This is part of a series on the theme of whistleblower Reality Winner.

News of South Texas native Reality Winner is on the rise. Last month, it was the stage-to-film adaptation Reality receiving high praise at its Berlinale world premiere, leading HBO Films to acquire rights for a release expected no later than May. By year’s end, it’s the arrival of the Codebreaker Films documentary, United States vs. Reality Winner. Meanwhile, production has already wrapped on the dark comedy Winner. Headlines keep coming.

All the publicity will surely encourage supporters of the whistleblower known—and convicted—for leaking top-secret evidence of Kremlin hackers targeting the 2016 elections. But just this past December, the New York Times painted a less-than-celebratory picture.

The Times portrayed an understandably despondent Winner, now 31, on parole-like supervised release at her family’s Kingsville home, lamenting how, as a result of her leak, nothing changed, an outcome she found even worse than her prison term—five years, three months—the longest sentence ever imposed on a civilian defendant for unauthorized disclosure of national defense information to the media. The onetime linguist for a National Security Agency contractor told the paper her pain stems from “knowing that you really didn’t change anything. Nobody cares.”

Yet the classified NSA report she snail-mailed to the Intercept in 2017 remains more relevant than typically realized. The five pages—buttressed by several corroborations that surfaced after their publication—detail a multi-stage Russian military intelligence campaign to trick county elections departments into compromising their computers only a week before Election Day 2016. The operation revolved around two distinct phases of spear phishing, a common cybersecurity threat: personalized emails mimicking legitimate ones, containing potentially harmful hyperlinks or other enticing traps, generally sent in hopes of fooling targets into betraying confidential information such as their sign-in credentials.

The leaked document reveals how, if the Moscow hackers, posing as Google in spear phishing emails, were able to breach Tallahassee-based VR Systems in August 2016 (as the report considers “likely”), the Russian military unit probably next remotely snooped around for ways to better impersonate the voting equipment vendor. Come November, this time pretending to be VR Systems, they emailed what looked like new instructions for the company’s electronic pollbooks—complete with the supplier’s red-and-blue logo—to 122 local elections officials. If opened, the Microsoft Word attachments promising benign guidance on e-pollbook configuration would quietly download, from an online server the hackers controlled, further malicious computer code, “very likely” with the goal of surveying the victimized networks or affording the distant attackers ongoing access.

There Winner’s disclosure ends, yet the ripple effect she set into motion encompasses a great deal more, still significant as campaign cycles recur and election technology vendors seek to expand their customer bases, including in her home state, where a little over a year ago the Secretary of State’s office certified VR Systems e-pollbooks for use in elections. Two local elections administrators and a county information security officer in Texas gave us their thoughts on the controversial company’s arrival in the Lone Star State market when the Texas Observer asked about the cyberattacks Winner divulged; the landscape they describe shows in the background local officials, often underresourced, contending with world-historic forces while in the foreground balloters, at times unaware of electoral system mechanics and sword crossings, collect “I Voted” stickers like participation trophies.

Although the whistleblower herself has previously addressed her motives and the country’s extreme polarization around election integrity, her own ability to speak out is legally limited. Her mother Billie J. Winner-Davis, a dedicated advocate for her daughter, told us, “When Reality first started her supervised release, her probation officer said ‘Don’t do interviews,’ and she said, ‘That’s not part of my plea deal.’ She’s done interviews and has to let them know—and their basic response to her was Don’t do interviews. She does have a new probation officer, and it’s a little easier for Reality to communicate back and forth with this one. But she has to be cautious: She can’t talk about anything that has to do with her case.”

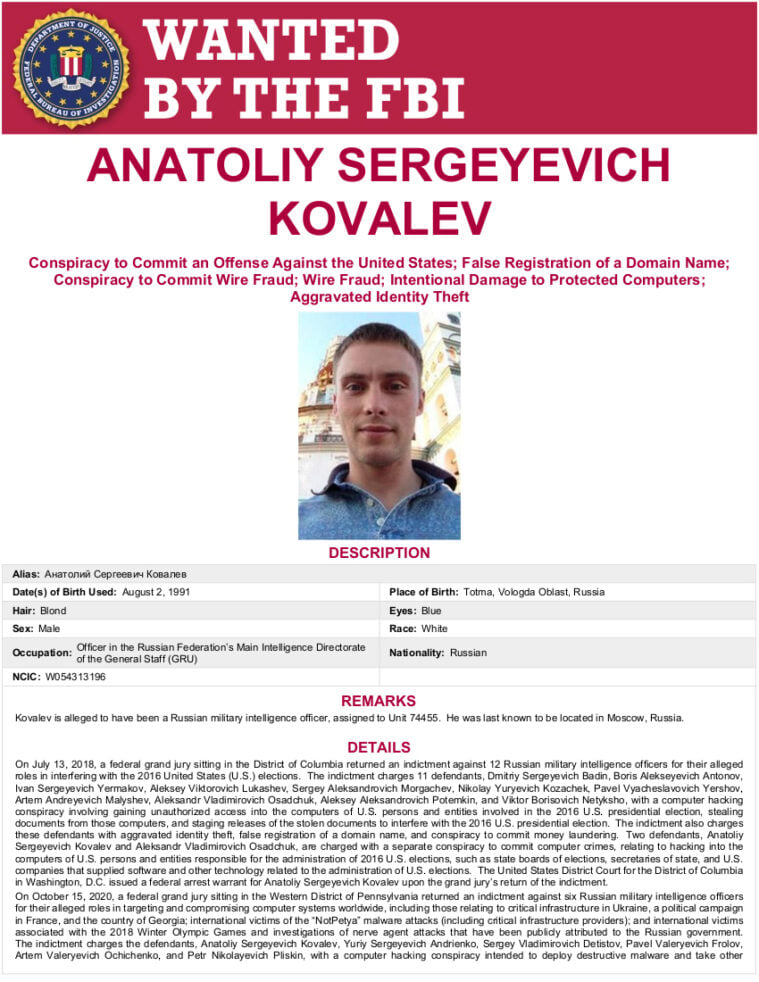

Official secrecy obscures precisely what happened following the events detailed in the NSA report, but the public interest generated in part by Winner’s sacrifice assuredly prodded erstwhile Special Counsel Robert Mueller to formally accuse Russian military intelligence members of crimes matching—and exceeding—those depicted in the top-secret document. In 2018, Mueller indicted Anatoliy Sergeyevich Kovalev and his commander Aleksandr Vladimirovich Osadchuk for, among other cyberattacks, having “hacked into the computers of” an unnamed elections vendor whose description tracks with that of VR Systems. A year later, in his landmark report to Congress on the Vladimir Putin regime’s 2016 election interference, Mueller surprisingly said the Russian unit had installed malicious (and otherwise undescribed) software on VR Systems’ network.

Mueller stated, too, that the Kremlin hackers targeted “over 120 email accounts” belonging to local elections officials—a reference to the second round of spear phishing emails, the ones disguised as VR Systems e-pollbook instructions—in the battleground state of Florida, where the computer network of at least one county elections department was, he said, indeed intruded on. The bogus missives, in other words, actually duped a local Florida voting official, and maybe duped more than one.

Roughly halfway through former President Donald Trump’s term, three top Florida leaders addressed the matter due to information about the Russian cyber espionage operation slowly trickling out aided by Winner having busted up the dam. Like Mueller, they said Moscow’s military officers had penetrated Florida county election systems in 2016—but then spoke of further subterfuge. Governor Ron DeSantis said it was two counties victimized because “someone clicked on” the spear phishing trickery. U.S. senators for the state Bill Nelson and Marco Rubio even warned that the hackers could meddle with voter rolls.

Although none of the three Sunshine State politicians went so far as to say Russian military intelligence took advantage of their county department breaches to modify voter data, each refused to elaborate—because the briefings they’d attended were classified, with the governor signing an unusual nondisclosure agreement with the FBI. With the exception of Illinois, the Senate intelligence committee, in their underexamined three-year investigation of the 2016 Kremlin interference, similarly left unnamed the small number of states whose voter rolls the panel concluded, in May 2018, that Moscow hackers had accessed.

Then in 2020, journalist Bob Woodward reported the most fearsome feat from this cyberattack campaign yet described: According to the NSA and CIA, Putin’s hackers had planted sophisticated, though never activated, malicious software within elections departments of at least two Florida counties—St. Lucie and Washington—surreptitious computer code able to selectively manipulate voter eligibility based on demographics. Sizably altering eligibility would probably sow Election Day confusion and distrust; partisanly deregistering individuals would likely lead to fewer votes cast for candidates disfavored by the machinators.

Despite the Kremlin’s hacking spree, the Texas Secretary of State’s office in January 2022 approved VR Systems to join six other certified vendors the 254 counties can pick from for pollbook devices, which precinct workers use to check in prospective voters. VR Systems CEO Mindy Perkins told us no Texas county has adopted their e-pollbooks. Yet.

Perkins said in an email that two counties, Denton and Young, do employ the company’s flagship Voter Focus elections management product, certified by the Texas Secretary of State’s office in June 2020. Among other features such as designing ballots and handling poll worker payroll, Voter Focus manages a county’s voter registration database, interfacing with the statewide one. It can also work with e-pollbooks, those of VR Systems or those of rivals.

Young County Elections Administrator Kaitlyn Mosley told us her office, where in August 2020 Voter Focus first went live in Texas, ceased using the product in late February and resumed using simply the website for the statewide database, a system known as Texas Election Administration Management (TEAM). Mosley explained that her previous good experience with TEAM as a Jack County clerk, her tiny department’s need to save money, and a desire to keep Texas elections in Texas—rather than contract with VR Systems a thousand miles away—were behind the decision.

When asked if reports of the 2016 Russian military intelligence operation against VR Systems played a role in Young County abandoning Voter Focus, Mosley said she hadn’t heard of those cyberattacks or of Reality Winner—but wanted to learn more.

Mosley told us that, setting aside outsourcing for major projects, she has a single information technology helper, a floater in the courthouse where her office is. “I have like one person,” she said, “who will come and help me change out cables and make sure my emails open right and all that.”

Calling for federal regulation of elections, Senator Ron Wyden, in the first volume of the Senate intelligence committee report on the 2016 Kremlin interference, highlighted the absurdity of expecting “a county election IT employee to fight a war against the full capabilities and vast resources of Russia’s cyber army.”

“That approach failed in 2016,” Wyden warned in the 2019 report, “and it will fail again.”

Unlike Young, the much more populous Denton County has an official IT department, where Todd Landrum is in charge of all county cybersecurity. “We take security, especially spear phishing—and phishing in general—extremely seriously,” he told the Observer.” By state law, we have to do mandatory training, but we take that above and beyond with supplemental training. I can’t divulge exactly what we do, as that would weaken our defenses, but if it’s done as an industry standard, we do it.”

“We take security, especially spear phishing—and phishing in general—extremely seriously.”

Asked about the Kremlin hackers in 2016 putting substantial effort into tailoring spear phishing messages to imitate VR Systems e-pollbook instructions, Landrum told us such cyberattacks happen in every industry. “The big difference between …” he said, and stopped. “Well, I can’t talk about that.”

Denton County Elections Administrator Frank Phillips said he’s happy with VR Systems and Voter Focus, which his department, a floor below Landrum’s, began using in August 2022. Phillips said his office has seen the product’s advantages for mapping balloters with Geographic Information Systems integration rather than by relying on street ranges, making “redistricting efforts much faster and more accurate.”

“We plan on staying with Voter Focus,” Phillips told the Observer.

What about the 2016 Kremlin cyberattacks? Phillips replied, “I spoke with VR Systems many years ago (long before we became a customer) and am satisfied that there was no intrusion by outside actors.” That’s been the vendor’s staunch position.

VR Systems has long maintained that Moscow in 2016 only tried to intrude on their network with spear phishing emails camouflaged as Google alerts—and that the company’s employees never fell for it, the hackers never broke in.

“We disagree with the Special Counsel [Mueller] report,” Perkins told us. If the Kremlin hackers obtained e-pollbook technical data, she said, or email addresses for Florida local officials, then they must have done so from sources not including the vendor’s network, such as search engines turning up publicly available county contact information. No one has revealed the 122 email addresses the NSA report references, however; maybe the Putin regime military unit targeted back-of-house ones.

To support its stance, VR Systems has repeatedly cited as exonerative multiple but belated forensics investigations. As with earlier company responses to this same request by others, among them Senator Wyden, Perkins refused to share the forensics reports with the Observer. Not even in part. In 2019, Wyden accused the business of “stonewalling Congressional oversight.”

Aside from VR Systems’ own internal review, the top-dog cybersecurity firm FireEye, today called Trellix, and the Department of Homeland Security separately conducted the purportedly exculpatory forensics studies, except not until after the Intercept published Winner’s leak—months and months past the cyberattacks, likely enough time for evidence to dry up on whichever systems the company allowed the outside investigators to scrutinize.

Then, in massive months-long cyber espionage offensives between 2019 and 2020, both Homeland Security and FireEye were themselves hacked by the Kremlin.

Should Texans worry over the possibility that counties will adopt the controversial supplier’s e-pollbooks or Voter Focus? After all, though questions and common cybersecurity concerns linger, no one has proven the Russian military unit altered voter registration data or vote totals, and no one has shown VR Systems products bear any unique flaws making it easier for faraway hackers to misrepresent them specifically as opposed to those of any other vendors. So what’s the bottom line?

To understand the impact VR Systems may have on the Lone Star State requires reviewing the ripple effect of Reality Winner’s whistleblowing in swing state North Carolina and elsewhere, the country’s patchwork elections system in general—plus voter registration in particular—and most of all, the improvements recommended by bottom-up activists appealing to any who do care and do want to change contemporary voting, the recently shaken foundation of democracy, for the better.

Reality Winner, however, cannot easily share her thoughts.

As audiences await the forthcoming films about Winner, the whistleblower herself may not openly discuss some of her story’s most important and most sensitive aspects, for fear of retaliation from the Office of Probation and Pretrial Service, under whose watchful eyes she must live for another 20 months or so. Like her supervised release conditions, her plea deal limits her speech, as do burdensome, lifelong prepublication review requirements resulting from her military career and her time as one of the rank-and-file millions making up the multibillion-dollar, shadowy U.S. spy agency system.

The restrictions prohibit Winner from directly commenting on the NSA report, but exactly what else is forbidden can quickly become a murky question—including to what extent she can elaborate on her reasons for leaking the document.

It’s a plight sadly familiar from other national security whistleblower trials: Winner’s felony charge under the century-old Espionage Act blocked her from mounting a public interest defense in court, even though she gained not a single penny from her deed.

Clarifying her motive, the whistleblower initially spoke out—apart from her brief allocution at sentencing—when toward the end of 2021, on supervised release, she talked with “60 Minutes.”

“The public was being lied to,” Winner told a national audience. “I just wanted to end the media spin” to that “really big question mark happening about midway through 2017.”

Did the Putin regime actually hack the 2016 elections for Trump? Is his presidency illegitimate?

“I thought this was the truth,” she said, explaining what she would have told her judge had she been allowed. “But also, [this] did not betray our sources and methods. Did not cause damage. Did not put lives on the line. It only filled in a question mark that was tearing our country in half in May 2017.”

Winner printed the NSA report, authored in May 2017, on the 9th of that month, the fateful day Trump fired James Comey, then the holdover FBI director from the administration of former President Barack Obama running the investigation into the new president’s ties with the dictator Putin. Winner dropped the pages, enclosed in an envelope sans return address, into a U.S. Postal Service mailbox soon after.

A few months earlier, in January 2017, U.S. spy agencies had completed a formal assessment, ordered by the outgoing Obama, that found the Kremlin in 2016 had aimed to hurt Hillary Clinton’s electability and help Trump’s—but every page of the declassified version acknowledged omitting “the full supporting information.”

The ex cathedra assessment devoted fewer than 100 words to Moscow’s cyberattacks on state and local elections boards, and expected, rather than earned, trust, in providing minimal in-depth proof for the security clearance-lacking laity, so it is no wonder many sat on the fence about Trump and Russia or got sucked into the gravity well of online Kremlin propaganda—until Winner’s evidence-rich leak, with its doubt-dispelling raw data such as software version numbers, hash values, exact email addresses and file names, and more leapt onto center stage, at least for a few news blips.

Speaking with the Broadway Podcast Network for an episode aired in January, Winner explained what she hoped readers would gain from the top-secret report. “What I had intended was for this document to be a litmus test for people to look at their media more critically. It wasn’t, like, this anti-Trump temper tantrum. It was, What if the American people were to see one set of facts in black and white on a piece of paper, see what the opposition media is deciding to pull from that piece of paper, but also what their media is deciding to pull from that piece of paper. And it was supposed to kind of, break the glass, this spell that partisan media had over the country in 2017.”

“It was supposed to kind of, break the glass, this spell that partisan media had over the country.”

The whistleblower continued: “That’s what I thought would happen and unfortunately the media disappointed me even further by taking the lowest-hanging fruit, which is the scandal of who Reality Winner is, and how weird her name is,” and other personality-centered minutiae. “That’s what the media focused on and that’s why they moved on so fast, that’s why this wasn’t regarded as a case in which the character of our nation was on trial.”

VR Systems electronic pollbooks arriving in the Texas market comes at a severely polarized time when, acknowledged or not, national and international conflicts and crises, as well as their associated propaganda, loom over the mundane election administration tasks of local departments, even in little rural counties like Young.

Moreover, examining vulnerabilities of voting technology might seem unpalatable in the wake of the prior president’s “Big Lie” election denialism. Following Election Day 2020, Trump became the first president in U.S. history to try to illegally overturn an election after losing it, an attempted auto-coup.

In December, the bipartisan January 6 Committee determined the demagogue, alongside additional wrongdoings, “unlawfully pressured State officials and legislators to change the results” and that his “false allegations that the election was stolen” summoned “tens of thousands of supporters” to Washington, D.C., where Trump encouraged their armed and violent attack on the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021. The committee recommended the Justice Department bring four criminal charges against this particular personification of impunity, who presently faces a handful of criminal investigations yet has long escaped indictment in the judicial system for even a single crime, though that may soon change—if so, Trump would become the first U.S. president, former or sitting, to be formally accused by domestic prosecutors in court, ever.

Twice-impeached Trump, currently campaigning for a return to the White House, and his allies filed dozens of lawsuits aimed at toppling or at least tarnishing Joe Biden’s victory—and not only have they failed in all save one minor case, but also, in some instances, federal judges delivered scathing criticism and sanctions to Trumper lawyers for their evidence-free approach to rules of evidence, notably their reliance on mere assertions that rigging was possible. For example, in King v. Whitmar, Judge Linda Parker concluded the plaintiffs’ counsel “abused” the litigation process by “proffering claims not backed by evidence,” directed the attorneys to pay fees, and mandated they undertake remedial legal education on pleading standards and election law.

Besides providing a similar analysis of the scores of unsuccessful ‘Stop the Steal’ lawsuits in their July 2022 report, Lost, Not Stolen: The Conservative Case that Trump Lost and Biden Won the 2020 Presidential Election, eight prominent right-wing lawyers, former U.S. senators, and retired federal judges hinted that Trump’s team cared less about winning lawsuits and more about leveraging them to fuel sound bites: “In many cases, after making extravagant claims of wrongdoing, Trump’s legal representatives showed up in court or state proceedings empty-handed, and then returned to their rallies and media campaigns to repeat the same unsupported claims.”

Knowing the importance of the mass media-ified battle for hearts and minds, Obama tried, from the bully pulpit in October 2016, to counter candidate Trump’s baseless claims of a fixed presidential race—unusual and shocking for a top contender to profess—by declaiming that “there is no serious person out there who would suggest somehow that you could even rig America’s elections.”

Yet for rational reasons, serious higher-ups in or aligned with Obama’s own party made exactly that serious suggestion: Elections in this very country might be manipulated unfairly. A federal judge he appointed wrote, in a 2018 ruling quoting criticism of a state legislature for onesidedly redrawing maps, that extreme partisan gerrymandering “amounts to ‘rigging elections.'” In the 2019 Senate intelligence report, Wyden wrote “the lack of relevant data precludes attributing any significant weight” to the rest of the panel’s finding of no evidence for the Putin regime having modified voter rolls or vote counts, thereby implying he couldn’t rule out rigging by the distant hackers.

Such examples have precedent—since passage of 2002’s Help America Vote Act, which greatly accelerated computerization of elections, civil society has repeatedly warned of myriad rigging risks. More than 300 voting computer incidents were reported to hotlines in 2010, over 70 for 2020, everything from broken devices to incomplete ballots to unexplained glitches. Without delving into analog election fraud methods, if there are no agreed smoking guns exposing top-down digital rigging—nor guilty verdicts—there certainly are smoldering guns involving touchscreens switching votes lopsidedly and suspicious memory card error. Because so much evidence is proprietary, largely off limits to open inspection, experts are usually left to puzzle out patterns, such as statistical disparities between exit polls and final tallies, that are tough to transform into viral gotchas.

Speculative harms are insufficient for legal standing in courtrooms—as federal judges forcefully reminded Trumper lawyers—yet efforts by Obama and other influential voices to push the sheer possibility of malevolent thumbs on electoral scales outside the bounds of respectable thought cede the topic to anyone with a platform, regardless of their motives or analytical skills, in favor of rose-tinted glasses and shutting mouth and mind.

The hard evidence heft of Reality Winner’s top-secret divulgence helped convert the subject matter to fair game. Voting system vulnerabilities were once much farther off the table of so-called serious discussion than they are presently. Today, relevant entities such as Homeland Security, under which the Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency formed in 2018, have become slightly more responsive to public interest, as if there’s been at least some small recognition that election system hierarchs demanding faith and trying to sweep problems under the rug backfires, especially when computer security trainwrecks fill the news on the daily. Battles for narrative control go on.

Last month, the Associated Press said “[h]igh-profile problems” with electronic pollbooks “opened the door for those peddling election conspiracies,” but also represent “significant security challenges,” which “raises concerns going into 2024.”

The subject necessitates careful investigation—falling into neither groundless MAGA blarings nor the opposite everything’s fine, nothing to see here-style denialism—and that, in terms of grassroots activism, VR Systems, Texas, and beyond, must wait until our series continues.

But in the meantime, Reality Winner’s lawyer, Alison Grinter, told the Observer how she thinks people can fight for the whistleblower: “I think it’s very important that we take a public stance reclaiming our elections and point out that foreign interference won’t be tolerated and Putin does not have friends on the inside anymore. Because she was overcharged and unfairly treated for political reasons, I think that a big first step in that direction would be a pardon for Reality Winner.”