The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a product of a unique time in American filmmaking, when independent exploitation films were nastier than ever, and equally capable of piercing the mainstream consciousness.

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 film arrived in a recently transformed exhibition landscape. The 1967 outcry over onscreen violence in Bonnie and Clyde marked the end of Hollywood’s Motion Picture Production Code and the introduction of film ratings.

Films like Easy Rider (1969) elevated the standing of formerly disreputable exploitation fare within Hollywood. By 1973, The Exorcist was packing out cinemas and producing lines around city blocks with the promise of the most unremitting horror film yet made.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was shot quickly on a shoestring budget, financed in part by the newly-formed Texas Film Commission. The film assembled its cast and crew from Austin’s circles of recent college graduates and dropouts.

Its plot is straightforward enough: a group of young people are stranded when they run out of gas in rural Texas. They are terrorised and subsequently murdered by an eccentric local family, including the chainsaw wielding Leatherface – a nonverbal, childlike giant who wears masks made from the skin of his flayed victims.

We learn this family have lost their jobs at the local slaughterhouse with the introduction of bolt gun technologies, leaving them sell roadside meat made from human victims.

This detail has inspired a range of thematic interpretations for the film, encompassing commentary on class and family, gender and animal rights.

The film lays bare the horrors of meat production, inflicted on human victims. The family home is the site where these themes come into conflict.

Porn and violence on screen

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was picked up by the Bryanston Distributing Company. In 1972, Bryanston was the distributor for the theatrical release of the hardcore pornographic film Deep Throat. The film’s success shifted popular discourse around pornography, and helped Bryanston widen the theatrical release for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

In subsequent years, media reported on alleged abusive on-set conditions on Deep Throat, along with claims Bryanston was connected with organised crime. Director Hooper, and many of the Chain Saw Massacre cast, alleged they never received their share of box office from the distributor.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s proximity to Deep Throat stoked controversy, conflating concern about increasingly extreme depictions of sex and violence onscreen.

Two years earlier, young filmmaker Wes Craven had transitioned from making pornography to horror film. His low budget rape-revenge exploitation film The Last House on the Left (1972) was originally developed as a hardcore pornographic film. This approach was abandoned when it entered production.

Unlike Craven’s notorious film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is not overtly sexualised. While there may be a sexual undertone to Leatherface’s pursuit of Sally and her companions, it does not escalate to onscreen acts of sexual violence.

Regardless, the film drew condemnation, particularly in the United Kingdom, where it was banned, and later figured in public debates about the censorship of “video nasties” in the 1980s.

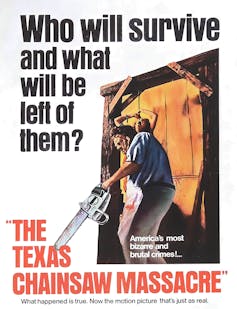

For my part, I remember encountering The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at the video rental store as a child: its title, cover and R-rating promised horrors beyond comprehension, many years before I actually saw the film itself.

Horrors implied, rather than shown

Beyond its controversies, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre played an important role in the developing field of horror film studies. It figures prominently in Robin Wood’s taxonomy of “reactionary” horror movies (which uphold traditional values) and “progressive” horror movies, which take a more ambivalent stance on the figure of the monster, challenging conservative social values. Wood counts The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in the latter category.

It is also central to Carol J. Clover’s influential codification of the “final girl” narrative trope, in which a sole young woman is able to withstand the monster’s onslaught.

Alongside Halloween (1978), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre helped steer the trajectory of American horror films in the 1980s.

Halloween is situated within the manicured surroundings of suburbia, and conveys its menace through the slick technical qualities of its gliding camera, and John Carpenter’s staccato synth score.

By contrast, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre locates its horror in the backroads and decrepit farmhouses of central Texas. The idea of Texas looms large, connoting a place of lawlessness, violence and danger.

Hooper punctuates his long shots with extreme close ups via rapid editing. The film’s most grotesque horrors are implied, rather than shown. Its most visceral impact comes from its extended chase sequences, and via its soundtrack: Sally’s piercing screams, and Leatherface’s ever-present chainsaw.

While the Texas Chain Saw Massacre spawned several sequels and influenced even more imitators over the years, from the Ramones to Wolf Creek (2005) and X (2022), it has rarely been matched in its intensity, and its harrowing, visceral impact.

Nicholas Godfrey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.