There are sequels and then there are movies which argue that sequels are ridiculous and that we’re all fools for playing Hollywood’s game. Or, at least, there is one such movie. Gremlins 2: The New Batch, which marks its 30th anniversary on 15 June, is a subversive farce that jams its finger in the eye of cinema convention and blows its nose in the face of Tinseltown avarice.

Gremlins 2 is a sequel that understands that it exists for no reason other than to line the pockets of the studio. And it wants you to know that it knows. Moreover, as with all truly great films, it can be appreciated at several levels. It succeeds as meta commentary on Hollywood greed. But it also features a scene in which one of the titular green goblins with chihuahua ears and googly eyes is noisily mulched in an office shredder. It’s got the power and the gory.

“After several years of trying to figure out how to make a sequel to this movie that really didn’t need a sequel, my producer, Mike Finnell, and I were convinced to come back,” is how director Joe Dante described the process of making Gremlins 2 to the Chicago Reader in 2012. “We decided to do a movie that not only made fun of the first movie and all those horror movie tropes, but got away with some social satire as well.”

“Made fun of” is an understatement. The big idea is that the ghastly gremlins, having terrorised a small American town in the original 1984 film, have now been unleashed upon a New York skyscraper. The building is the egotistical brainchild of a buffoonish tycoon with oodles of bluster and the best hair. So, yes, it also functions as a Donald Trump parody decades before the world knew it needed a Donald Trump parody.

One of the earliest victims of the freshly spawned green meanies is Leonard Maltin, a film critic who took a vocal dislike to the original Gremlins. We see him filming a Barry Norman-style segment for a show called “The Movie Police” in a studio in the skyscraper. He holds up a VHS copy of Gremlins.

“I know some people found this movie fun,” Maltin begins. “But me… I’d rather spend two hours having root canal done. What’s fun about having ugly, slimy, mean-spirited gloomy little monsters run amok and attack innocent people. Are movie-goers so desperate for entertainment?”

His pontifications turn to gasps. Three of the rubbery wretches have emerged from behind a couch, looping a reel of celluloid around his neck. He screams. Dante cuts to a gremlinstest card. What have you just watched?

At another point a character comments on the absurdity of the gremlin “rules” that were a lynchpin of the first film. To prevent the cutesy mogwai from morphing into gremlins, it is forbidden to feed them after midnight. But what if a mogwai has a piece of food stuck in its teeth – which then falls lose and is swallowed after midnight? Does that count? Imagine a Star Wars movie in which two Jedi Knights count the ways in which the Force is made-up nonsense.

Most daring of all, however, is the sequence – widely admired but never emulated – in which Gremlins 2 drives a bulldozer through the “fourth wall” separating art and audience.

As terrified office workers flee the monster infestation, the screen shudders, turns scratchy and is suddenly filled with gremlin shadows. They are in the cinema projection booth, mucking up their own blockbuster.

They continue to do so until wrestling star Hulk Hogan stands up in the audience and shouts at them to calm down so that we can go back to watching the feature presentation. Three decades later, the segment still scrambles your brain. Are films even allowed to do this?

Dante was a B-movie guy from Livingston, New Jersey, who, as with Francis Ford Coppola and James Cameron before him, had apprenticed with exploitation master Roger Corman. Later, he brought an irreverent touch to splatter-fests Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981). The former was a giddy Jaws rip-off that came to the attention of Steven Spielberg, who loved it. So he hired Dante to direct the third segment of the Twilight Zone anthology movie he was producing in 1982.

A great deal went wrong with that film – most notoriously a helicopter crash at Indian Dunes ranch in California in which two children and actor Vic Morrow died. Still, Dante impressed Spielberg and a year later his new acolyte was put in charge of Gremlins, a gonzo romp about vicious latex beasties running amok in fictional Kingston Falls in New York State.

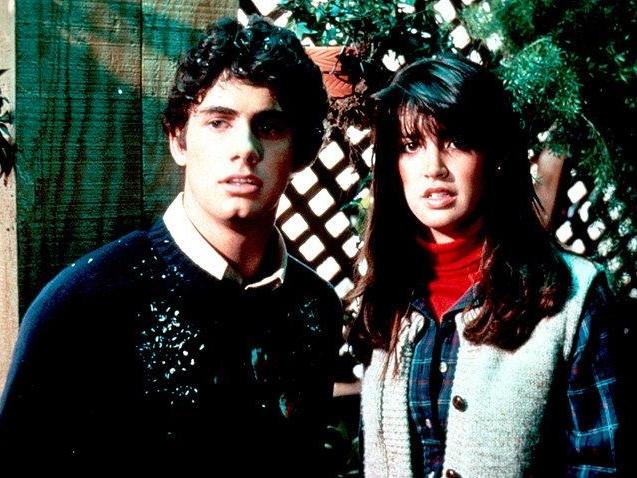

Warner Brothers had been thumpingly lukewarm about Gremlins. The film, which starred the relatively unknown Phoebe Cates and the completely obscure Zach Galligan, really only got made because Spielberg’s production company, Amblin Entertainment, was keen on it. To the surprise of almost everyone involved it proved a massive hit, however, earning more than $200m on an $11m budget.

As the box office tills chimed out a jolly tune, Warner executives decided that, actually, they loved the gremlins – and wanted more of them. But the director had had enough. Making the film had been an endless battle of attrition. The rubber puppets posed new challenges on a daily basis. Warner suits pushed constantly to cut the budget. Did Dante want go to back into that inferno? Thanks but no thanks.

He went on to direct Explorers, Innerspace and the Tom Hanks/Carrie Fisher misfire The ’Burbs. Gremlins had an equally hot streak through the Eighties as it became a huge hit all over again on VHS. Even the official novelisation, by future Harry Potter director Chris Columbus, was a smash. The potential for a Gremlins 2 was obvious.

Still, as one of Spielberg’s most astute proteges, Dante understood that, from a filmmaking perspective, sequels were a mug’s game. Spielberg had refused to be involved with Jaws 2 and, after some spitballing, shot down an ET sequel.

But Dante was also smart enough to understand he wasn’t the second coming of Spielberg, and that he couldn’t afford to be as picky as his mentor. So, after years of pleading by Warner Brothers, he caved in. He would make Gremlins 2 – on the proviso that he receive complete artistic freedom.

His big idea was that Gremlins 2 would call attention to the absurdity of its own existence. Gremlins had been a self-contained classic. Artistically speaking, there was no justification for a follow-up.

Fine, whatever, said the studio. So long as Gremlins 2 featured Cates and Galligan and hordes of gibbering emerald monstrosities, Dante could do as he wished. That was their pledge and goodness did he hold them to it.

The first component of the original Gremlins that Dante threw overboard was the setting. In place of the It’s A Wonderful Life-esque milieu of Kingston Falls, Dante, producer Fennell and writer Charles S Haas relocated the franchise to the corporate New York of Gordon Gecko’s Wall Street and Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Gremlins, which was very loosely inspired by a 1943 Roald Dahl novella, had started with failed inventor Randall Peltzer visiting a Chinatown curiosity shop. There, he attempts to acquire a furry mogwai named Gizmo as a gift for his son, Billy. Mr Wing, the owner refuses, but his grandson slips Peltzer the magic fur ball. This, of course, is a poppet with strings attached. And when Billy flouts the rules of mogwai ownership, Gizmo spawns a plague of gremlins.

Second time out, the action begins back at the store of the now terminally unwell Mr Wing. A New York tycoon with wonderful hair – really, it’s fantastic – tries to buy him out. Wing says “no”. But he passes away a few weeks later. With that, a wrecking ball slams through the front door.

Fleeing, the terrified Gizmo is spotted by two scientists Dean and Lewis (named for Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis) working for the millionaire and it’s off to the lab with him. By stunning coincidence, Billy Peltzer happens to be employed at the very same building, as a corporate artist, while his love interest from the first movie, Kate (Cates), toils there, too, as a tour guide.

Gizmo is whisked away to be poked and prodded by the boffins, their boss an appropriately creepy Christopher Lee. But of course they disregard the tenets of mogwai ownership. No exposure to sunlight (fatal), no contact with water (it will spawn loads of other mogwais) and no feeding after midnight (the mogwais will transform into gremlins). Soon reptilian imps are swarming all over Clamp Tower.

“Clamp Tower”? Yes, Dante and his collaborators really were laying on the Trump comparisons.

“[Trump] was an emblem of what was going on in the Eighties and Nineties with greed and money and crassness,” screenwriter Haas told Wired. “And [the idea of] the whole world being for sale. But he still seemed sort of harmless.”

Clamp wasn’t 100 per cent a Trump clone, it’s important to note. Clamp Tower also hosts a satellite TV wing, a clear wink at CNN founder Ted Turner.

Yet it is the Donald-ness that shines through, with all the classiness of a novelty light-up tie. He’s always messing with his hair; his smile has the searing quality of a overloaded sun-bed. “You know, I’ve been thinking, Mr Clamp would make a great president,” someone observes in the DVD edition.

Trump has never acknowledged or commented upon the character but you suspect he probably wasn’t terribly insulted. Clamp, as written by Haas, was an oily bully. However, veteran stage actor John Glover brought warmth and vivacity to the part. Even when he’s being bad – such as when trying to buy out Mr Wing and demolish his premises – he’s hard to genuinely hate.

“He was so likeable and boyish and gee whiz, he started to become sympathetic,” Dante would say. He did, however, discern the Trumpian arc that stretched ahead for Clamp. “It’s hard to imagine politics wasn’t going to be in that character’s future”.

Watched today, Gremlins 2 feels like less like conventional entertainment than a bug-eyed commentary on Hollywood’s soul-stripping obsession with the bottom line. It starts with a sketch in which Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck – Dante really liked Looney Tunes – argue over the starring part in the cartoon curtain raiser. But they’re cut off prematurely and we’re hurtling forward into a bird’s-eye view of Manhattan.

The footage was originally shot for a Superman sequel (we’re supposed to be looking at Metropolis). Later, Dante squeezes in visual references to King Kong (a mogwai atop a model skyscraper) and an ET gag, with a gremlin cutting Billy off the line with an interdiction to “phone home”. Gizmo, for his part, dresses up as Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo (Stallone gave his blessing).

The gremlins themselves are even more out there than in the original. One morphs into “Spider Gremlin”, another turns into a bat, a third melds its DNA with a tomato.When “Bat Gremlin” flies through a wall, the imprint left behind is in the shape of a Batman symbol – a hat-tip towards the success, the previous year, of Tim Burton’s Batman. And in a big set piece, a gremlin dressed as Frank Sinatra sings “New York, New York”.

Even after the film’s release Dante continued with the in-jokes. For the VHS edition, the Hulk Hogan sketch is replaced with a scene in which the gremlins flick over to a John Wayne western. He whips out his pistol for a shootout with… three gremlins. In the David Bischoff novelisation, the evil genius “Brain Gremlin”, meanwhile, takes control of the book, locking the author in the bathroom. Behold, a property that breaks the fourth wall in three mediums.

The cinema takeover was initially rejected by executives at Warners. The worry was that people would indeed believe something had gone amiss and file out into the lobby. Spielberg, though, considered the conceit hilarious and intervened on behalf of Dante. He had a suggestion: why not try the gimmick at test screenings and gauge how punters responded?

“The gag where the film seems to break was particularly odious to the studio,” Dante recalled. “They told us, ‘If people think the film’s broken, they’ll leave’. And I had to point out to them that it would only take a couple of seconds, then [the audience] would figure out they’d been fooled, and they’d think it was funny.

He actually wanted to go further and sneak 2D gremlins into cinemas. “I thought it would be great if we shipped to the theatres some cardboard gremlin cut-outs with little springs on them. They could be attached to the projection booth windows, so that when people turned around to see what was wrong, they’d see these gremlins moving in the projection room. That didn’t fly.”

Critics loved Gremlins 2. The New York Times praised it for “speaking to the gleeful hell-raising monster in each of us”. And TheWashington Post hailed it as a “devilishly, hysterically, cacklingly, subversively funny picture that builds and builds until it literally self-destructs”.

Alas, filmgoers didn’t agree. With a budget five times that of the first Gremlins, it brought in just $40m at the box office. Punters wanted a sequel that played it straight – not one that mocked the fanbase for craving seconds.

Dante wasn’t too bothered. He’d fulfilled his contractual obligation and received a big pay-day. More importantly he’d delivered his point: not every film requires a sequel and when a studio is motivated only by lust for lucre the results will inevitably disappoint. It was as if he’d made Gremlins 2 as weird as possible in order to shut down any appetite for a Gremlins 3.

“When I was asked to do the sequel, which I originally turned down because it was so hard to make the first one… The only reason I decided to make the sequel was because years later they had tried to make a sequel and couldn’t figure out how to do it, and they really wanted another one,” he told Arrow in the Head in 2015.

“So they said to me, ‘If you give us a couple of cans of film with gremlins in them next summer, you can do whatever you want.’ And they gave me three times the money we had to make the first one. So I made Gremlins 2, which was essentially about how there didn’t need to be a sequel to Gremlins.”

.png?w=600)