Addressing reporters on 17 August, the French National Anti-Terrorist Prosecutor’s Office said that it had received “significant documentation relating to possible crimes committed by Syrian regime forces… during the Tadamon massacre in Damascus in 2013”. The French foreign affairs ministry continued, “the alleged facts are likely to constitute the most serious international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity and war crimes,” crimes for which French justice has universal jurisdiction. Last month’s development prompts us to recommend that you read this article/interview on the edifying investigation that brought the Tadamon massacre and the identity of some of its perpetrators to light.

In early 2019, at an international academic conference in Paris, a Syrian political activist approached a scholar of mass violence affiliated with the NIOD Institute of War, Holocaust & Genocide Studies (University of Amsterdam). Could they meet privately? A few hours later, the professor had in his possession 27 unedited videos documenting mass atrocities committed by members of Syria’s security forces. The videos had been copied from a computer located in the Damascus headquarters of Syria’s Office of Military Intelligence by a young soldier assumed to be loyal to Assad.

Two academics’ quest for justice

Three years later, on April 27, 2022, The Guardian published shocking images of the execution of 41 civilians that had taken place on April 16, 2013, in a neighbourhood on the south side of Damascus. The British newspaper named the two researchers from the University of Amsterdam who had provided the images and further evidence identifying the perpetrators of the massacre: on the one hand, Uğur Ümit Üngör, the above-mentioned scholar, a German historian of Turkish origins, and on the other, Annsar Shahhoud, a PhD student born in Syria who was researching incidents of mass violence in her country during the current conflict.

The day after The Guardian released the images, New Lines, an US magazine specialising in the Middle East, published an article by the researchers in which the two described how they used covert tactics to communicate with the murderers themselves. The work took three years, during which time they spoke to almost nobody else about what they were doing, not even to members of their families.

The one video that has been released to the public so far tells only part of the story. According to the researchers, 288 civilians lost their lives during the Tadamon Massacre, including 7 women and 12 children. The remaining footage records many more scenes of murder, other forms of violence, and clandestine efforts to clean up the carnage to hide the evidence.

Once their research completed, Uğur and Annsar turned the 27 videos over to the appropriate government authorities in the Netherlands, France and other European countries. They do not know what further use will be made of them.

Given my personal research interests and concern that the French-reading public know about the Tadamon Massacre, I asked Annsar and Uğur for an interview to hear about how they conducted their research. I reached them through a Syrian activist who had been a political prisoner. My own work examines the ways people have been describing the Syrian conflict by analysing the lexicon and narrative forms used by different factions.

Annsar and Uğur responded immediately to my request for an interview. What follows is a summary of our conversation via Zoom in which they described, step by step, how they went about conducting their secret investigation.

The case against making the videos public immediately

In Today in Focus, Uğur explained that from the moment he received the videos in 2019 until The Guardian published some of the images in April 2022, he and Annsar told nobody about them, with the exception of the Dutch police in compliance with the country’s “fiduciary obligations”, which required them to inform the authorities about the videos while they temporarily made private use of them.

“Our goal was to find a way to speak to these ‘professionals,’ who specialised in committing acts of mass violence. They did not know we had video evidence of their crimes.” (Uğur Ümit Üngör)

Uğur explained they had two options: go public with the videos immediately, via the media, or incorporate them into an ongoing project on mass violence in Syria sponsored by their research institute.

Going public right away with the videos would have been a mistake, Uğur concluded. Had we done so, Syrian activists would have immediately identified and denounced the killers on social media, which would have made it very difficult to get more information about the massacre. Once the videos went viral, the culprits would have gone underground and the Syrian government would have denied the authenticity of the footage. Releasing the videos would have no doubt produced 5 sensational minutes of emotional overkill, without providing anything more substantial. What is more, Uğur added, “we couldn’t make the videos public until the young soldier who had risked his life copying them had left Syria, which he only succeeded in doing at the end of 2021”.

How a fake Facebook profile gained a pro-Assad network’s trust

When Uğur returned to Amsterdam with the videos, he contacted Annsar Shahhoud, who was doing her PhD thesis on the role Syrian doctors had been playing since 2011 in government-sponsored campaigns of torture and murder.

To gather information for her dissertation, she had created a Facebook page under the pseudonym “Anna Sh.”. Mixing fact with fiction, Anna Sh. identified herself as a Syrian researcher based in the Netherlands, who was an Alawite loyalist of Assad. She was doing research, she explained, on the “successes” of the Syrian army since the conflict began in 2011.

Under this alias, Annsar had already attracted a network of several dozen Facebook friends affiliated with the Syrian government, including soldiers in the regular army, military intelligence agents and members of Assad’s special militia (NDF).

The videos now opened new avenues of research. Together, Uğur and Annsar decided to focus on 3 out of 27, each 6 minutes long, during which soldiers took turns filming one another committing acts of violence. As they raise their rifles and take aim, they move slowly, almost lethargically, with bored expressions on their faces.

The facts and the investigation

The only video released to the public so far is not recommended for sensitive people:

Surrounded by other members of his unit and filmed in broad daylight, a soldier kills 41 people. The victims arrive in a minibus. As they are forced out of the vehicle, we see that they are blindfolded with their hands tied behind their backs. Someone orders them to run, one by one, to escape the gunfire of “a local sniper”. In a matter of seconds, each victim lunges forward and disappears into the ditch prepared for the corpses, hit by a bullet or two in the back. When night falls, the soldiers burn the bodies, a detail confirmed by the images published in The Guardian.

By examining the videos’ metadata, Uğur and Annsar were able to determine the date of the mass murders, as April 16, 2013, but neither the location, the killers’ identities, nor the office responsible for ordering the massacre. For a year, they believed that this horrific crime had taken place in Yelda, a suburb south of Damascus, until a few research assistants from Syria, who came from the southern part of Damascus, recognised a road from the Tadamon district of the city in a few isolated frames from the videos Uğur and Annsar had shared with them.

Identifying Tadamon’s assassin

In January 2021, after a year and a half of research, the two researchers got a big break: While combing through thousands of profiles linked to followers of Anna Sh.’s Facebook page, Annsar pinned down the profile of a man whose face she had seen in one of the videos. This was the very same person she had watched kill almost all of the victims in that particular six-minute sequence.

Annsar contacted the man immediately. For a while they quickly communicated back and forth, before he grew suspicious and pulled back. Six months later, he contacted her again and opened up, during which time Anna Sh. succeeded in recording two video conferences with him.

The man was a warrant officer from the Damascus headquarters of the Office of Military Intelligence. In their conversations, they did not talk about Tadamon, but he admitted he “could not even remember how many people he had killed; there had been so many”.

With this breakthrough, the investigation not only identified the alleged assassin, but connected him to Syria’s Office of Military Intelligence, Branch 227. And in doing so, Annsar and Uğur produced the first piece of documented visual evidence of a mass murder that indisputably implicated the security apparatus of the Syrian government in crimes against humanity.

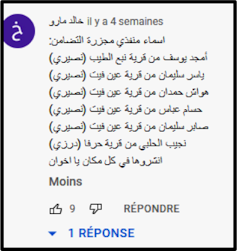

A few days after my conversation with Uğur and Annsar, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) announced that Amjad Youssef had been placed “under arrest” by his superiors in Branch 227. The network did not yet know what would become of him.

As for the victims themselves, they went from being described in general terms among the tens of thousands of civilians forcibly disappeared since 2013, to casualties of the “Tadamon Massacre,” murdered – and filmed – by members of Syria’s military intelligence.

The details of mass violence

As scholars of mass violence with special expertise in the Syrian case, Uğur and Annsar analyse the Tadamon Massacre through a theoretical lens that extends well beyond what they could see in the videos alone. But they also look at this specific case through what they call a ‘micro-space’, focusing on details that might elude those who only analyse mass violence at the macro, national level.

Uğur and Annsar show us that the Tadamon Massacre is only one “instantaneous sequence” of events, a single illustration of what Syria’s security forces have been doing since 2012 across the southern districts and suburbs of Damascus. Over time, they contend that the state policy went on to systematically exterminate and cleanse the region of people suspected, for one reason or another, as being in the opposition.

“In the Syrian case, it is important to distinguish between acts of mass violence, carried out by the secret police, which reflect the professional training of the killers, and acts of violence by amateur civilians, engaged in armed conflict.” (Uğur Ümit Üngör)

In order to effectively analyse how the Syrian government has resorted to violence to “cleanse” the nation, Uğur and Annsar use case studies. They divide the country up into “micro-spaces- by province, city, neighbourhood, or village – which yield more conclusive results”. Their goal is to establish, as completely as possible, the chain of command in each of the cases, all the way up the political hierarchy to the president of the country, with the aim of incriminating members of the security forces along the way.

Annsar Shahhoud clarifies what this means:

“Our studies of micro-spaces in Syria make it possible to distinguish between the primary goal of the regime – mass violence – and the specific tactics the government uses to escalate local disputes until all chaos breaks out. Our methodology allows us to follow the way the regime manipulates tensions within each community, in different spatial environments. In Homs, for example, in 2011, before the demonstrations had reached that city, the regime found ways to exacerbate feuds between Sunni and Alawite neighbourhoods, leading people to kidnap one another, creating an atmosphere of civil war. What you see in the Tadamon video is characteristic of the kinds of political tactics used by the regime in various other Syrian micro-spaces. The social nature of a particular space, its ethnic and religious composition and other sociological factors, determines which strategies the regime will adopt in one place or another as it lays the groundwork for achieving its final goal.”

In other words, in certain places such as Tadamon or the city of Homs, the regime would like us to see political factions lining up neatly along traditional ethnic and religious divisions (Alawites and Sunnis). And when that does not happen, seemingly on its own, with just a little encouragement from the outside, as it did not happen in Aleppo, then the regime immediately resorts to mass violence, against the entire civilian population, particularly when the area is controlled by anti-government forces.

Is the Syrian conflict a revolution, a civil war, or genocidal war?

Given Uğur and Annsar’s theoretical approach to the study of mass violence and their methodological innovations in the study of the Syrian case (micro-spatial methodology and Facebook interviews), their project makes an invaluable contribution to narratives about the Syrian conflict.

Thanks to their analysis, the confusing explanations routinely given for why civil war has broken out in Syria begin to evaporate.

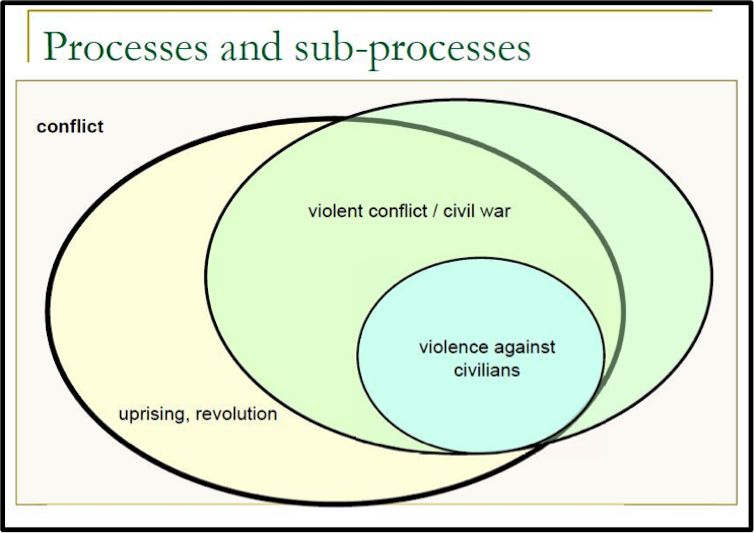

In an article on mass violence, Uğur stresses that in order to identify forms of violence in the context of a particular conflict, it helps to make a conceptual distinction between “the scale of fighting taking place among different military factions” and “the degree of mass violence committed against civilians.”

In Uğur’s opinion, the rapid outbreak of violence in Syria following the uprising in 2011, led to “a complex and lopsided civil war. Nevertheless, he added, the form and scale of the violence on the part of the Syrian regime can only be described as premeditated genocide directed in an indiscriminate way against the entire population in zones controlled by the rebels”.

In sum, Uğur claims that it is not exactly wrong to identify what is going on in Syria as a “civil war”. But in doing so, analysts obscure the well-documented fact that “from the very beginning of this revolution, the Syrian government has been organising and orchestrating mass violence”.

The video of the Tadamon Massacre further complicates the familiar narrative about the nature of Syria’s conflict. At first glance, for Syrians watching the video, the footage provides a simplistic and typical picture of a civil war: an Alawite soldier (recognised as such by his accent) methodically kills 41 civilians from a district in Damascus inhabited by Sunnis.

Uğur completed this observation:

“Yes, one of the murders in the video is Alawite, while the other one, who is filming, is Druze. But their boss is Sunni and the boss of their boss is Alawite. These ethnic/religious identities have nothing to do with the Syrian conflict. I firmly believe that the one and only relevant sect in Syria is Mukhabarat.”

Since Hafez Al-Assad built his security state empire, the term Mukhabarat [i.e. the military intelligence service of the Syrian government] resonates in Syrian society like the eye of Big Brother. Its secret agents are everywhere. They tap telephone lines; they infiltrate places of work and, depending on the part of the country, they find their way into people’s homes.

According to Uğur, those who belong to the Mukhabarat take on imaginary or supernatural personalities and assume unidentifiable nicknames, like “Abu Ali,” “Abu Stef,” “Abu Saqr,” etc. Annsar adds, having learned this from her interviews with members of the secret service:

“While talking to people working for Mukhabarat, you must never pronounce the word ‘Mukhabarat’ itself, because they are frightened by the very idea of the agency! It’s a never-ending circle of fear, paranoia, and terror.”

As for Amjad Youssef, the Syrian Network of Human Rights has confirmed that he never received a warrant or any other official document justifying his arrest.

Uğur had already made the same point:

“The regime is intelligent and keeps its criminals under tight control. It spies on them, keeps them together, or disposes of them as needed. Syria is a sealed box, a state of killers.”

This text was translated from French by Judith Friedlander, Professor Emerita of Anthropology at Hunter College (CUNY).

Mohamad Moustafa Alabsi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.