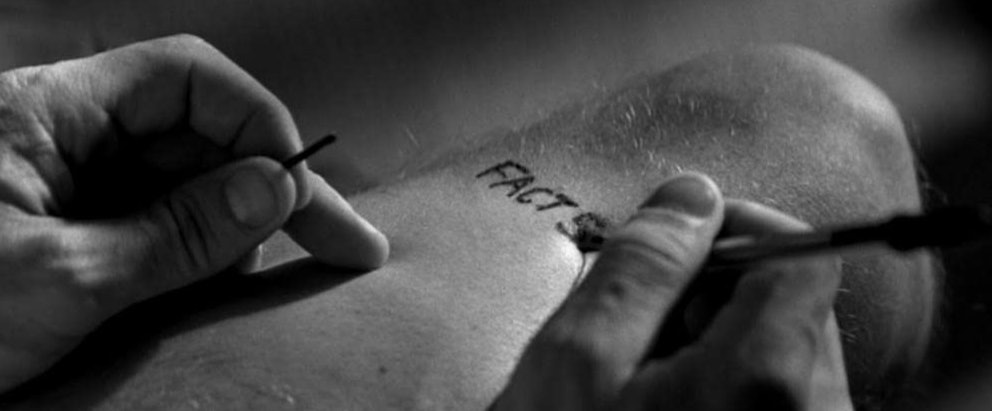

Leonard Shelby lives in a constant state of confusion. The protagonist of the 2000 film Memento tries to make sense of the world by taking Polaroid pictures, jotting down notes, and tattooing messages on his body — a substitute for remembering new info, since his memory always fails.

“I have no short-term memory,” Leonard explains to the clerk at the front desk of a hotel. “I know who I am, I know all about myself, I just … since my injury I can’t make any new memories. Everything fades.”

After being assaulted during a break-in, Leonard sustained a head injury that made it impossible to retain new information. He can’t remember the people he meets, the places he’s been, or things he did even hours ago. But his tattoos and notes remind him to take revenge on an enigmatic man, John G, who he believes killed his wife.

Leonard’s disorienting tale is underscored by a real-life condition, called anterograde amnesia. It’s pretty rare in real life — though it is possible for someone to completely lose the ability to commit new information to memory after a brain injury.

“In effect, the continuous record of [a patient’s] life ceases at the moment they sustained the brain damage,” Sallie Baxendale, a professor of clinical neuropsychology at University College London, tells Inverse. “Anything that happens in their life after that is unlikely to be retained for longer than a few hours, or even shorter in most cases.”

In many ways, Memento’s depiction of anterograde amnesia is actually quite accurate. But in real life, coping with short-term memory loss typically looks a lot different than covering your body in tattoos and resorting to a stack of Polaroids to make sense of things.

How to Lose Your Memory

Anterograde amnesia doesn’t happen spontaneously but rather occurs after someone experiences severe damage to the brain. Infections, head trauma, heavy drinking, and complications from other neurological conditions or surgery can bring on this type of memory loss.

Hans Markowitsch, a neuropsychologist at Bielefeld University, tells Inverse that anterograde amnesia is like being frozen in time, “able to remember [the] past and retrieve it, but unable to add new information.”

One thing that makes Leonard’s case unique is that he appears to be struggling only with anterograde amnesia, and nothing else. Richard Allen, a professor of psychology at the University of Leeds, tells Inverse that most patients with the condition typically have other impairments as well.

“A pure case of [anterograde amnesia] in an otherwise high-functioning patient, as depicted by the character Leonard, would be relatively rare,” Allen says. Instead, most cases of anterograde amnesia are typically coupled with difficulties in attention, executive control, action, language, and other types of memory loss.

And unlike Leonard, who spends his days traveling around town trying to hunt down his wife’s killer, many patients with anterograde amnesia require stationary, around-the-clock care.

“Care is normally aimed at just reducing the confusion a person with anterograde amnesia experiences by keeping them oriented to time and place,” Baxendale says. And many are unable to live independently, requiring external aids and the help of caretakers, Allen explains.

Many of Leonard’s habits would only lead to more confusion for a patient with anterograde amnesia. Hence why viewers see over and over again in Memento just how easy it is for him to make mistakes and struggle to retain information.

Coping with loss

Let’s talk about Leonard’s stack of Polaroids — the fragments of people and places that he keeps with him to remember what happened in days past. This is a strategy known as cognitive offloading, which can be helpful for people with memory loss.

Jotting down notes, using wearable cameras that automatically take photos, and storing information in a smartphone have all been explored in studies as viable tools for people with memory loss. Allen cites a recent case study where a young patient with anterograde amnesia successfully relied on phone apps to store information in lieu of remembering details about their day.

Labeling items, such as expiration dates for food, can also be a helpful way to retain information, Elizabeth Kensinger, a professor of psychology at Boston College tells Inverse. But there are limitations when a person relies on notes, photographs, and lists to record information.

“More elaborate uses of mnemonic devices can often fail to be useful, because they tend to rely on memory,” Kensinger says. “For instance, a stack of photographs is only useful if the person remembers to look at them.”

And the fragmented information that Leonard puts on his body and on the backs of Polaroids can make it difficult for him to remember the truth about his recent past.

Truth and fiction

In addition to Shelby’s deficits in forming new memories, his recollection of the distant past isn’t exactly accurate, either. That could be attributed to his condition, since it’s common for anterograde amnesia to happen in tandem with retrograde amnesia.

But it could also be due to psychological damage, rather than neurological. Memory loss and distortion can stem from psychological traumas. Plus, it’s just plain common for people to remember things incorrectly.

“Our memories aren't an objective CCTV of past events that we can just replay,” Baxendale says. “Every time we retrieve a memory, it is put back in a slightly different place and changed in different ways. Strong psychological factors can rewrite memories completely.”

Shelby tells many stories about a character named Sammy Jankis, a retired accountant with amnesia whom he met during his days as an insurance agent. But at the end of the film, it’s revealed that Shelby is Jankis, and that he projected his own story onto Jankis in his memory.

That realization also means that Shelby’s wife was never murdered. Rather, Shelby gave her too many insulin injections for her diabetes, killing her as a result.

There’s a subtle scene halfway through Memento that hints at this truth, and also gives a snapshot into what life is often like with anterograde amnesia. Shelby tells a story about Jankis, and viewers see him seated in a chair at a care facility in a hospital. For a split second, Jankis is swapped out with Shelby, foreshadowing his true identity.

“Blink and you miss it, but it hints at the real state of dependency that anterograde amnesia leads to,” Baxendale says.