Arriving in Ho Chi Minh City for the first time can feel like a shock to the system. Decades ago, you might have spotted bicycles wobbling through lantern-lit streets and buffaloes basking in opaque waters, but today, the modern metropolis is rather different.

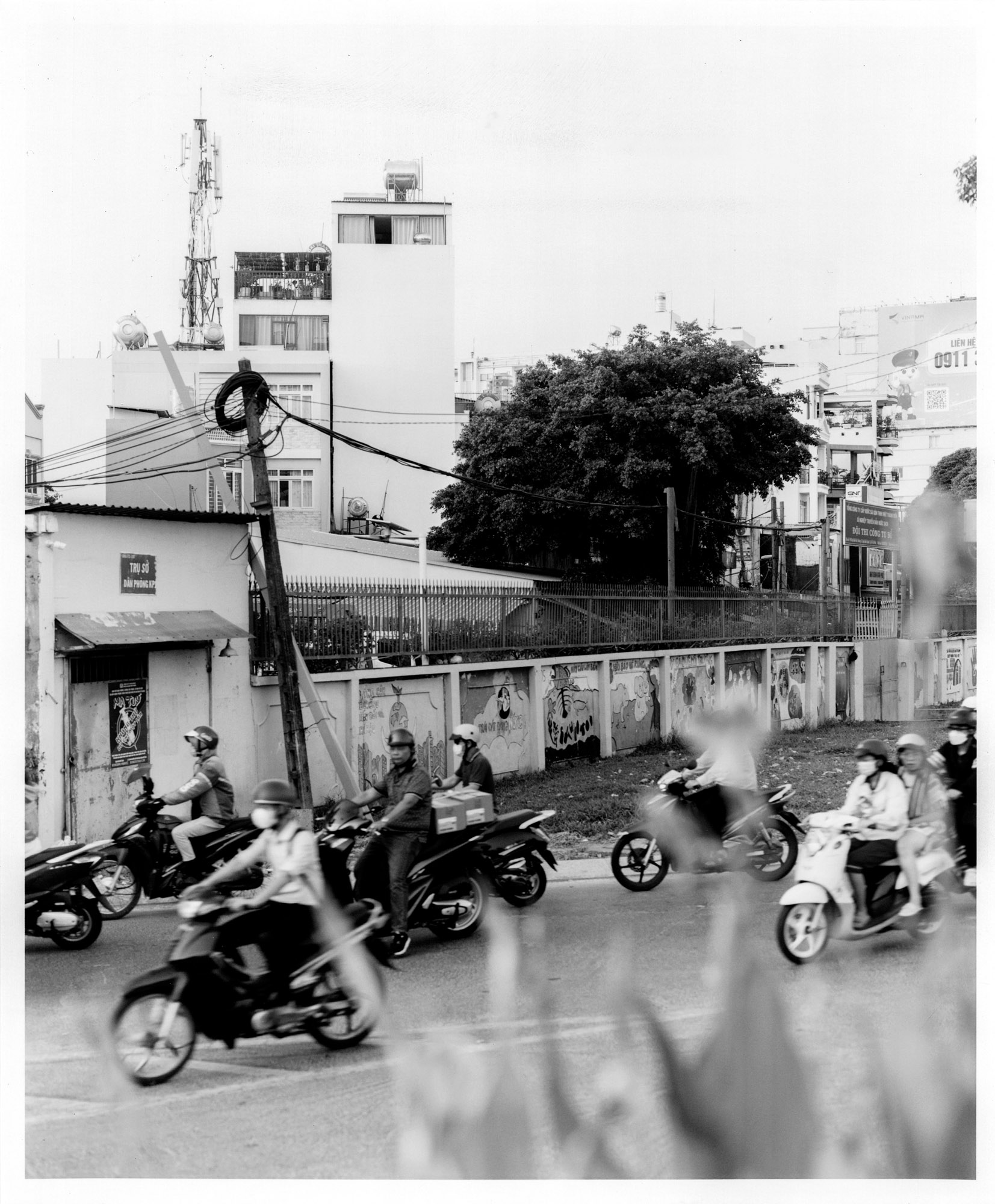

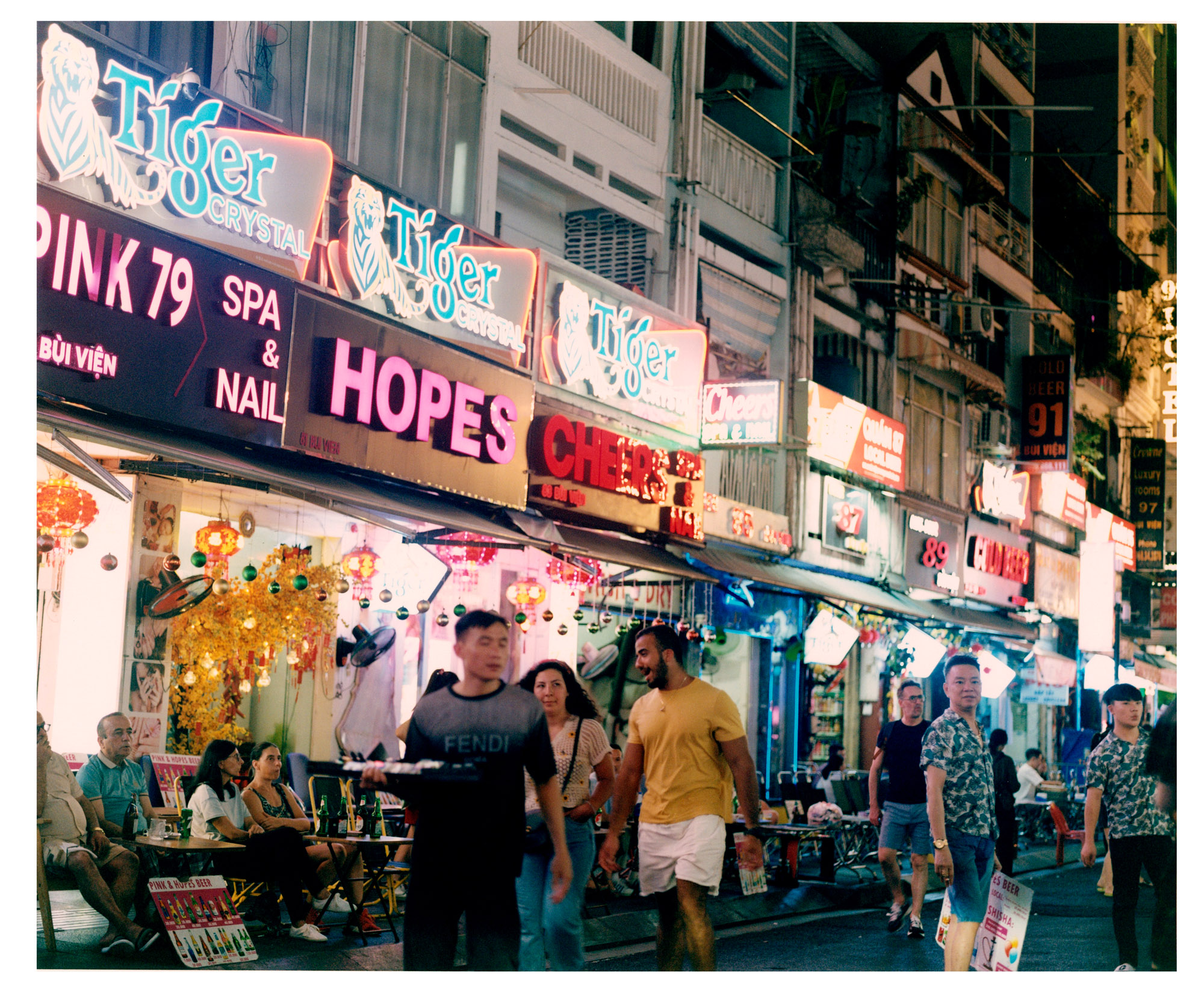

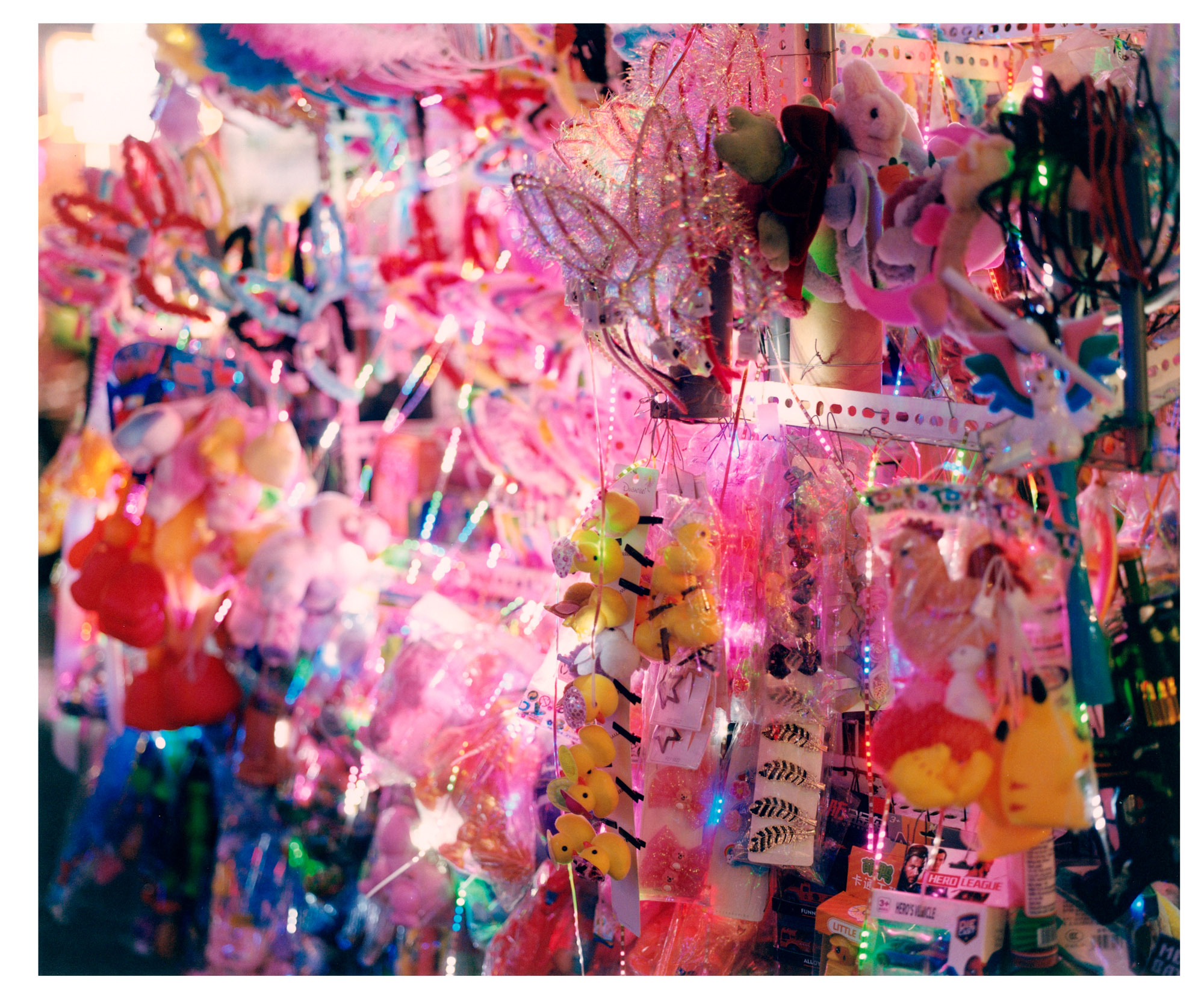

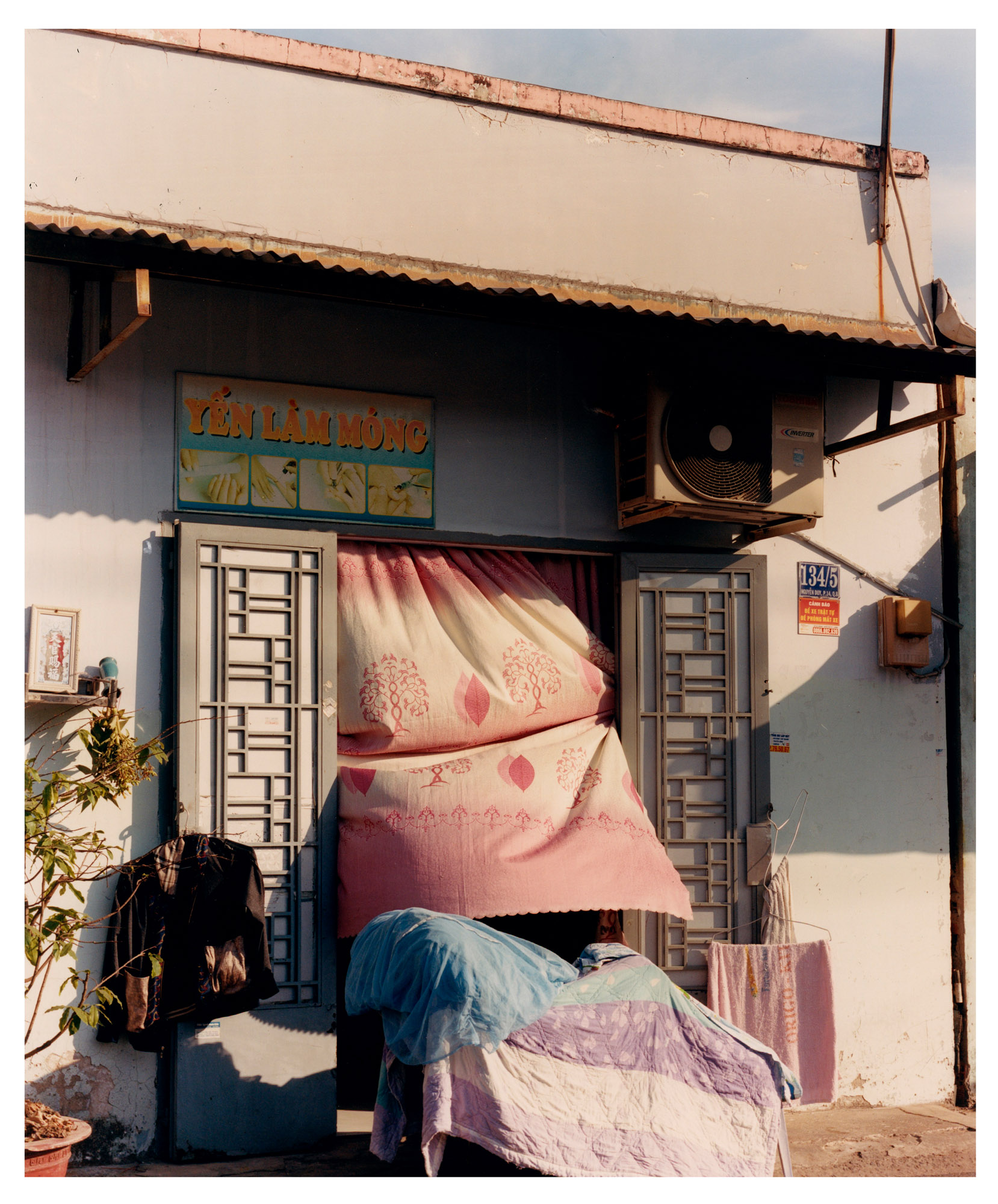

As your taxi crawls through the periphery of Ho Chi Minh City, besieged by motorbikes, you’ll encounter few cyclists and no fauna (save, perhaps, the odd pocket poodle). Instead, you’ll cruise through hyperactive streets flanked by terraced houses with ground-floor neon shops. Occasionally, a glass-clad office or hotel will interrupt the carnival of mismatched nha ong or ‘tube houses’. These skinny buildings, which can be less than 3m wide and up to 12 floors tall, have popped up all around Vietnam as a result of limited building space and property tax policies. The only design consistency seems to be deliberate inconsistency; after all, Ho Chi Minh City is a city that pushes you to stand out.

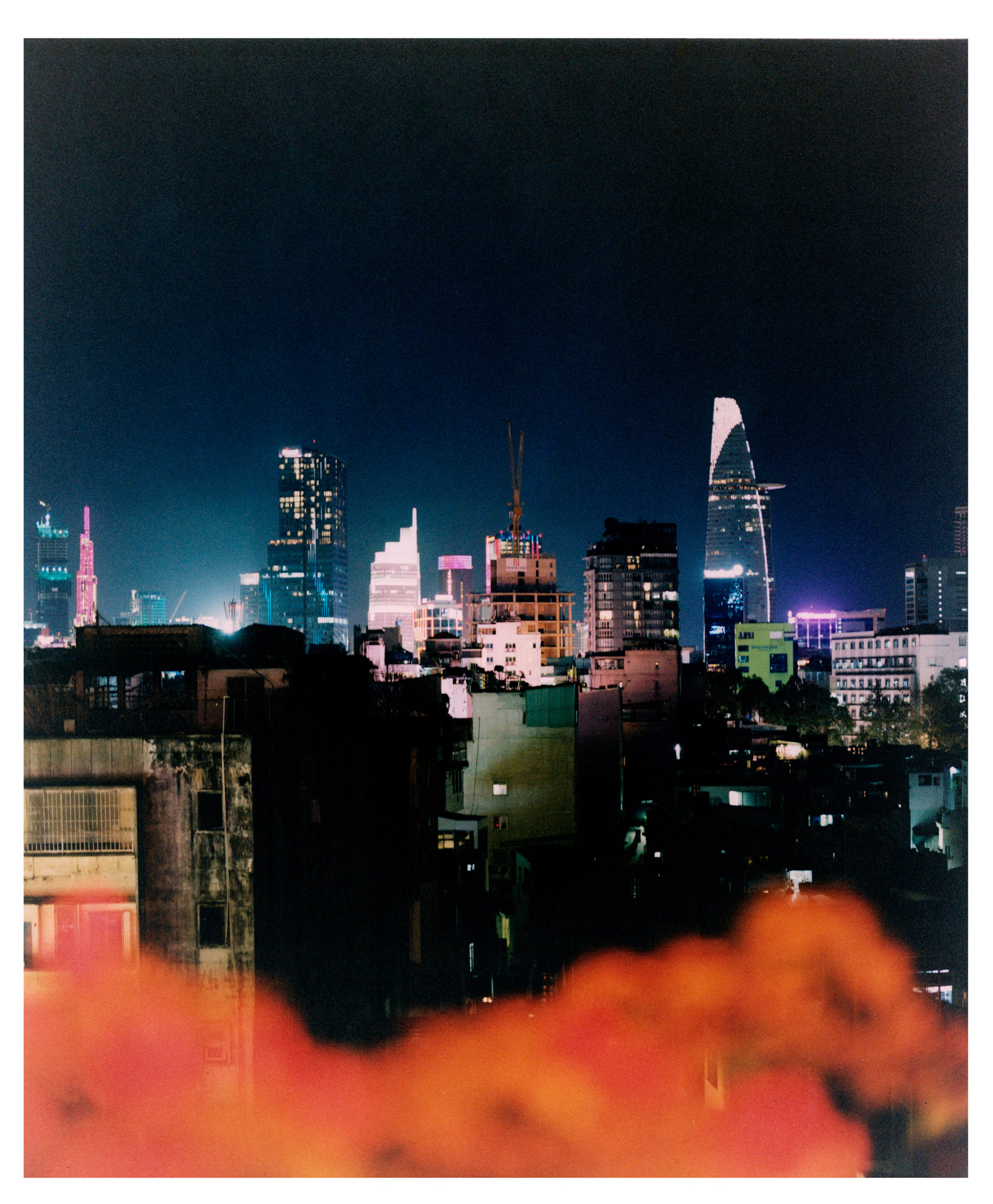

A rising star: Ho Chi Minh City

Within Ho Chi Minh City’s historic core, a sense of order emerges. In the early years of the colonial period (1862-1954), the French flattened much of the old city, founded around 400 years ago, and laid down a grid system that still gives structure to the city centre. Here you’ll find the city’s more storied architecture, such as the early 20th-century Jade Emperor Pagoda, a labyrinthine temple guarded by magenta walls, or Villa Le Voile, a flamboyant French mansion that is being turned into a cultural centre with help from restoration specialists Stonewest of London and Palazzo Spinelli of Florence.

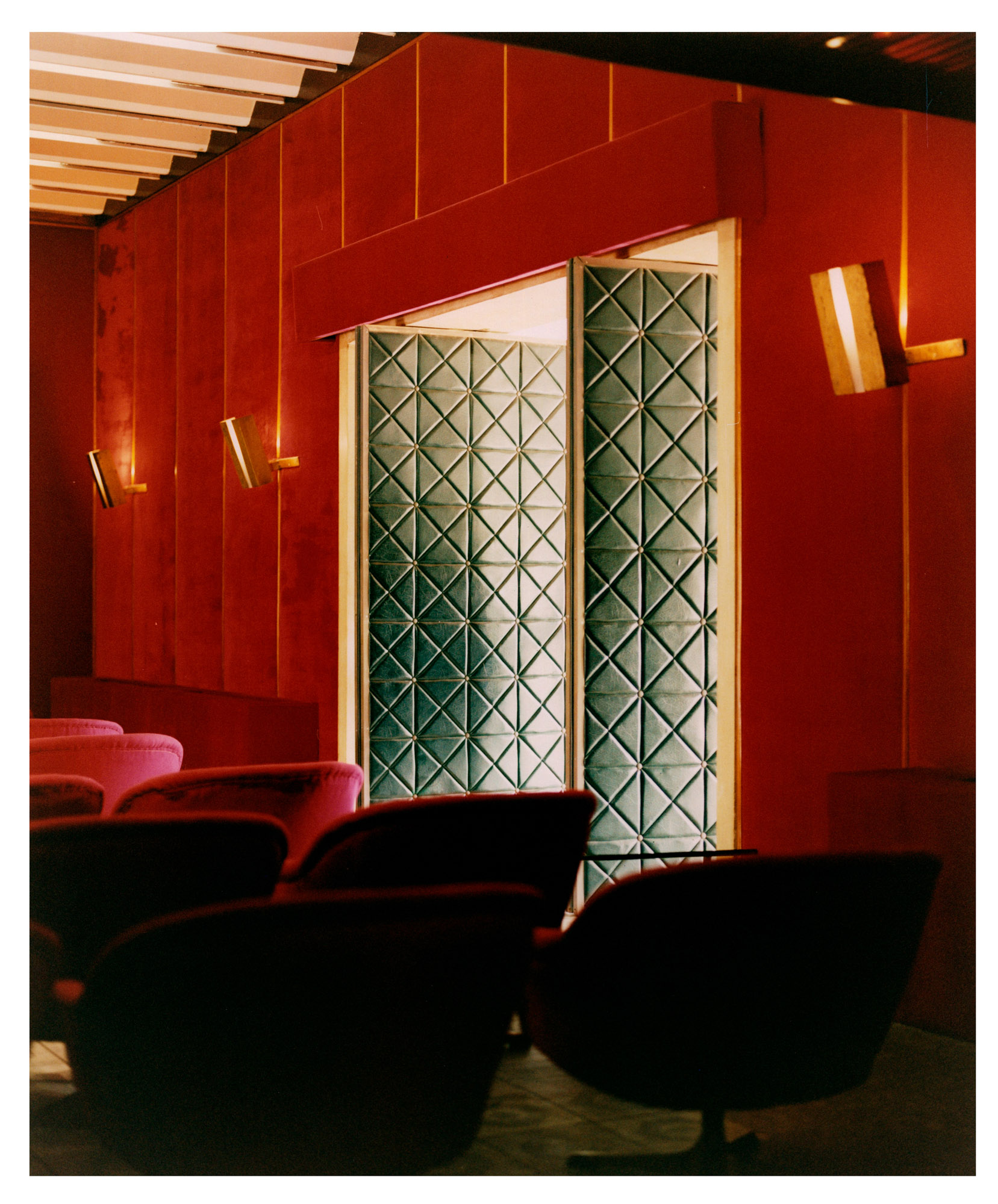

Nearby is local architect Ngo Viet Thu’s Independence Palace, completed in 1966 to replace a bombed French behemoth and now considered a paragon of Vietnam’s postcolonial modernism. The style, a branch of tropical modernism, borrowed minimalist design ideas from elsewhere in the world and adapted them to suit Vietnam’s heat and humidity. Less than a decade later, in 1975, North Vietnamese tanks rolled through the palace gates, bringing an end to the two decades of civil war that erupted after the French exit. A year later, the former capital of the defeated and defunct South Vietnam was bestowed a new name, Ho Chi Minh City, though the old name, Saigon, has proved difficult to shake.

The end of the war brought peace, but as history attests, this has always been a city of dissonance. Today, the tension lies in what kind of megacity the Saigonese want Ho Chi Minh City to be. Later to the development game than its regional peers, Vietnam is now one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies, and Ho Chi Minh City is its urban powerhouse. Can rapid progress prioritise liveability, respect heritage and foster creative communities?

‘Although [Saigon’s] rich and layered history often gets washed away in modern life, if you know where to look, you’ll uncover remarkable revelations’

Bill Nguyen, director of Nguyen Art Foundation (NAF)

‘Although [Saigon’s] rich and layered history often gets washed away in modern life, if you know where to look, you’ll uncover remarkable revelations,’ says Bill Nguyen, director of Nguyen Art Foundation (NAF), one of the city’s largest contemporary art collections. Born in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, Nguyen moved south in 2017. Ho Chi Minh City, a city of immigrants, ‘has always been Vietnam’s melting pot,’ he says. ‘What makes this place home to me is its embrace of diversity and acceptance. Here, you can be your authentic self without judgement.’

But in a city where you can be anything, almost anything goes. Urbanisation is wild and rampant, and this sets an example – and offers a warning – to Vietnam’s other cities, including the capital. Hanoian artist Nguyen Phuong Linh’s Rubber, Soap, Tobacco, a permanent installation at NAF, consists of three large cubes made of the titular commodities, in a commentary on a rapidly changing urban Vietnam. The smell of the installation saturates the small exhibition room, and as you move around the cubes, one scent transforms into the next.

Growing up in Hanoi, Phuong Linh would often cycle past old factories that produced these commodities. The living wartime remnants still belch the smells that inspired the artwork and are important reminders of the country’s industrial heritage, now under threat from developers keen to supplant them with apartment blocks. Made of organic matter, the ageing artwork will warp over time, though nobody can predict exactly how. ‘I can’t control how the work might degrade, but that’s part of it,’ says Phuong Linh. ‘We can’t know what might be ruined and what might remain.’

The Ho Chi Minh City of today is unrecognisable from the Saigon of half a century ago. This is most evident on the east side of the Saigon River, a new development area attracting big investments and bigger names. Foster + Partners are steering the evolution of The Global City, a 117-hectare masterplan with apartments, villas, schools, hospitals and shopping malls. Meanwhile, Büro Ole Scheeren is working on an ensemble of biophilic high-rise towers that overlook the river. The projects are ambitious, but Nguyen remains sceptical. ‘I can’t help but wonder, who are these projects for? Who can actually afford to live here?’

Nestled among the mega projects of the river’s east bank, homegrown biophilic talent is propagating more quietly; this is where Vo Trong Nghia of VTN Architects and Nguyen Hoang Manh of Mia Design Studio, two of Vietnam’s leading architects, advocate a greener vision for Ho Chi Minh City’s future. Ensconced in headquarters draped in foliage, they hope to nurture Vietnam’s next generation of community-orientated and sustainability-focused architects.

West of the centre, local firm Tropical Space completed the Premier Office in 2022 using bricks. ‘Our philosophy is about letting the natural world in,’ says co-founder Tran Thi Ngu Ngon, who was born in Dong Nai, a province north-east of Saigon. ‘Sunlight, the breeze, even the rain can help craft the indoor environment. We don’t want to fight against nature. We want to embrace it.’ The bioclimatic, seven-floor office building seeks to maximise natural light while minimising heat from the sun, with a tree-studded buffer layer and perforated walls. The hope, Thi Ngu Ngon says, is that tenderly connecting office workers with the outside world will spark creativity.

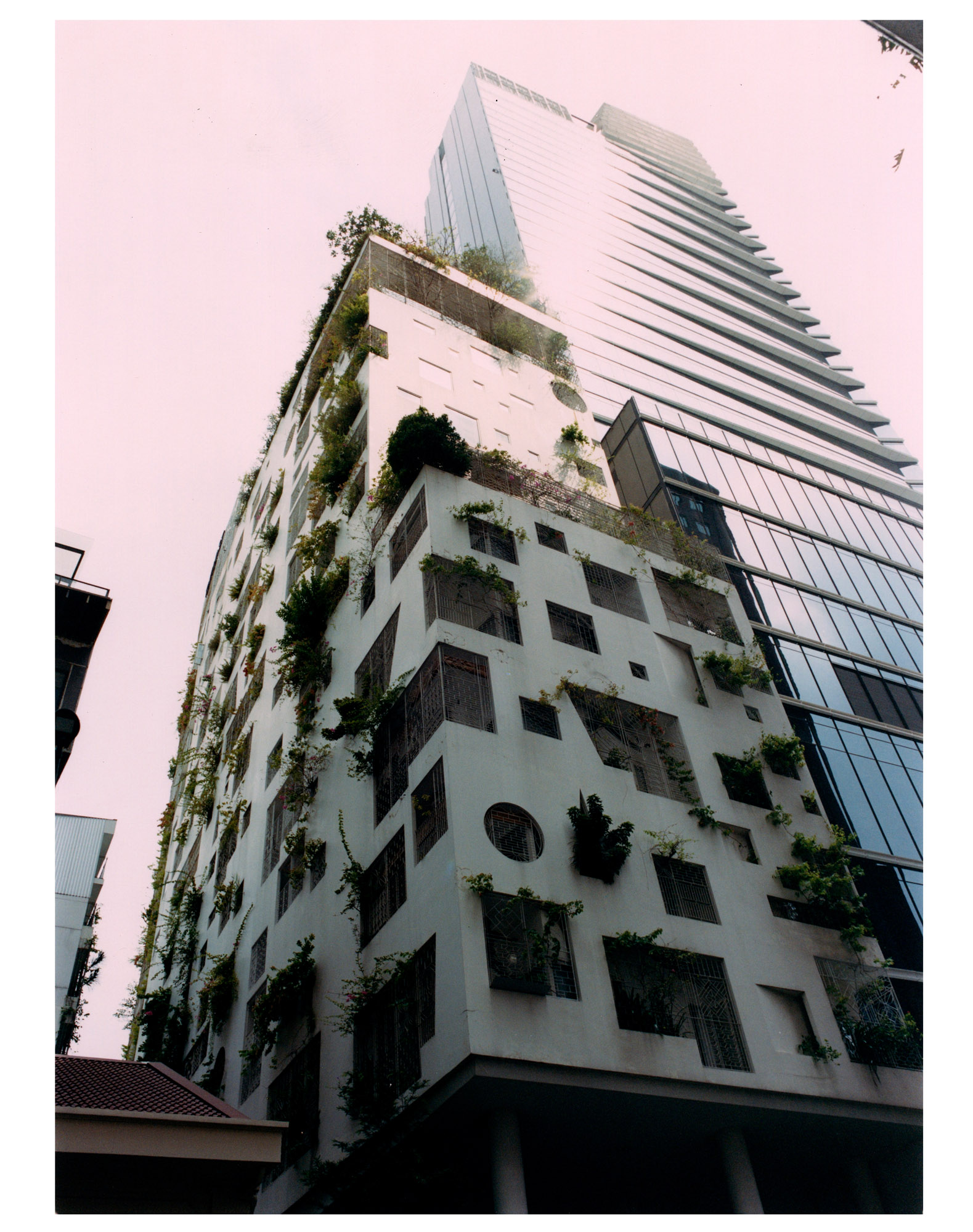

Inside the colonial grid and dwarfed by the recently renovated Park Hyatt Saigon, you’ll find A21studio’s The Myst Dong Khoi, a theatrical example of Vietnam’s biophilia. The 18-storey hotel’s prominent feature is a white façade with a patchwork of large square openings, through which foliage bursts forth. Step inside, however, and you’ll discover a subtle lamentation of the city’s disappeared heritage. A decade ago, developers destroyed the nearby 200-year-old Ba Son shipyard to make space for high-rise apartment buildings. A21studio used reclaimed materials from the wreckage – including a giant anchor – to embellish the hotel’s Bason Café, in a permanent exhibition that contemplates what was lost, and why.

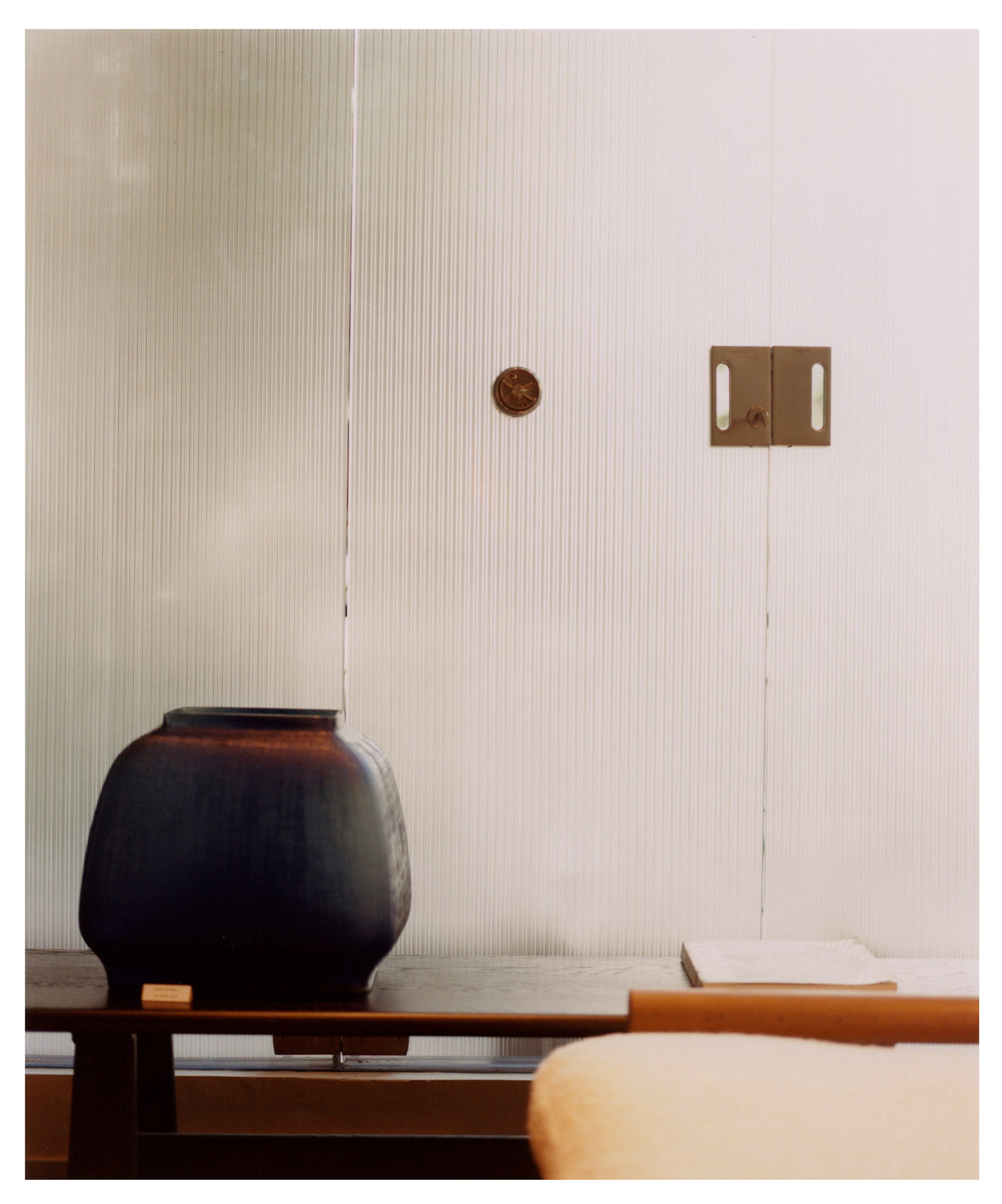

Repurposing heritage elsewhere in Ho Chi Minh City is less Frankensteinian, and probably most visible in the lively and seductive café culture. Speckling every district are affordable cafés that occupy upcycled buildings and spill out on to pavements. Lacaph seeks to refine Vietnamese coffee by offering high quality brews on the first floor of a colonial-era terraced shophouse. District Eight, a luxury furniture and homeware brand designing pieces informed by Vietnamese heritage, houses a cosy ground-floor café in its showroom with street-side seating. Architects SgnhA have injected modern touches into Okkio Duy Tan, a detached colonial mansion, and Sipply, a midcentury townhouse, to convert them into coffee shops.

Some cafés craft sweet treats that bridge Western and Vietnamese tastes. T3 Architects restored a modernist residence from the 1950s, rejuvenating lightwells, louvres and a garden that buffers the building from the road. Here you can pair your coffee with artisanal chocolate from The Cocoa Project. This chocolatier infuses its confections with provincial zest, like chewy sun-dried bananas from the Mekong Delta and spicy pepper from the northern mountains. A few blocks east, T3 Architects also designed Ivoire, a chic patisserie, with broad windows that bathe the lofty floors with natural light. Though, in essence, a European-style bakery, Ivoire incorporates tropical fruits such as guava, pineapple, persimmon and kumquat into its eye-catching desserts.

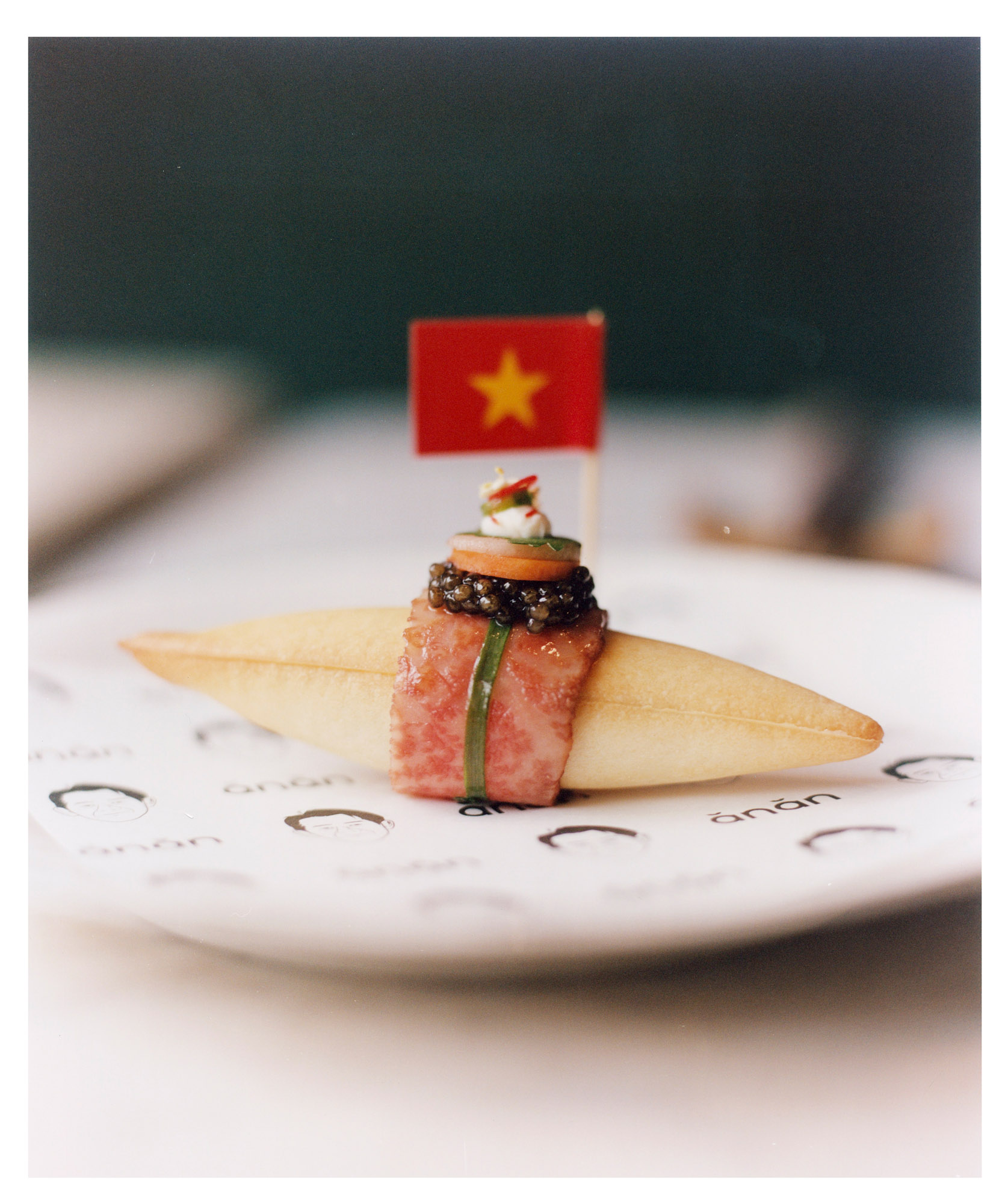

Contemporising classic flavours is a movement that’s in full swing. Vietnam has long been associated with cheap street eats, but challenging this outdated perception are a slew of fine dining restaurants born from traditional kitchens. At Anan Saigon which boasts the city’s only Michelin star, you can tuck into elevated versions of Vietnam’s best-known street food dishes, such as banh mi and pho. Over at Nén Light, the team has taken a more daring route by composing tasting menus featuring fresh dishes that remain grounded in traditional Vietnamese recipes.

‘When I arrived in Vietnam [in 2001], the culinary scene was mostly on the street,’ says Sarah Nguyen, the French creative director at StudioDuo, an architecture and interior design practice based in the city. Though she laments the bulldozing of street life to make way for a modern metropolis, she’s observed that ‘the change has brought positive things like new fusion restaurants that highlight more elaborate cuisine.’ At Yunka, a Nikkei restaurant, StudioDuo reimagined the first floor of a curved heritage corner building that combines art deco and modernist features. The firm extended the curvature to the interiors, with ‘natural patterns and free-form geometry,’ says Arturo Moreno, the Spanish architect at StudioDuo who moved to Saigon in 2015. This creates a fluid atmosphere boosted by a border of greenery.

The restaurant and nightclub may offer a glimpse of Ho Chi Minh City’s postmodern future: a hedonistic blend of surviving heritage, cosmopolitan clout and evolving narratives. ‘Next year marks the fall – or liberation depending on your point of view – of Saigon,’ says Bill Nguyen of NAF. ‘It will be intriguing to see what kind of narratives emerge from this event.

A version of this article appears in the June 2024 Travel Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today.