English Heritage is now selling what it calls “the best thing since sliced bread” at 13 of its sites – brown bread ice cream, inspired by a Georgian recipe. The announcement of the flavour mentions several more outlandish Georgian flavours trialled by English Heritage before it landed on brown bread, such as Parmesan and cucumber.

English Heritage is not alone in its efforts to beguile visitors with historical treats. In Edinburgh, the National Trust for Scotland’s Gladstone’s Land features an ice cream parlour linked to the dairy which stood there in 1904. The property sells elderflower and lemon curd ice cream based on a recipe from 1770, and visitors can go on several food-themed tours.

While brown bread ice cream, praised for its caramel nuttiness, may be a more familiar flavour to contemporary eaters than other historical offerings, the iced delights eaten in Britain in previous centuries took a huge variety of flavours and forms.

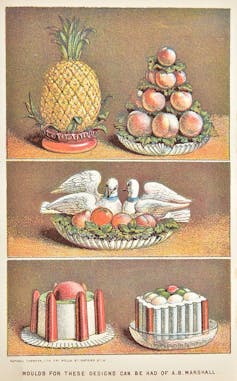

Agnes Marshall, the authority on ice cream during the late 19th century, published two cookbooks specifically about “ices” (1885) and “fancy ices” (1894). They included flavours from an elaborately moulded and coloured iced spinach à la crème, to little devilled ices in cups.

The latter consisted of a chicken pâté spiked with curry powder and Worcestershire sauce, egg yolks and anchovies, which was then mixed with gravy, gelatine and whipped cream, before being frozen in decorative cups and served “for a luncheon or second-course dish”.

Earlier texts contain even more outlandish flavours alongside the typical, sweet offerings.

French foodie Monsieur Emy’s L’Art de Bien Faire les Glaces d’Office (1768) has recipes for truffle, saffron and various cheese-flavoured ice creams.

The history of ice cream

By the time Marshall was publishing, ice cream was far more accessible to the public than in earlier centuries. Prior to the 1800s, ice was collected from frozen waterways and stored in underground ice houses, largely restricted to large estates with the necessary land, wealth and resources.

From the 1820s, however, ice was imported to Britain from Europe and then the US and stored in ice wells and warehouses. The importation of larger stocks of ice reduced costs, while simultaneously, innovators were designing apparatus for mechanical freezing.

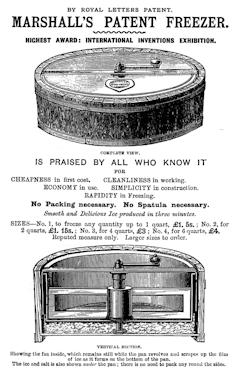

It would be a long time until ice was easily produced within the home, but cheaper ice made ice cream more readily available and implements were devised so it could be made at home. Both Emy and Marshall’s cookbooks depicting ice cream makers and Marshall’s patent freezer enlisted the same freezing technique as Emy’s Sarbotiere et son Seau (pot freezer and bucket).

Ice and salt were placed around a bucket, within which a custard or water mixture was stirred or rotated until it froze. Marshall’s innovation was the shallow pan, which gave an increased surface area for faster freezing. Equipped with such a freezer (and perhaps Marshall’s patent Ice Cave, for storing the ices), middle-class housewives could produce ice cream in their own kitchens.

Ice cream and leisure

Ice cream is well suited for engaging visitors at heritage properties today, not because of the history of how it was produced within the home but because of its holiday connotations. Whether it is a “99”, an “oyster” enjoyed at the beach, or the nearing jingle of an ice cream truck, ice cream has clear cultural and emotional links to recreation and enjoyment. This was also true in the past.

In 19th century Britain, street vendors (many of them Italian immigrants) began selling penny licks, or “hokey-pokey” from stalls or carts in the streets. In contrast to the immaculately-moulded delicacies in Marshall’s cookbook – which required the purchase of several pieces of equipment – this ice cream was to be enjoyed while out and about. It was also cheap, as implied by “penny” in the title.

Customers would purchase their ice upon a glass “lick”, eat it and then return the lick to the vendor for reuse. With growing numbers of seaside resorts and the rise of the leisure industry over the 19th century, ices were enjoyed while on holiday or daily excursions and at public events like exhibitions or fairs.

It is the portability of ice cream, as well as its culinary appeal, that has led to its lasting place in our leisure time – a delicious treat that can be enjoyed, one-handed, as part of a larger experience. The act of eating ice cream prepared from a Georgian or Victorian recipe therefore connects today’s visitors to a long tradition of enjoying ices recreationally.

While heritage properties are unlikely to embrace the more unsanitary ways ice cream used to be eaten, serving up historical recipes gives visitors a chance to savour a new sensory layer of the past. That taste can be linked into larger histories. From ice cream, we can learn about technological developments, changing attitudes towards sanitation, global travel, the availability of ingredients throughout time, trends, fashion and leisure habits.

Delving into the history of food – from the tins in our cupboards, to a cup of tea, or an ice cream at the beach – can bring new perspective to both the past and the present.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Lindsay Middleton's research was previously funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.