John Macris was shot dead as he got into his car on the street outside his home. Amad “Jay” Malkoun’s car blew up as he turned the ignition key. He survived but suffered severe injuries to his legs and arms. The two Australians apparently did not know each other. But they had an awful lot in common. They both liked flashy cars. Macris favoured Lamborghinis while Malkoun drove a white Mercedes AMG. They liked to work out in the same fitness centre in Athens called the Mega Gym, outside of which Malkoun’s car was mangled by the blast that nearly killed him on 1 March. They liked to dine in the same fish restaurant. They each had a glamorous wife – one was a reality TV star and model.

They were both convicted drug dealers and big names in Australia’s mobster firmament. Malkoun was the former leader of a criminal biker gang, the Comancheros. The other was a major figure in the Sydney underworld. Both had moved to Athens to start a new life. Both lived in the city’s plush seaside suburbs that guide books like to call the Athens Riviera, or sometimes the Hellenic Hamptons.

And both were the targets of attacks that left one of them dead – Macris perished in October – and the other in hiding in a private Athens clinic.

Was their joint presence in Athens pure chance? Or was there more to it? Greek police were baffled, as were the Australian media which for years had conscientiously covered the vagaries of their criminal careers. Macris, who was 46 when he died, had obvious links to Greece. He was of Greek-Australian stock, the family maintained strong links with their European homeland, and he spoke fluent Greek. But Malkoun’s arrival there two years ago is puzzling. Malkoun was of Christian Lebanese origin, and spoke little or no Greek.

Macris grew up in Sydney in a Greek-Australian family that was well-known to law enforcement. It was headed by Stelios Macris, who in 2014 managed to avoid a life prison sentence for possession of A$13m worth of methamphetamine oil, which is used to make crystal meth.

His other son, Alex, told a court that he had used his father as an unwitting drug mule and that Stelios had no idea that he was transporting drugs. Alex Macris also managed to walk free despite admitting that the huge drugs cache was his, as the court had granted him immunity from prosecution on the grounds that the evidence he gave was likely to incriminate himself.

Early in his career, John Macris went into partnership in a Sydney nightclub with another gangster, Todd O’Connor, who was murdered in 2008. He became a minor celebrity in Australia thanks to his relationship with a socialite named Roxy Jacenko, who ran a high-profile public relations firm called Sweaty Betty PR. But that came to an end in 2005 when he was jailed for two years for supplying a commercial quantity of drugs and handling suspected stolen goods.

He also regularly featured in the Australian media due to his long-running feud with the Ibrahims, another family that ran nightclubs in Sydney. Fadi Ibrahim was shot and almost killed in 2009. He and another brother, Michael, were later charged and stood trial for conspiring to murder John Macris in a mistaken revenge plot. They were acquitted.

Macris started travelling back and forth between Athens and Sydney about a decade ago and is believed to have settled in Greece about seven years ago. “I no longer have any underworld affiliation at all,” he told an Australian newspaper in 2009.

His new life in Europe was a glamorous one. He married his Greek-Ukrainian partner Viktoria Karida – a model and reality TV star in Greece – in 2016 on the island of Mykonos in a flashy ceremony that was lavishly covered by the Greek celebrity press.

He did appear, on the surface at least, to have settled into a bourgeois existence, walking his Pug dog in the hilltop streets around his minimalist four-storey villa in the Voula district of Athens, working out at the Mega Gym in nearby Glyfada, or dining regularly with his wife and their two small kids, Alexandra and Achilles, at a fish restaurant, the Barbounaki.

“They have a black pug called Richie. He’s friends with my pugs,” a neighbour, who declined to give his name, said the day after Macris’s murder. He, as did several other neighbours, said there was nothing about Macris that aroused suspicion, and that he seemed a happy family man.

“He was a cool guy,” said the neighbour, who said he would often chat with Macris when he bumped into him at the Mega Gym or at the Barbounaki restaurant. “He laughed a lot and he was always very kind. I knew he was working with a partner to set up a security company. They had invested a lot of money in buying cars and motorbikes. The plan was to provide security for celebrities and politicians and high society type of people.”

Macris was on his way to the launch party of that new security business – whose motto was “We believe in keeping you safe” – when he was murdered at 8.10pm on 31 October. His wife was modelling on an Athens catwalk and his father Stelios was at the family home when Macris left for the party. Instead of taking the Lamborghini parked inside his garage, he went out through the courtyard door, where a security guard was often positioned behind a one-way mirrored glass box that provided a view of the street, crossed the road and got into his Smart car.

CCTV footage leaked to Greek media shows a figure emerging from the darkness and firing through the car’s passenger seat window. Macris struggled out of the vehicle and managed to take a couple of steps, but was again shot by the assailant, who wore a baseball cap to cover his face. Macris died on the spot. He had been shot four times: in the stomach, chest and shoulder. The killer ran off into the darkness. Stelios Macris, the victim’s 82-year-old father, was the first to arrive at the scene and see the bullet-riddled body. “I saw my son die in front of me,” he would later say at John’s burial in Sydney.

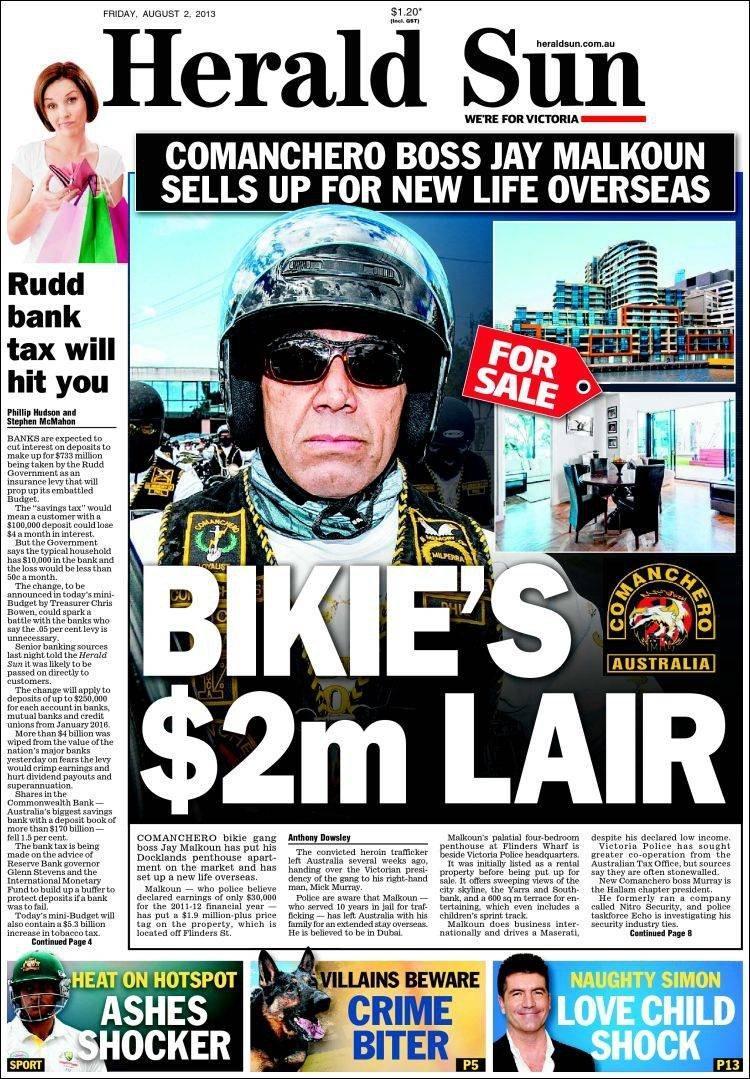

Amad Malkoun, 56, who preferred to use Jay as his first name, had been on the radar of law enforcement in Australia for most of his adult life. But it was in the late 1980s that he came to public attention, following his arrest for his part in a large drug syndicate, said Anthony Dowsley, a crime reporter at the Herald Sun, a Melbourne daily newspaper.

Malkoun, a champion kickboxer, was along with one of his brothers charged and jailed in Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison for his involvement in moving A$5.5m worth of heroin. “After his release from prison he was able to establish himself within Melbourne’s high society and its criminal underbelly. He was thought of as charismatic and persuasive,” said Dowsley, who has followed his career closely.

“Malkoun had also married a privately educated woman from Sydney and had the trappings of wealth by the time he became a key figure as ‘commander’ or ‘president’ of the most powerful outlaw bike gang in the nation, the Comancheros, in about 2010,” he said.

Before he left Australia in 2013 he was living in a penthouse in Melbourne’s central business district, overlooking the state police headquarters. “Basically, from Malkoun’s penthouse he could see the chief commissioner’s office,” said Dowsley.

His 2013 departure from his native land was a rushed one. He left as a covert police operation was under way into his activities. It was ultimately abandoned. Malkoun went to Thailand but left in 2015 after he was questioned by Thai police in relation to the abduction and murder – in Thailand – of former New South Wales Hells Angel member and drug trafficker Wayne Rodney Schneider. He then went to Dubai with his family and is thought to have moved to Greece in 2017.

There he lived, with his three young children, in a three-storey townhouse that overlooks the golf course in Glyfada and, beyond that, the waters of the Saronic Gulf dotted with ferries serving the Greek islands. His new life in Athens looked pretty much like that of Macris, whose home was just a few kilometres away from his. Neighbours said he was an attentive father, and would often wait with his kids for the school bus to arrive. He was seen in local shops buying ice cream for the children.

The Egyptian owner of the grocery store nearest to his home said that on one occasion he had remarked on the large tattoo of the Virgin Mary on his arm, and Malkoun, who is of Christian Lebanese origin, pointed to it and said “Al-Adhra”, the Arabic for the Virgin Mary. The shopkeeper then spoke to him in Arabic but quickly realised that Malkoun did not understand.

Neighbours said that the only routine he appeared to have was shepherding his kids to school and then heading for a morning workout at the Mega Gym. It was outside the gym that he was attacked on 1 March. He got into his white Mercedes AMG and turned the key. A bomb went off and he might have died had two passers-by not dragged him from the vehicle before the flames spread and engulfed it and the three cars next to it.

His wife Samantha Pyke – it is not clear if they are still a couple or separated – said she feared he was dead when she saw photos of the burnt-out remains of his car.

“You really cannot believe how he survived,” she told Australian media after she flew from her home in Perth to be with him and their children. He was treated in a public hospital and later at a private clinic – watched over by plain-clothes police and his own bodyguards – for serious wounds to the arms and legs.

Neither Malkoun nor Macris had a criminal record in Greece. Malkoun has insisted, like Macris, that he had come to Athens to live a quiet life and had given up his criminal pursuits. In a police interview leaked to Greek media, Malkoun said he had no idea who had tried to kill him and said he moved to Greece “because it is a very beautiful country”.

He and Macris did not appear to have known each other back home in Australia, and there was apparently no evidence that they had ever met in Athens, despite the fact that they frequented many of the same places. Neighbours of Macris who were shown photos of Malkoun said they had never seen him arriving at his house, and waiters at the Barbounaki restaurant, where both dined, said they had never seen them together. Mega Gym staff said the same.

But two major figures from Australia’s criminal underworld washing up on the same Greek shore seems to be more than a coincidence. And the attacks on the two men suggest their presence in Europe might not have been as innocent as they claimed. After Macris’s murder late last year, Greek police began examining various possibilities. One obvious line of inquiry was to ask if the hit had been ordered by one of his many enemies back home in Australia. Another was to find out if the killing was linked to a recent spate of violent turf wars in Athens that had left several dead. Just a day before his murder, a Greek underworld figure and security company owner was sprayed with bullets in an attack in the Athens port of Piraeus. He survived.

Was Macris taken out because he had tried to muscle in on the territory of established gangs in the drug trade or security business? There is a long list of organised crime groups in Greece that he might have offended: Greeks, Russians, Albanians, even Georgians. When they want someone dead, a standard tactic is to bring in a hitman from abroad, often from Albania, to do the job. Within hours of the grisly deed, the gunman is usually safely out of the country.

Weeks and months went by with no reported breakthrough in the police investigation into Macris’s murder and with no arrests made. Then on the morning of Friday 1 March reports came in of a car with Australian number plates being blown up in Glyfada. It quickly emerged that the owner of the car was an Australian named Malkoun. Australian media organisations quickly dispatched their Europe correspondents to Greece to report on the latest attack and to try and tease out any possible connection between it and the killing of John Macris.

Much mention was made of a dispute between Malkoun and Mick Murray, another Comanchero who took over the leadership of the biker gang’s franchise in the state of Victoria when Malkoun left Australia. Gang members, with allegiance to either man, have been battling it out in Australia. Or was Malkoun, like Macris, attacked because he was stepping on some local mobster’s toes? Malkoun’s alleged links to Russian organised crime figures were also part of the speculation.

But speculation was all it was, with police saying little. Until they announced, a month after the Malkoun bombing, that they had on 2 April arrested a Bulgarian man in a hotel in Glyfada and then charged him with the Macris murder.

“After a thorough and months-long investigation ... we managed to crack the case,” a triumphant Brigadier Georgios Kanellos told a press conference in Athens. “The perpetrators are two foreign-born brothers aged 31 and 33 years old.”

Police were still hunting for the arrested man’s brother, who they suspect acted as a lookout and drove the getaway car after the hit. The alleged killer had previously lived in Canada but had been deported for minor crimes in 2016.

The Greek newspaper Proto Thema reported that the brothers had arrived from the Bulgarian capital Sofia on 12 October, 19 days before the Macris murder, and had returned to Bulgaria hours after he was killed. Other media reports said police were investigating whether the arrested man had returned to Greece to carry out another contract hit, and whether he was the person who had planted the bomb in Malkoun’s Mercedes.

The arrested man, or his associates, have hired Alexandros Lykourezos, one of Greece’s best-known lawyers and one of its most expensive, to defend him. Lykourezos is best known for having defended Bosnian-Serb leader Ratko Mladic, who was convicted of crimes against humanity and genocide, at the International Court of Human Rights in The Hague. Lykourezos said his client in the Macris case was innocent and had simply been on holiday in Greece when the Australian was shot dead. His client had pointed out that the man in the CCTV footage of the murder was taller and thinner and was clearly not him.

The Bulgarian’s arrest was a major breakthrough in the investigation of the Macris murder. But it still left a lot of questions unanswered. Greek police said that that they believed Macris had been killed on the orders of an organised crime figure, but they were unable to say which one, or why. Nor did they say that they had established any link between his death and the near-deadly bomb attack on Malkoun.

Journalists dispatched to Athens quickly worked out the Mega Gym links between the two men, and the fact that they both liked to dine in the same Glyfada eatery. Another intriguing link also emerged. The house that Malkoun rented appeared to be owned by a wealthy Greek family which owns textile stores in Athens and in Russia. One of their stores was firebombed a year before Malkoun was targeted. The store was on the same short stretch of Vouliagmenis Avenue, a lengthy road leading into Athens city centre, where both the Mega Gym and Macris’s security company headquarters were located. Family members did not respond when contacted about their possible links to Malkoun, and that lead has for the moment dried up.

Greek media last week reported in April that police were looking into an alleged meeting between the pair a few weeks before Macris’s assassination last October. But there was no official confirmation of that, nor any detail about what the meeting, if it took place, was about. The Greek police may well know exactly what the two Australian gangsters were doing on their territory and are saying nothing for operational reasons. Or they may not have a clue.

Until they reveal what they know – and they may already have done so – or make more arrests, or until the Bulgarian in police custody talks, the mystery remains intact.

Was John Macris the head of an international drug-smuggling syndicate, using his Athens base to direct operations across the globe, as one Australian newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, claimed on 3 February this year? Or was he really trying to build a new and crime-free life as he claimed, and his past simply caught up with him? Was Jay Malkoun his partner in crime, or was he also trying to go straight?

To rephrase an aphorism by a famed Irish writer: one reformed Australian gangster’s past catching up with him may be regarded as a misfortune, but when it happens twice, this may be met with deep suspicion.