In 1938, a group of feminist agitators came together in London to tackle what they saw as the most pressing issue of their time: inequality in marriage. For the Married Women’s Association, the right to vote – won for women over 30 in 1918 – was just the beginning of women’s emancipation. The legal status of housewives was next.

If you were a married woman in the early 20th century, you had no rights in your home, nor in the housekeeping money your husband gave you, nor even in the bed you slept in, unless you had used your own money to buy it.

You were also paid less than men, while all the work in the home was exclusively your domain and was unpaid. Your husband, by contrast, would be paid an inflated income to support his dependants, termed a “family wage”, to which, ironically, you had no rights to whatsoever. In the eyes of the law, you were essentially invisible.

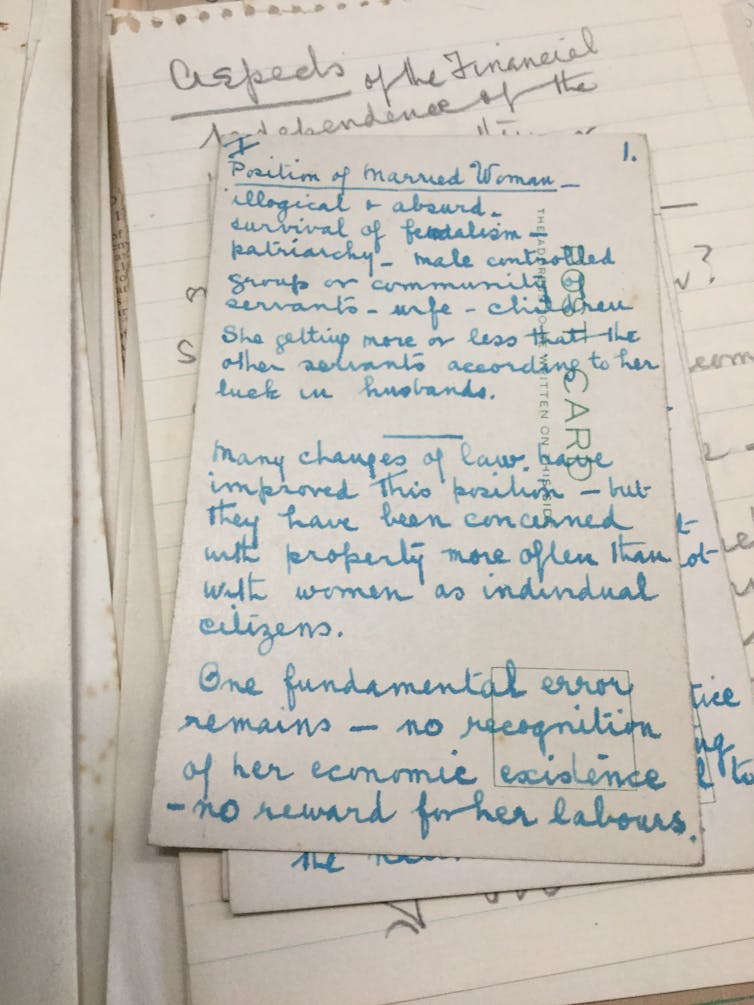

The Married Women’s Association sought to use the law to address the poverty women faced in relationships. As the association’s founder Juanita Frances put it:

I’m not asking for protection, I’m asking for legal rights in hard cash.

These women’s story has long been overlooked. As I show in my new book, Quiet Revolutionaries (and accompanying podcast), what they were fighting for remains highly topical.

For the first time in at least 30 years, an increasing number of women are leaving employment to look after the family. This is hitting their career growth, their income potential and their pensions. Women are bearing the brunt of the spiralling cost of childcare in the UK, which the cost of living crisis is only likely to worsen. In the absence of better state support, the question – as it was for women in the 1930s – is whether there is anything the law can do.

Birth of the Married Women’s Association

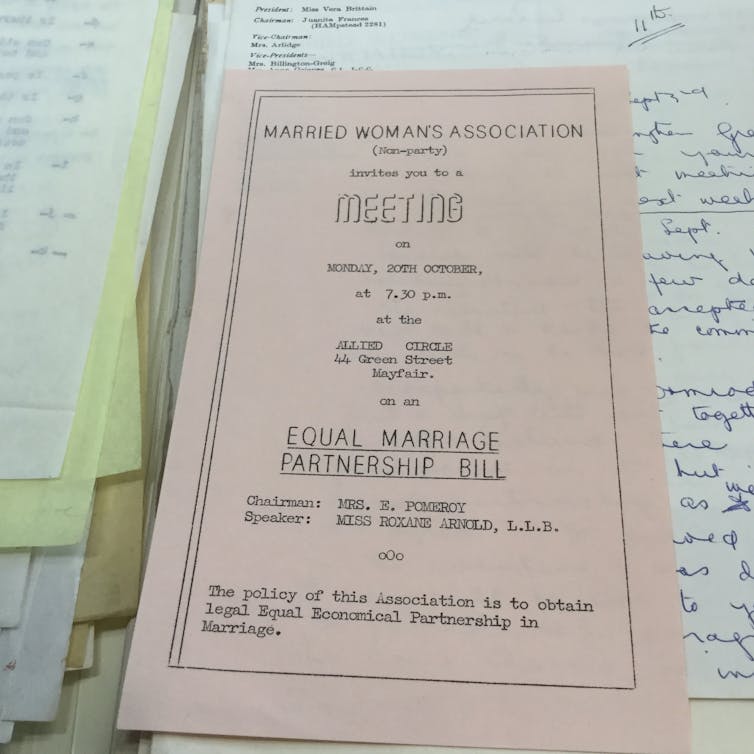

I have done extensive archival research in the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics, where the association’s papers are held. The idea to form the group came from Dorothy Evans, a former militant suffragette.

Evans was lesbian and personally opposed to marriage. However, she saw reforming marriage as key to women’s emancipation. She contended that failing to recognise the value of housewives’ work, in the same way men’s work outside the home was, affected the lives of all women.

Evans recognised the leadership potential of Juanita Frances, a former nurse, burlesque dancer and conjurer’s assistant. Frances was new to the feminist movement and keen to make a difference. “How have I missed this all my life?” she would say of her involvement years later in an interview in 1986. She recalled: “I came bang into the feminist movement and it amazed me.”

The association had several prominent members. As well as being the association’s first president, Edith Summerskill was a doctor who was active in the establishment of the NHS, an MP, and the first woman to call herself a feminist in parliament.

The authors Vera Brittain and Dora Russell played important roles in the association, as did the pioneering lawyer Helena Normanton, the first woman to practise as a barrister and one of the first two women to be named King’s Counsel. Doreen Stephens’s involvement, meanwhile, was instrumental in her going on to become the first female BBC executive.

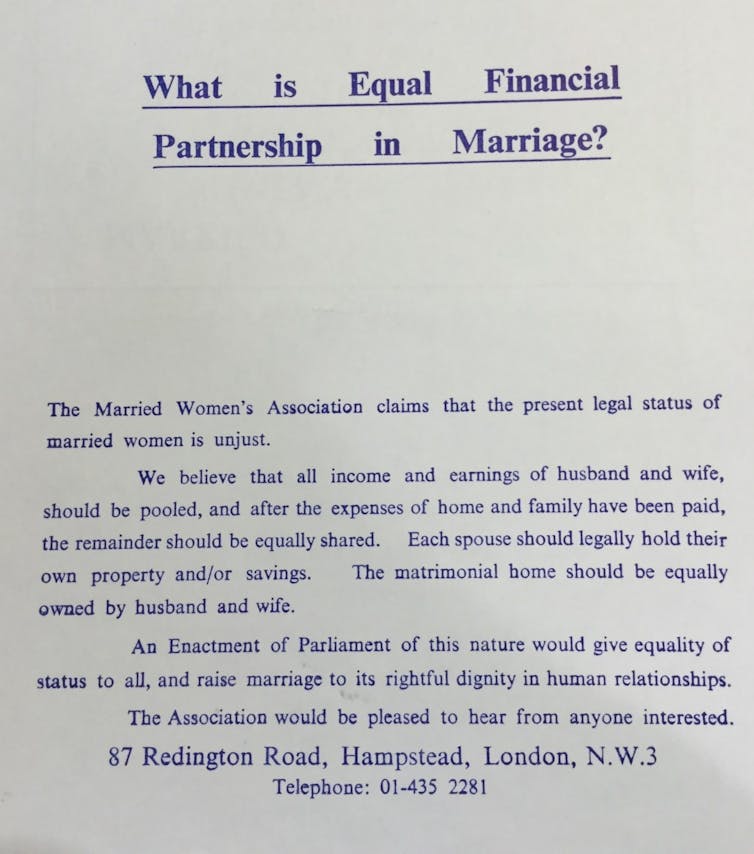

Their ideas were as radical as their CVs suggest. They argued that because men could not go out to work without their wives looking after the home and children, the wives should be entitled to share the husband’s property. The domestic and caregiving work they were largely responsible for made an undeniable contribution to the family’s wealth.

Reforming family law

To have this recognised, the association proposed a new marriage law. This legislation would give married women a legal right in their spouse’s property during marriage and a right to know what he earned.

Ultimately, the association could not get its new marriage law enacted. Its proposals were viewed as too extreme. For many, the law focusing on the rights of married women was akin to interfering in the private world of the home. An article in a 1952 edition of the Daily Mirror characterised these women as threatening man haters:

‘The Married Women’s Association!’ How it rolls off the tongue like a peal of distant thunder! The sound of it is deep and ominous. Even the sight of the four words in type looks like the iron-maw of a fifteen inch gun – menacing, resolute, implacable.

Nonetheless, the association wrought considerable influence in terms of wider family law. While their ambition of equal partnership was revolutionary, their methods were quiet, yet persistent.

Association members worked behind the scenes to make it easier for women to enforce maintenance after divorce when husbands refused to pay it. They were instrumental in getting the Married Women’s Property Act 1964 enacted, which saw wives given the right to a one-half share in housekeeping savings.

They also helped Summerskill secure the right for deserted wives to stay in their home via her Matrimonial Homes Act 1967. And they pressurised the government into introducing the Matrimonial Proceedings And Property Act 1970. This law, still in force as part of the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 today, gave the homemaking spouse rights in property on divorce.

The fight goes on

The status of women has changed unrecognisably since the early days of the association. The broader problems of gender inequality, however, endure.

Research shows mothers are still more likely to make career sacrifices than fathers. Women take longer than men to recover financially when their marriage has broken down. And the issue of pension provision can also create significant financial inequalities between spouses.

Dismissing these statistics as simply reflecting women’s “choice” becomes difficult when the price of childcare rises to the extent that employment reaps little financial gain.

In the last 12 months in the UK, the number of women aged 25-34 not in work has risen by 13%. And with childcare costs strikingly higher than almost everywhere else in Europe, mothers increasingly cannot afford to return to work.

Though caregiving is an often marginalised, female experience, some men are, of course, making these sacrifices too. However, until these contributions are valued in law, as the Married Women’s Association argued more than half a century ago, the ambition of equal partnership in marriage cannot be realised. In failing to value women’s work in the home, we are still failing women.

Sharon Thompson received funding from the Socio-Legal Studies Association to undertake the research referred to in this article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.