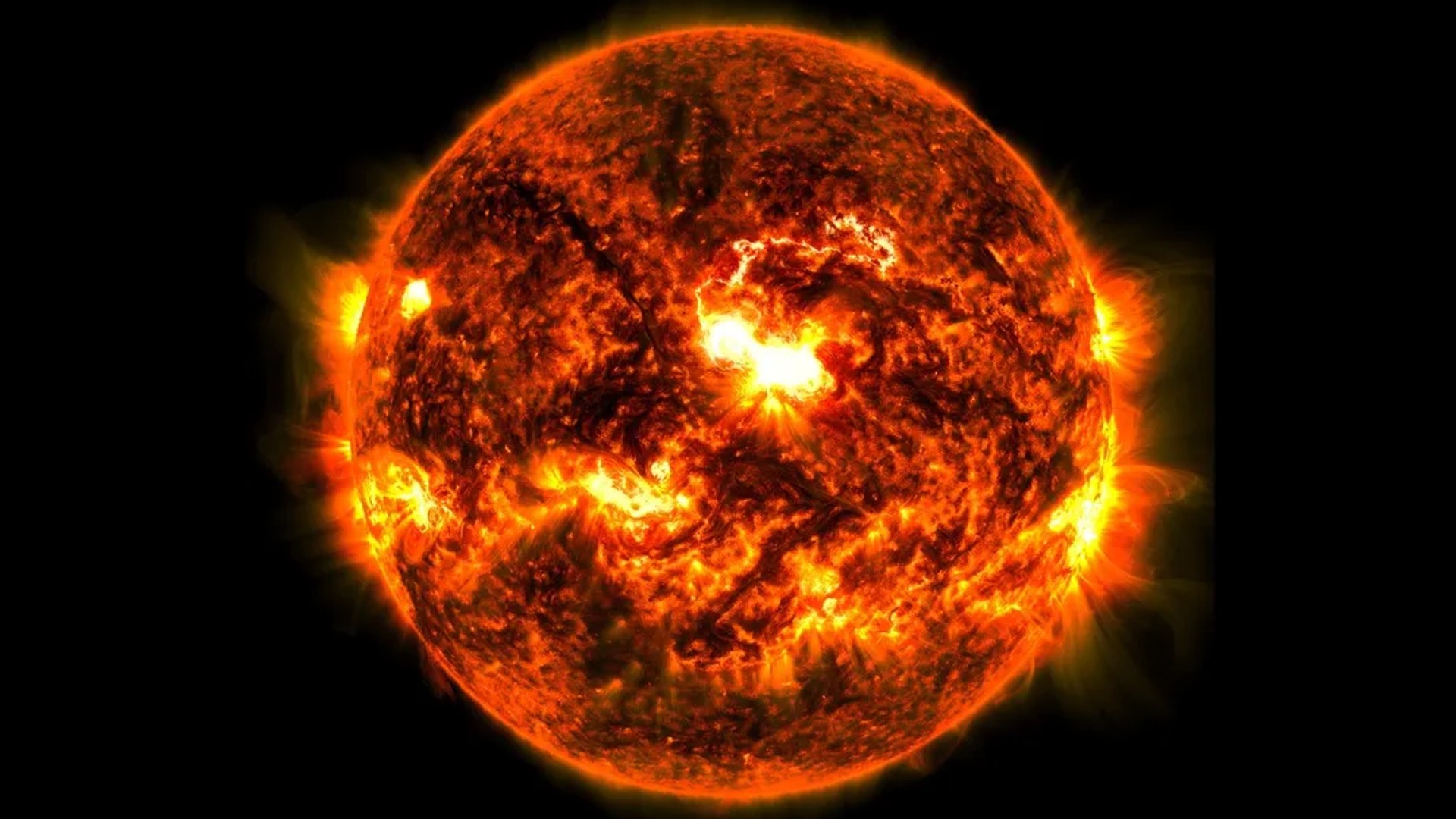

The sun may have swirling polar vortices similar to those on Earth, but powered by a very different source, according to a new study.

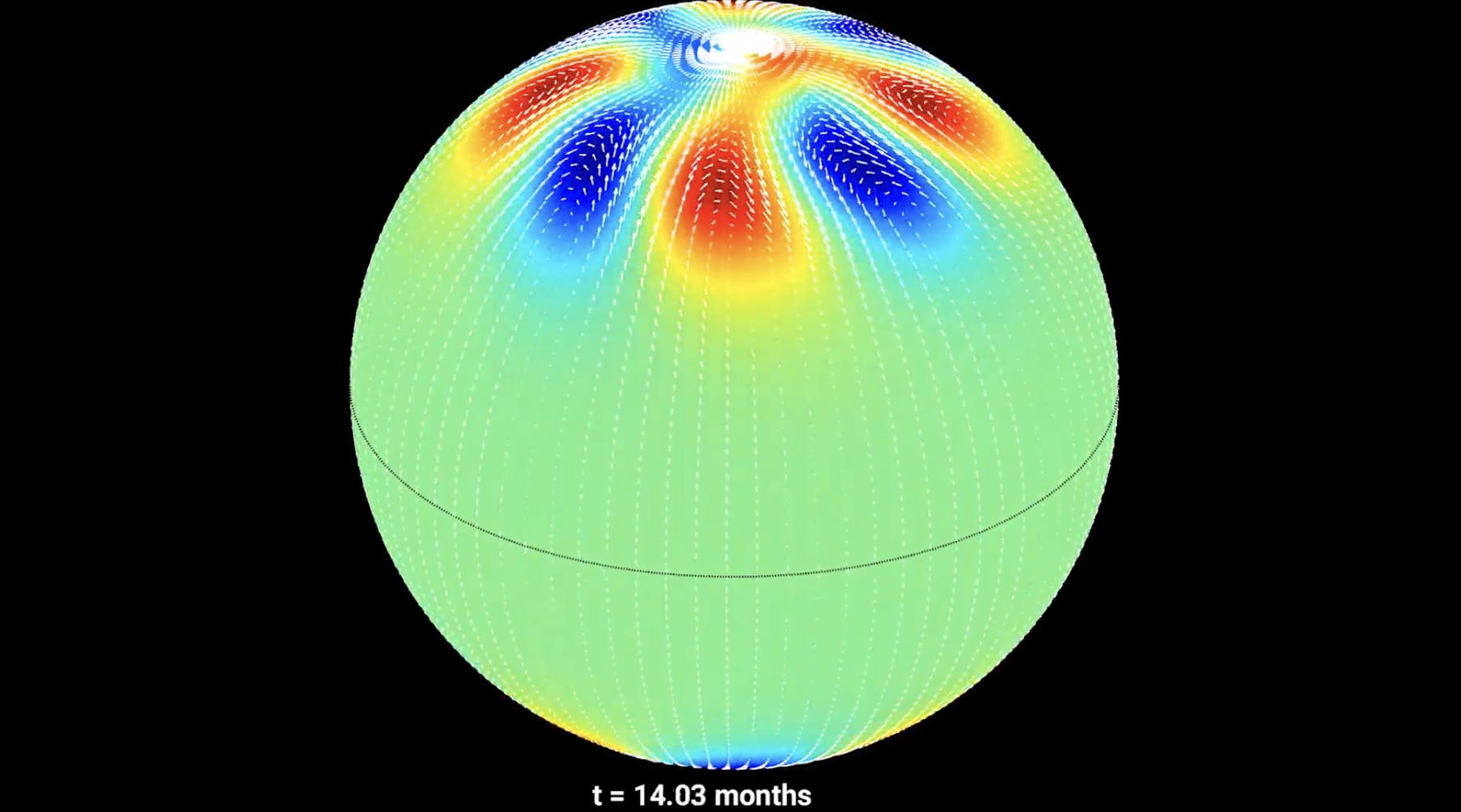

Current observations of the sun are limited to a face-on view, obscuring what can be seen transpiring at the poles — but researchers from the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR) simulated the sun's polar vortices using computer models, which suggest they're driven by powerful magnetic fields (whereas on Earth, with standard tornadoes, they are fueled by temperature differences in the planet's atmosphere).

"No one can say for certain what is happening at the solar poles," Mausumi Dikpati, lead author of the study and NSF NCAR senior scientist, said in a statement from the NCAR. "But this new research gives us an intriguing look at what we might expect to find when we are able, for the first time, to observe the solar poles."

Polar vortices have been observed on other planets, and even moons, in our solar system. These spinning forces develop in fluids that surround a rotating body due to what is known as the Coriolis effect. However, while planets and moons possess atmospheres, the sun's plasma "fluid" is magnetic. This is why you can think of these solar vortices as sorts of magnetic tornadoes on our star.

A phenomenon called "rush to the poles" may help explain the behavior of solar vortices. According to the team's computer models, polar vortices form at around 55 degrees latitude and move poleward. The magnetic field at the sun's poles and the ring of vortices have opposite polarity. Therefore, during solar maximum — the most active part of the sun's 11-year solar cycle — when the vortices reach the poles, a little flip-flop occurs, meaning the magnetic field at the sun's poles is replaced with a magnetic field of opposite polarity, according to the statement.

"These simulations offer a missing piece to the puzzle of how the sun's magnetic field behaves near the poles and may help answer some fundamental questions about the sun's solar cycles," researchers said in the statement. "For example, in the past many scientists have used the strength of the magnetic field that ‘rushes to the poles’ as a proxy for how strong the upcoming solar cycle is likely to be."

First-hand observations are needed to confirm the computer simulations of the solar vortices. However, to do so requires perfect timing, given the polar vortices can only be observed outside of a solar maximum, which is currently underway.

"You could launch a solar mission, and it could arrive to observe the poles at completely the wrong time," Scott McIntosh, co-author of the study, said in the statement, noting that a mission designed to observe the sun's poles from multiple, simultaneous viewpoints would offer valuable insight on the formation and evolution of solar vortices.

Their findings were published Nov. 11 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.