legitimate complaints. (FIFA has routinely defended its actions related to the Qatar World Cup; at a now infamous pretournament press conference, Infantino lashed out at critics, particularly from the West, saying, “Who is actually caring about the workers? FIFA does. Football does, the World Cup does and to be fair to them, Qatar does as well.”)

The coalition of Global Union Federations sent out a news release noting that “employer lawlessness increased” during the tournament, while dialogue between advocates and government officials came to “an abrupt halt.” Those officials blamed private companies for “going rogue.” FIFA threw up its hands. Violations went unpunished. The release continued: “To date, there is not a tangible or lasting legacy of the FIFA 2022 World Cup of which Qatar, FIFA, and the world could be proud.”

In March, the International Labor Organization called for the Qatari government to comply with fundamental rights and principles, from freedom of association to the rights to organize, collectively bargain and strike. The ILO called for recognition of the exploitation and physical harm suffered by migrant workers who made the World Cup with their bare hands; remedies for families of those who died or endured; a Migrant Workers centre for those who remain; independent reviews; and a detailed, specific plan for future improvements. All the same stuff groups called for before the tournament. And all the same stuff Qatar said it would “address.”

“It’s infuriating,” Nemerovski says. “They’re treated like literal pawns that can be thrown away at the end of a game. They’re bodies and nothing else, in these people’s eyes. They don’t have families. They don’t have children. They don’t have parents. They don’t have stories. They’re nothing. They’re just flesh.”

Three of the workers from the buses remain in prison in Qatar. All were alleged, according to Qatar Supreme Judiciary Council documents, to have participated in illegal demonstrations. They were sentenced in January to six months in prison and fined 10,000 QAR, or about $2,750, nearly four times their monthly salary. Though six months have elapsed, they continue to be held. As Nemerovski understands what happened, these three men got off of the buses and attempted not to protest but to come to a reasonable solution. In trying to do the right thing for their colleagues and end the issues with Stark, they unwittingly put themselves in danger they never saw coming, Nemerovski says, adding, “If anything, they should be celebrated for trying to peacefully stand up for their rights.”

Equidem met with Pakistani officials on their behalf on June 7, hoping to convince the officials to lobby Qatar for the guards’ release. But those efforts were apparently unsuccessful.

Asked whether he’s worried about the guards who are still in prison, Nemerovski continued to find what positives he could glean. “The thing I feel optimistic about,” he says, “is they did nothing wrong.”

All six guards who corresponded with SI are back in their home countries. None of them have found work. Many had their property, like laptops and cellphones, confiscated, never to be returned. One, when asked whether he had found another gig back home in Kenya, simply laughed. Another, the man from the video, actually wanted to return to Qatar to finish out his contract. As long as Stark would pay him, going back represented his best, even only, viable option.

With hindsight, Qadri says, advocates and their organizations might have spoken more sharply before and during the tournament, if they knew how little the landscape actually would change. They delivered criticisms as politely as possible because they feared being booted from the country and wanted to track down as many workers as they could, file cases and actually help. They could have said: Qatar had no business holding an international sports tournament. Could have said: FIFA is not a force for good in the world—and never was. “We made a mistake collectively,” he says, “not calling b.s.”

Instead, Qadri now looks at Qatar and the World Cup and sees a blueprint for other Gulf states to wink and promise but, rather than change, continue to exploit for revenue and reputational cleansing. He’s still hopeful, but he wouldn’t be doing that job, this work, running Equidem, if he were anything else. If anything, Nemerovski adds, part of the tournament’s legacy will be a nefarious blueprint, at least as he views it: offer open visas, employ migrant workers for only as long as necessary, then say that their asking for the terms in their contract to be completed is a form of protest worthy of arrest and deportation. “That is what’s happening,” he says.

The amount of money required to make the workers whole is pennies compared to what Qatar spent on and took in from the World Cup. Reminded of this, Nemerovski sighs over the phone. It’s also pennies for FIFA. But it’s real money for the workers. “For them,” he says, “it is.”

To Qadri and others like him, everything adds up, so far, to this: monetizing misery. For now—and perhaps forever—that’s the legacy of that World Cup, more meaningful and lasting in the worst ways than Lionel Messi’s triumph or the billions banked. Shameful, Qadri calls this. But also to be expected.