David Ballantyne wrote the Great New Zealand Novel in 1968 but is seldom recognised as a Māori author published long before Hone Tuwhare and Witi Ihimaera

In the world of Māori literature, ‘firsts’ matter. The foundational decades of modern Māori writing in English are defined largely by a sequence of milestone publications: No Ordinary Sun (1964) is the first poetry collection by Hone Tuwhare, while Pounamu, Pounamu (1972) and Tangi (1973) by Witi Ihimaera are the first short story collection and novel, respectively. These works – and their venerated authors – continue to demand respect, both as literature and as key cultural markers of a broader Māori renaissance.

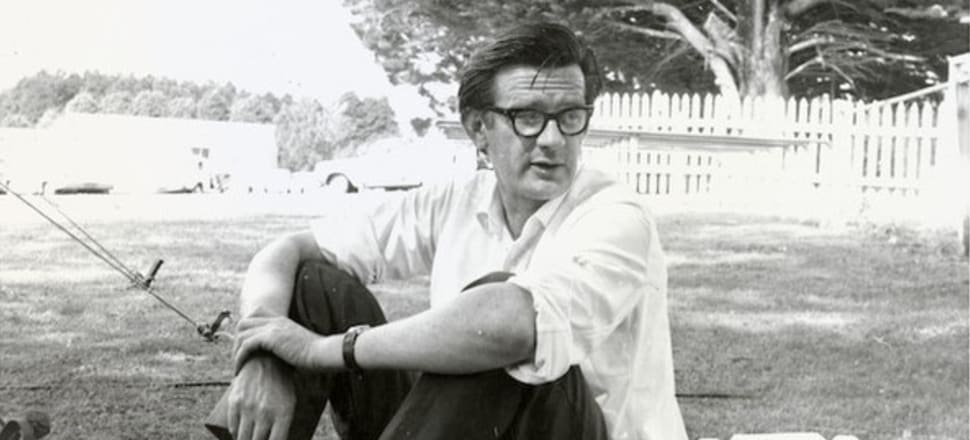

Yet these markers are complicated by the existence of David Ballantyne, a writer belonging to both Ngāti Uenukukōpako and Ngāti Hinepare of Te Arawa, who published four novels and a collection of short stories prior to the release of Ihimaera and his earliest works of fiction. Ballantyne’s reputation in Aotearoa has consistently failed to crystallise in the way that his talent arguably deserved; most accounts of his life and career are marked by disappointment and unfulfilled ambition – owing in part to the alcoholism that wracked his professional and personal lives. He died in 1986, aged 61, leaving behind some accomplished works, but no defined legacy.

In After the Fireworks: A Life of David Ballantyne (2004), biographer Bryan Reid hopes that the "residual sparks" of Ballantyne’s literary contributions "might yet re-ignite greater appreciation of a great talent", but he is also blunt about our current apathy: "‘David who?’ might have been the reaction of most New Zealand readers. Even the literary establishment appeared not to know quite what to do about Ballantyne, as C.K. Stead showed in his Landfall article of December 1979 when he drew attention to the meagre representation of Ballantyne in surveys and collections of New Zealand literature up to that time."

Ballantyne’s relative invisibility amongst readers and critics becomes even more puzzling when viewed through the lens of his Māori heritage. J C Sturm, for example, similarly struggled to find an audience (and publication) in her literary prime, yet her work is enjoying a resurgence, demonstrated in part by a new collection arriving next year. Collective interest in foundational works of modern Māori literature has never been higher – but Ballantyne, with his extensive bibliography of both published and unpublished work, remains largely unacknowledged as a Māori writer.

His being Māori is hardly a secret either. It is basically the first thing mentioned on his Te Ara page. He has an entry in the Kōmako database of Māori writers. Reid likewise devotes After the Fireworks’ opening pages to Ballantyne’s Māori heritage. His great-grandmother was Hēni Te Kiri Karamū (later known as Hēni Pore) who played a celebrated role at the battle of Gate Pā. Ballantyne was understood to be "quietly proud of his Māori heritage and especially of Hēni Pore", a point reinforced in a letter he wrote to Roderick Finlayson in which he drew on his background to appraise Finlayson’s collection of stories focused on Māori characters: "My grandmother ridicules anything that smells phoney, whether Māori or otherwise. She is, of course, proud of her Māori blood and so is my mother: ‘It’s the best part of you,’ I have been told for some time now. I like the stories, both for the technique and the skilful comedy and realism. My grandmother likes them because they are true."

However, it is clear from many sources – including Ballantyne’s own writing – that he was operating in an era where someone with Māori ‘ancestry’ was not necessarily considered ‘Māori’. Colonial ‘blood quantum’ measures have rightly been questioned and discredited in the decades since the publication of The Cunninghams – Ballantyne’s debut novel. If that novel was released today, readers and critics would, without issue, consider it a work of literature by a Māori writer. In 1948, however, Ballantyne was merely a Pākehā writer with some interesting facts in his family history – his ‘Māoriness’ was of the past, not something that could have positively shaped his present and future. Nor could it have informed a deeper understanding of his work.

This is the conception of Ballantyne that modern critics have inherited. There have been attempts to refresh and re-evaluate his legacy, but none – to the best of my knowledge – that attempt to engage with Ballantyne as a Māori writer. Hamish Clayton wrote an excellent reappraisal of Ballantyne’s subversive rural-gothic masterpiece Sydney Bridge Upside Down (published in 1968) in the Listener; however, his piece neglects Ballantyne’s Māori side entirely. The same is true of the novel’s new foreword, penned by Kate De Goldi (who, Clayton notes, was instrumental in getting Sydney Bridge Upside Down reprinted for a modern audience). It is unfathomable that modern critics – in attempting to ‘sell’ his writing to a modern audience – have consistently failed to mention one of the most striking aspects of David Ballantyne: that a Māori writer was writing and publishing novels with the scope of Sydney Bridge Upside Down years before (or decades before, in the case of The Cunninghams) the ‘first’ Māori novel was published in 1973, in the form of Tangi, by Witi Ihimaera.

While one might argue that Ballantyne being Māori is irrelevant to Sydney Bridge Upside Down – a novel that features no explicit references to Māori culture – the same can not be said for The Cunninghams, Ballantyne’s 1948 debut, and a classic novel in its own right. Described by Eric McCormick as "a masterly study of working-class family life in a New Zealand town", The Cunninghams is a hard, American-influenced piece of social realism that draws heavily on Ballantyne’s early life. Reid argues that with Ballantyne "the writing reflects the life", and that "The Cunninghams is the strongest demonstration of this close correspondence": "It tells the story of the Cunningham family at the end of the Great Depression and before the beginning of the Second World War; a family of five children, a father dying of tuberculosis and a mother desperately struggling to keep her children fed and clothed, utterly dependent on her husband’s pension as an invalid returned soldier. The narrative unfolds through the eyes of the eldest son, 11-year-old Gilbert, clever, a dreamer and a loner, suspended between childhood and adolescence […] As he feels his father slipping away from him, he finds himself moving closer to his mother, but at the same time becoming aware of her as a separate personality with her own desires, frustrations and dreams …"

Reid’s summary fails to address the fact that, in a reflection of Ballantyne’s own family, Helen Cunningham is Māori – a detail that adds an invaluable dimension to her creeping discontent with life in the small, suffocating town of Gladston. The Cunninghams introduces this dynamic through the minor character of Marjorie: the household’s young pregnant boarder who is in a relationship with Joe, a young Māori man from "up the coast". Joe is initially presented as absent and irresponsible – seemingly leaving Marjorie to fend for herself – and this problem is the window through which Ballantyne reveals Helen’s views on Māori: "I got nothing against the Maoris, Fred, and I always say my Maori blood is the best blood in me, but there’s a difference in the way they look at things. Especially these coast Maoris. They’re very casual, and of course Marjorie’s white, and the older Maoris are funny that way, they sort of look down on girls like Marjorie marrying the young Maoris. Mum’s mother was a half-caste, you know, Fred, so there’s quite a bit of Maori blood in me."

This chapter four speech – in addition to exemplifying Ballantyne’s touch for rambling, naturalistic dialogue – clearly reflects the pride that Ballantyne himself recalls from his mother about their Māori heritage. However, Helen’s blunt judgment also demonstrates a problematic element of the novel. Despite the protagonists being Māori, "the Maoris" are still othered throughout the novel, depicted as cultural outsiders in Gladston. In a later scene, a paranoid, broken Helen imagines the possibility of her husband, Gil, sleeping with "Maori tarts". Likewise, ‘the coast’ is regularly invoked as a foreign – almost otherworldly – place.

And yet there’s an unexpected warmth to Ballantyne’s depiction of Māori, which creates an interesting – if minor – narrative thread throughout the novel. Joe eventually does return, and his relationship with Marjorie resolves happily. In one scene, Helen meets Joe and Marjorie at a café for afternoon tea. Helen silently worries whether Joe will be able to afford the meal, but her unfounded assumption is upended when he is able to cover the table’s bill. Another memorable moment sees the young Gilbert – in the throes of his own sexual awakening – enthralled with the warm affection that defines Joe’s relationship with Marjorie. Arguably, Joe’s character develops into a positive point of contrast to Helen’s Pākehā husband, Gil; where Gil is cold and increasingly distant, Joe is loving, unpretentiously committed to forging a married life with Marjorie and their son that falls comfortably outside the staid small town of Gladston.

Seemingly, Māori broadly fulfil a similar function throughout the novel. Māori life is honest and full of genuine connection (with others, with nature) where Gladston’s Pākehā suburbia is disconnected, shrouded in secrecy and gossip. On a Christmas Eve, Gilbert observes a group of Māori "laughing in their own way, different from the way Dad and the men from the works [laugh]". His immediate response suggests a sort of wistful jealousy: "It would be good to laugh with somebody the way the Maoris laughed." Fittingly, one of the novel’s final moments sees the Cunninghams connecting with Māori from ‘the coast’ on a family holiday. In a climactic exchange, a ‘sage-like’ Māori responds to Helen’s suggestion that he must have less ‘rush and worry’ in his life on the peninsula: "People they always think there is something better around the corner and they talk about this and worry about it but when they get it they find it isn’t so good and they worry for something more around the next corner […] [People] can call me miserable old stinkpot, or they can call me a good fellow, but I don’t care. I’ve got my people, and so I am content."

The old man’s speech encapsulates both the limitations and potential of reading The Cunninghams as a work of Māori literature. While ultimately a positive depiction of Māori, it also smacks of the sort of one-dimensional ‘wise sage’ treatment that many ‘characters of colour’ have suffered in literature – think of what Spike Lee would deem a ‘magical negro’ half a century later. Is this simply a patronising ‘noble savage’ conception of Māori culture? In the hands of another writer, I might say yes, but Ballantyne is just not that easy to pin down.

Consider the very next page, where Helen judges the ‘consumptive’ appearance of the Māori children and deems the old man a "crackpot". This is a complex depiction of disconnected suburban Māori of the era: the sorts of people who might, on one level, identify something missing from their colonised existence but who have been conditioned to look down on Māori who continue to resist the pull of a Pākehā-fied ‘middle New Zealand’.

It's easy to imagine a version of The Cunninghams that is more informed by the politics of the then-coming Māori artistic renaissance, where the Cunninghams are a family on the brink of their own cultural revitalisation. The novel we have is not that, of course, but it is undoubtedly a unique literary relic given its era: a complex, fully-realised piece of published literature by a Māori author that, in part, explores the Māori identity of its characters – and, because of its biographical ties, the Māori identity of the author himself.

It's a shame that Ballantyne’s later works never revisited these concerns with such clarity. The exception could have been a planned novel with many potential titles, including ‘A Polynesian Comedy’. This was to be the follow-up to 1968’s Sydney Bridge Upside Down, and Ballantyne had made the decision to focus on an explicitly-Māori protagonist, an alcoholic public relations worker called Christopher Uhuru Potter. Bryan Reid describes the manuscript as "very strange but ultimately powerful", full of surreal turns and loose ends that feel like a development of the gothic, dream-like atmosphere of Ballantyne’s 1968 classic. ‘A Polynesian Comedy’ stands as one of the more exciting unpublished works of Māori literature; it would have been intriguing to see Ballantyne revisit The Cunningham’s exploration of Māori identity through the bold stylistic reinvention of Sydney Bridge Upside Down. Unfortunately, like many aspects of Ballantyne’s career, it was not to be.

In the 21st century, David Ballantyne continues to be something of a literary enigma. I have to admit that when I first discovered the existence of this largely-forgotten author, I felt disillusioned. I had unearthed an uneasy dilemma: if something like The Cunninghams can be elevated to the status of ‘first Māori novel’, will the retrospective importance of something like Tangi be diminished?

My opinion is, no, I think not. The early works of Witi Ihimaera (and Hone Tuwhare, Patricia Grace, Heretaunga Pat Baker, and many others) are steeped in te ao Māori. They took a people that had, up to that point, largely been viewed in literature as outsiders – often through dispassionate, dehumanising lenses – and set them to life. These foundational works are not only enduring taonga for Māori readers, but also monumental within the broader context of indigenous literature anywhere (in a way that we in Aotearoa are liable to take for granted).

Ballantyne is not that, and a work like The Cunninghams will never occupy such a place within the canon of Māori literature, nor in our collective imagination. It is too flawed, its ‘Māoriness’ a too minor aspect of its narrative. But it is a novel from 1948 in which a Māori writer grapples with Māori identity, even if in a limited way – and Ballantyne’s unpublished work hints strongly at an unrealised passion for exploring this part of himself further. The work of David Ballantyne, therefore, deserves some place within the history of Māori literature – a fitting legacy for a writer who was so often cast off as a literary outsider in his lifetime.

Taken with kind permission from the new anthology of Māori writing Huia Short Stories 15 (Huia Publishers, $25), available in bookstores nationwide. Contributors include the latest successor to David Ballantyne as an important Māori novelist, Airana Ngarewa, whose book The Bone Tree has held the number one position on the Nielsen BookScan chart for nine weeks in 2023.