The history of Mexico has been written, all too often, with the blood of the victims of unspeakable tragedies. Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Aztecs and numerous other civilisations performed gruesome human sacrifice rituals. Today, bloodthirsty drug cartels terrorise local populations, sometimes with the cooperation of the authorities, as was revealed during last year’s massacre of 43 student protesters from an Ayotzinapa school. No one place embodies that painful history more than Tlatelolco.

Today a district of Mexico City, Tlatelolco began as a city-state on the shore of Lake Texcoco, eventually overtaken by the ascendant Aztecs, who made it a part of their empire. During the brutal conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés, in 1521 Tlatelolco was the site of the last battle between the Aztecs and the Spanish conquistadors. In the battle, Cortés triumphed, and some 40,000 Aztecs were killed. Centuries later, a plaque would be built on the site that reads: “The battle was not a triumph, nor was it a defeat. It was the painful birth of the mestizo nation that is the Mexico of today.”

The deaths of the battle left a scar on the national psyche of the new colony, and later Mexico. The Spaniards did their best to pave over Tlatelolco’s dark history, demolishing its temple and using the stones to build a church. Much later, in the 1950s, Mexican leaders resolved to finally right the wrongs suffered on the site, putting it to good use by building a modern housing project there.

Naturally, the new plans were the subject of more practical motives too. Mexico City had grown significantly since the Spanish conquest and was continuing to boom. After infrastructure projects drained Lake Texcoco, the city grew steadily out from the centre of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán, which today is Mexico City’s central plaza. After the country gained independence in 1810, gradual industrialisation during the 19th century and the creation of a railway network laid the foundations for a steady population shift from rural to urban. By the 1950s, Mexico City was facing a serious housing shortage.

Seeking to address this issue, the Mexican government sought to implement the most innovative building design of the time. They contracted Mario Pani, a young architect who had become one of the biggest proponents of the modernist ideas of Le Corbusier in the country.

His plan called for 102 residential towers, ranging in height from four to 22 floors, placed in large blocks with plazas and public space in between – Le Corbusier’s “towers in the park” concept. Additionally, the area near the recently excavated ruins of the former Tlatelolco temple and the Spanish church would be converted into a plaza, named Plaza de las Tres Culturas (“Square of the Three Cultures”, after the Aztecs, Spain and Mexico).

Though part of the plan’s rationale was to provide an economical solution to the housing crisis, it also claimed to improve the lives of the inhabitants of the complex, through the virtues of modern design. Pani believed that the complex would be part of a “general process of regeneration”. Far from achieving these lofty goals, the complex instead set the stage for the next instalment in Tlatelolco’s tragic history.

In 1968, Mexico City was preparing to host the Olympics. While the government saw the event as a way to raise Mexico’s stature in the eyes of the world, a coalition of left-leaning activists instead wanted to turn attention to social ills and the frequently violent overreach of military forces in Mexico. In response, the government created the Olympia battalion, a paramilitary squad intended to ensure the games wouldn’t be interrupted by protesters.

The protests reached tipping point on 2 October, 10 days before the opening ceremony, when protesters gathered in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the late afternoon for a rally. At the same time, snipers from the battalion took strategic posts in the new housing complexes, providing them with a clear shoton the people below.

At 6:10pm, a shot was fired, though no one was sure where it came from. Security forces acted immediately, opening fire on the protesters. “At that point,” journalist Elena Poniatowska wrote in her book The Night of Tlatelolco, “the Plaza de las Tres Culturas became a living hell.”

The protesters ran eastward, but many did not escape. The battalion and other security forces broke into residences, and the wide superblocks made fleeing protesters easy targets. After the killings ended, the government’s initial reaction was to minimise the carnage, estimating that only 24 had been killed. This figure was dramatically contradicted by other accounts. Poniatowska’s account includes an interview with a mother living in Tlatelolco who claims to have seen at least 65 dead bodies during the massacre. John Rodda, Olympic correspondent for The Guardian, witnessed the event and concluded 350 had been killed. Though the final body count remains unknown, photos surfaced in 2001 confirming key elements of Rodda’s testimony.

The tragic events that night left a lasting legacy and remain a hot topic in Mexican politics. Alongside the plaque to the 1521 defeat of the Aztecs, another was placed to the memory of the student demonstrators. But though the events were seen as an indictment of the Mexican government, they didn’t tarnish the reputation of the Tlatelolco complex itself. Two decades later, another tragedy would occur at the site that would do just that.

On the morning of 9 September 1985, Mexico was hit by an 8.1 magnitude earthquake. Though the epicentre was off the coast of the southwest state of Michoacán, it was powerful enough to cause major damage in Mexico City, demolishing buildings, damaging metro stations and killing thousands.

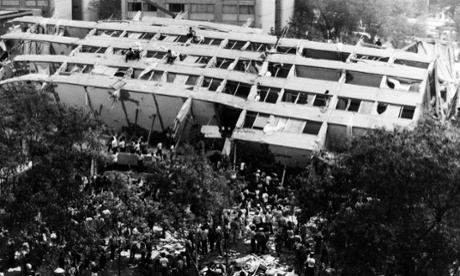

The Tlatelolco complex was hit particularly hard. Two of the three segments of the Nuevo León building collapsed, killing all residents inside. The collapse, exacerbated by a toxic combination of cost cutting during the original construction and improper maintenance, left between 200 and 300 dead.

Due to earthquake damage, eight other buildings in the complex were demolished and four more had their uppermost floors removed. It was an event charged with symbolism. Just as Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis, Missouri had demonstrated the “death of modernism” in the United States, the partial demolition of Tlatelolco showed it to be a failure south of the border as well.

Today, Tlatelolco seems to have put its tragic days in the past, but living conditions there remain far from perfect. Mexico’s El Universal characterises the complex as being under a virtual curfew at night, as high crime rates keep most people inside. In addition, the dangerous lack of maintenance persists. Architecture magazine Plataforma Arqitectonica reports that five of the buildings are inclined at a level of 1.5%, where buildings inclining greater than 1% are considered at risk.

But the downfall of modernism at Tlatelolco may also represent the rise of a new trend in housing, with a uniquely Latin American twist. This change is at the centre of the argument made by architecture critic Justin McGuirk in his recent book Radical Cities. McGuirk sees the decline of Tlatelolco as coinciding with the beginning of a new movement he calls “activist architecture”.

McGuirk highlights programmes such as slum upgrading and the social urbanism of Medellín, Colombia, to be the future of cities in Latin America, as well as the rest of the world. “[Activist architects] have to play off the private against the public to get the most out of both. They have to insinuate themselves into politicians’ plans,” he writes. “Above all, they have to be extroverts.”

The activist architect approach seems to be gaining ground among planning professionals, and it’s becoming increasingly popular in Mexico as well. Even in Tlatelolco itself, groups like Unidos por Tlatelolco (United for Tlatelolco) have emerged to coordinate the efforts of residents to make up for neglect by authorities whenever possible. Today, it seems clear that groups like these, just as much as central planning authorities, will be the ones to confront the difficult task of creating better living conditions for the citizens of Mexico.

- Which other buildings in the world tell stories about urban history? Share your own pictures and descriptions with GuardianWitness, on Twitter and Instagram using #hoc50 or let us know suggestions in the comments below