When Manti Te’o burst onto the national football stage in 2009, no one could believe how incredibly wholesome he seemed to be: a Mormon Polynesian from Hawaii, a small-town hero with an All-American vibe who committed to play at one of the most storied – yet conservative – athletic programmes in the country at the University of Notre Dame.

Not only did Te’o excel on the field, but the tragic story that unfolded during his time at ND propelled him into college football legend status. He lost both his girlfriend and grandmother within 24 hours during his senior year, then went on to lead Notre Dame to such a victorious season that he became a contender for the Heisman Trophy. He finished second in voting at the New York City ceremony in 2012, where he spoke onstage about the loss of his girlfriend, Lennay.

Within weeks, the unbelievable lore that had built Te’o up came crashing down in an incredibly bizarre way – as so much of it was revealed to be just that: unbelievable.

Lennay, it turned out, had never existed.

Instead, she’d been the catfishing creation of another young Polynesian man, Ronaiah Tuiasosopo, who seemed tangentially associated with Te’o. Both catfisher and victim – barely out of their teens and both from close-knit Samoan communities – were thrust onto the world stage as questions swirled. Did they know each other? Was Te’o in on it? Was the football star gay? Had this been orchestrated to fuel his Heisman campaign?

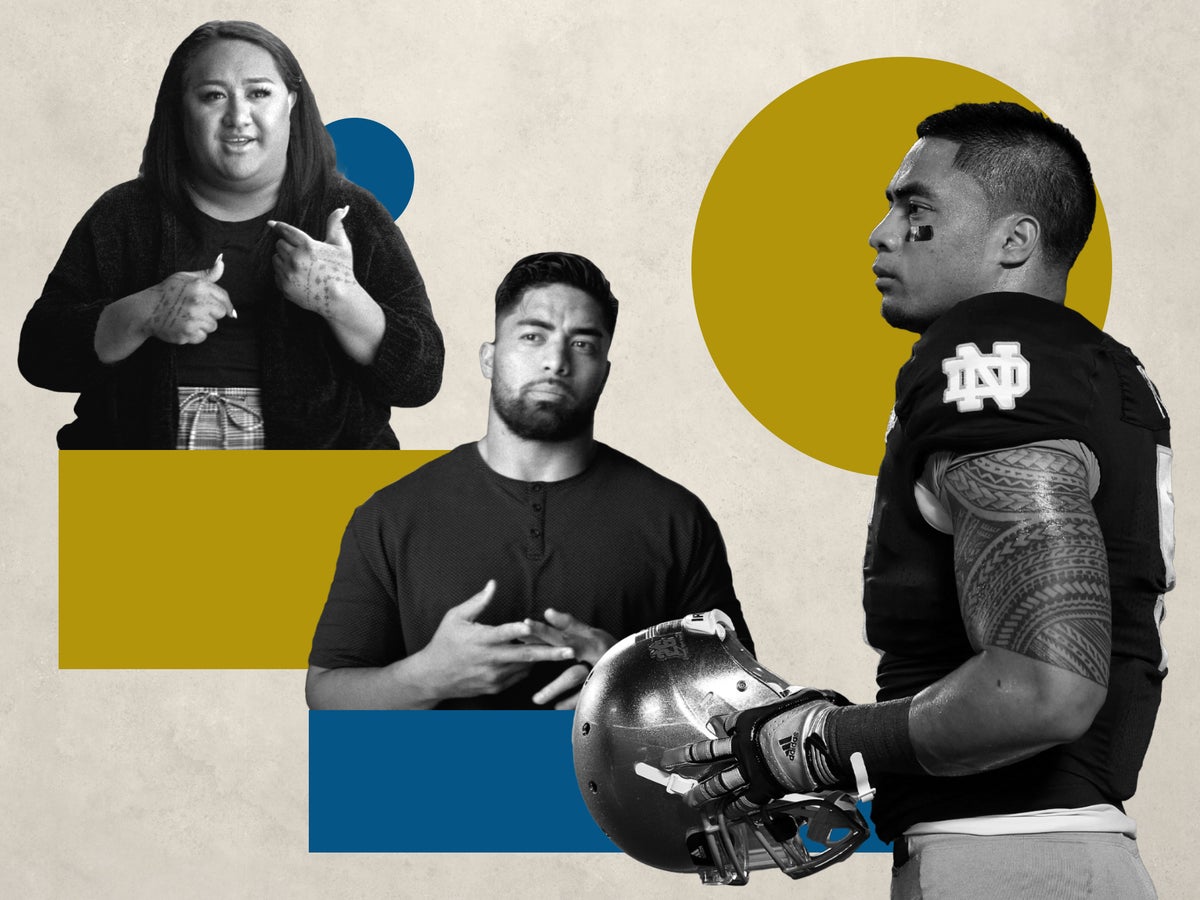

Ten years later, reflecting at length on the wild reality in a new documentary, both Te’o and Tuiasosopo still seem incredulous as they look back. The stories they tell are almost more eyebrow-raising than the initially hair-raising details that came out.

They’re also more heartbreaking.

Te’o is a married father now, his bearded jawline stronger, haircut sharper and manner both more confident and articulate. Tuiasosopo – who now goes by the shortened first name “Naya” – is living as a transgender woman and speaks thoughtfully onscreen about the events of 10 years ago, emphasizing points with perfectly manicured fingernails and nervous flicks of flowing dark hair.

“At the end of the day, the story is essentially ... a story of connections that ultimately ends in heartbreak and betrayal,” says Tony Vainuku, co-director of Untold: The Girlfriend Who Didn’t Exist, which debuts on Tuesday on Netflix.

“That’s simply what it is is,” he tells The Independent. “You’ve got to remember that they were young.”

Te’o was certainly young when he moved to Notre Dame as one of the hottest recruits for his 2009 freshman season. He was raised in the small coastal community of Laie on Oahu, where faith, family and football were the three major influences on his childhood.

The linebacker chose the South Bend powerhouse and, in 2009, headed from the beautiful shores of Hawaii to the freezing plains of Indiana, where he faced pretty serious culture shock and even called his dad crying, wanting to leave, according to the documentary.

When a beautiful Polynesian girl from California sent him a friend request, he accepted it, he says in the film – insisting he’d never heard of catfishing.

To put this in perspective, Facebook had only launched five years earlier.

“That wasn’t the culture back then,” Te’o says in the film. ‘In 2009 ... there’s no such thing. Nobody knew anything about catfishing.”

He says he checked with other members of the Polynesian community to verify some details about Lennay Kekua and was told people had interacted online with her.

None of them knew that the person behind the profile was not the long-haired woman pictured but instead a boy around Te’o’s age who’d also grown up playing football in the Polynesian community – but was struggling with his identity.

“Being a natural-born male, I could never be what I wanted,” Tuiasosopo says in the film, prompting the youth to choose “to have that experience in the life of a female even if it were fake. And so I created this whole fictional character.”

Tuiasosopo used a photo of a high school classmate to create the Lennay Kekua profile to interact with men and fulfill a fantasy the teen wished be played out in real life but felt was impossible, according to the documentary.

The profile was “something where I can act upon what makes me happy,” Tuiasosopo says.

“I knew what was right and wrong. But I was too far in love with being looked at in this way.”

Despite the fact that Te’o had never personally met Lennay, they began a relationship online and on the phone, with the catfisher employing such skilled voice manipulation that Tuiasosopo recreated Lennay’s voice on national television after the scandal broke to prove that no one else had been involved.

The relationship deepened, with Tuiasosopo inventing more and more ways to get attention. Sweet Lennay’s father wasn’t doing well and she needed to talk. Lennay’s little niece – in fact, Tuiasosopo’s real-life little sister – would get on the phone.

Think cryptic Facebook and AIM away messages that teens were wont to put up at the time – often for sympathy or to get a response from a specific crush.

That’s essentially what Tuiasosopo was doing – but taking it to a dishonest next-level. When Te’o wanted to FaceTime or meet up, Lennay shut it down.

“I’ve seen the show Catfish ... a couple times,” Tuiasosopo says in the film. “And a lot of their reasons for not being able to FaceTime, I would probably use all those reasons.”

Tuiasosopo did have an in-person meet with the football star while the catfisher was still living as a male and posing as Lennay’s cousin – and had spoken as a male on the phone with Te’o, too, still as Ronaiah.

The directors are still floored by the process of “finding out the details, of realizing how elaborate it was and how out-of-hand it got.”

Even before the scandal exploded internationally, Tuiasosopo – at least for a while – wanted out. In the past, Lennay would cut off communication or unfriend men on social media when things became too hard to keep up. And this had taken on a whole life of its own.

Tuiasosopo decided to “kill” Lennay; first she was in a car accident, then she had leukaemia, then she was dying. Posing as a relative, Tuiasosopo would call Te’o and hold up the phone to Lennay’s alleged hospital bed; Te’o says he could just hear breathing, like through an oxygen mask, as he spoke soothing words into the other end of the phone.

Right before Te’o’s major game against ND archrival Michigan State in 2012, Tuiasosopo, pretending to be Lennay’s brother, called Te’o sobbing to tell him she was dead.

“I felt like the worst person in the entire world. But I’m telling you, in that timeframe and where my mind was, I didn’t want to just end it with Manti,” Tuiasosopo says.

Te’o’s grandmother also died within the same 24-hour period – or around then, because the story would change in reports, helping lead to the eventual uncovering of the hoax.

When the ND star led the Fighting Irish to victory, Te’o’s inspirational quotes about his dead girlfriend and grandmother went viral.

“It was hard,” he said at a news conference after the game. “I lost a woman who I truly love, but I have my family around me and my football family. At the end of the day, families are forever and I will see them again someday ... I can honor them by the way I played.

“It was for them, for my girl and my grandma, and for all my loved ones who have passed on. They are all watching. It was a happy moment.

Tuiasosopo may have underestimated the impact Lennay’s “death” would have on the linebacker. Both of them say that twist in her story personally “broke” them.

“I don’t know what the heck inside me thought that he was going to handle it well, or like he was going to be able to just swallow that and just carry on with his normal, you know, routine,” Tuiasosopo says in the film. “But, um, yeah. He didn’t handle it well ... hearing him, like, literally slam things and scream and cry ... it broke me. It hurt me in ways that, I’ve never felt that type of pain.”

All of that was bad enough, but then Tuiasosopo inexplicably decided to resurrect Lennay – calling Te’o to say she’d been forced to temporarily disappear but was, in fact, alive. When he demanded proof, Tuiasosopo – using a ruse – got the high school acquaintance in Lennay’s profile photo to pose for a picture including the exact date and details he’d requested.

Te’o, confused and shocked, got this call not long before the Heisman ceremony in Times Square in December 2012, he says in the documentary. He still spoke about Lennay in the past tense on stage; looking at footage now from that evening, Te’o looks utterly shell-shocked.

“I had got a call two days earlier that the girl who I thought was dead is now alive, and I’m at the Heisman ceremony in New York,” Te’o says in the documentary. “And I’ve got a national championship game I got to play in.

“I don’t know what to think. I don’t know what to do – like, what’s true? What’s not true? And I can’t tell anybody what’s going on. I mean, what would you think? So I just stuck to the script.”

He told his horrified family about the incomprehensible situation – his dad, in the documentary, says his oldest son should have known better – and they called a relative who’s a lawyer. That’s the first time that Te’o heard the term cat-fishing, he says.

They eventually had to tell an equally dumbfounded Notre Dame, and all participants in the documentary insist Te’o was figuring out how to share the weird story with the rest of the world when all hell broke loose.

In January 2013, Deadspin published an expose.

The site – known primarily at the time for its columnists and snarky takes on sports news – received a message to its tip email address that happened to be picked up by an unpaid intern. Deadspin and its employees – along with the University of Notre Dame – form other major characters in the riveting documentary, which simply goes from one twist to the next.

Te’o and his father were caught unawares; Tuiasosopo ignored reporter calls for comment, he says in the film. He did, however, call the ND star.

“He just starts apologizing,” Teo’ says in the documentary, adding: “His exact words before anybody else found out: “I just wanted to apologize.” And I said, ‘What are you apologizing for?”’

He didn’t get an answer, and it was the last time the two would ever speak.

They were thrust together on a national stage, though, as everyone from Katie Couric to Dr Phil chased the story with astonished abandon. Tuiasosopo told Dr Phil he’d been in love with Te’o; Couric asked, in front of the linebacker’s parents, if he was gay. The jokes and the memes and the whispers didn’t seem to stop; Te’o played a quiet pro career, feeling haunted by the incident for a long time.

Tuiasaposo moved to American Samoa, began learning about the LGBTQ community and decided to start living as a woman.

“I used to think, ‘I’m never going to be able to show my face in public again,’” Tuiasoposo says in the documentary. “And then I was like, why wouldn’t I? Someone out there needs to hear my story, and someone out there needs to know that there is a light of hope.

“I still feel horrible, and sometimes I wish that everything had been undone – but then also another part of me was like, I learned so much about who I am today and who I want to become because of the lessons that I learned through the life of Lennay.”

Tuiasaposo was still transitioning during filming, the directors say, and the other participants – who did not meet her – were unaware.

Te’o, however, says in the film that he forgives Tuiasosopo – and tears up when describing how the entire saga affected his own life.

He says that his “challenge, every day, [is] that when somebody comes up to me and they say, ‘Manti, man, I’m a big fan of you,’ that I don’t think of the hundreds of people that said, ‘Manti, I’m a big fan of you, let me take a picture,’ and I took a picture with them, and they made fun of me.

“If there’s anything I’m going to do, what’s what I’m going to do – every day, you know, I’m gonna rise above all that ... no matter how hard it is for me.

“I’m gonna look at all these people who made fun of me and the people who actually believed in me,” he says, adding: “I have to take a second and be like, they actually love me. Man, they love you. They don’t want to make fun of you. Treat them nice in a world that’s just spit on you. Remember all those people in the stands that had leis on.”

Te’o says: “There’s gonna be one that’s gonna say, ‘You’re worth the world to me’ – and I play for that person. I’ll take this crap; I’ll take all the jokes. I’ll take the memes so I can be an inspiration for one that needs me to be.”

Two years ago this month, Te’o married health and fitness guru Jovi Nicole; they celebrated their daughter’s birthday last week. After playing with the San Diego Chargers and New Orleans Saints, Te’o became a free agent and has pursued entrepreneurial efforts over the years.

The participation of Te’o, Tuiasosopo and the other subjects prompted the directors’ jaws to “drop the whole time,” says Vainuku, who himself is Polynesian, expressing surprise at how “open” Te’o was, “ready as he was, vulnerable ... you can’t ask for a more prepared subject in documentary filmmaking.”

His co-director, Ryan Duffy, tells The Independent that both catfisher and catfished were “revisiting trauma.”

“And that doesn’t come cheap or easy – and it’s a credit to the both of them for being willing and vulnerable and honest to do it,” he says, adding: “They’re both in good places.

“And they were both able to look back on this and take this opportunity to really close the chapter and move on with their lives.”