It was a single reference in a single speech, a top official of East Germany’s feared Stasi secret service boasting about having trained hundreds of “liberation fighters” from “young national states” that year. But to historians, it was one of the rare pieces of evidence linking the agents of the former Communist regime to troubles afflicting the Middle East to this day.

Guerilla fighters in the 1960s and 1970s were flown to East Germany, taken to military sites, including probably the Schoenefeld Airport now used by discount airlines to fly travellers in and out of Berlin.

“They were taught how to hijack planes, plant bombs, stage kidnappings,” says Tobias Wunschik, a historian at Berlin’s Humboldt University. “But they destroyed all such files about these matters.”

Three decades after its demise, the Stasi’s mysteries live on, both in Germany and abroad, with Germans continuing to assess its impact.

Thirty years ago this week the Berlin Wall came down. Within months, protesters and activists stormed the Stasi’s massive Berlin headquarters complex of nearly 40 imposing buildings.

Inside they found buildings full of surveillance equipment and documents showing how the Ministry for State Security ruled over the nation of some 17 million for 40 years. Millions of files, now kept in vaults, showed how networks of spies inside the country, and even in what was then West Germany, kept tabs on their countrymen in order to maintain the rule of East Germany’s Socialist Unity Party.

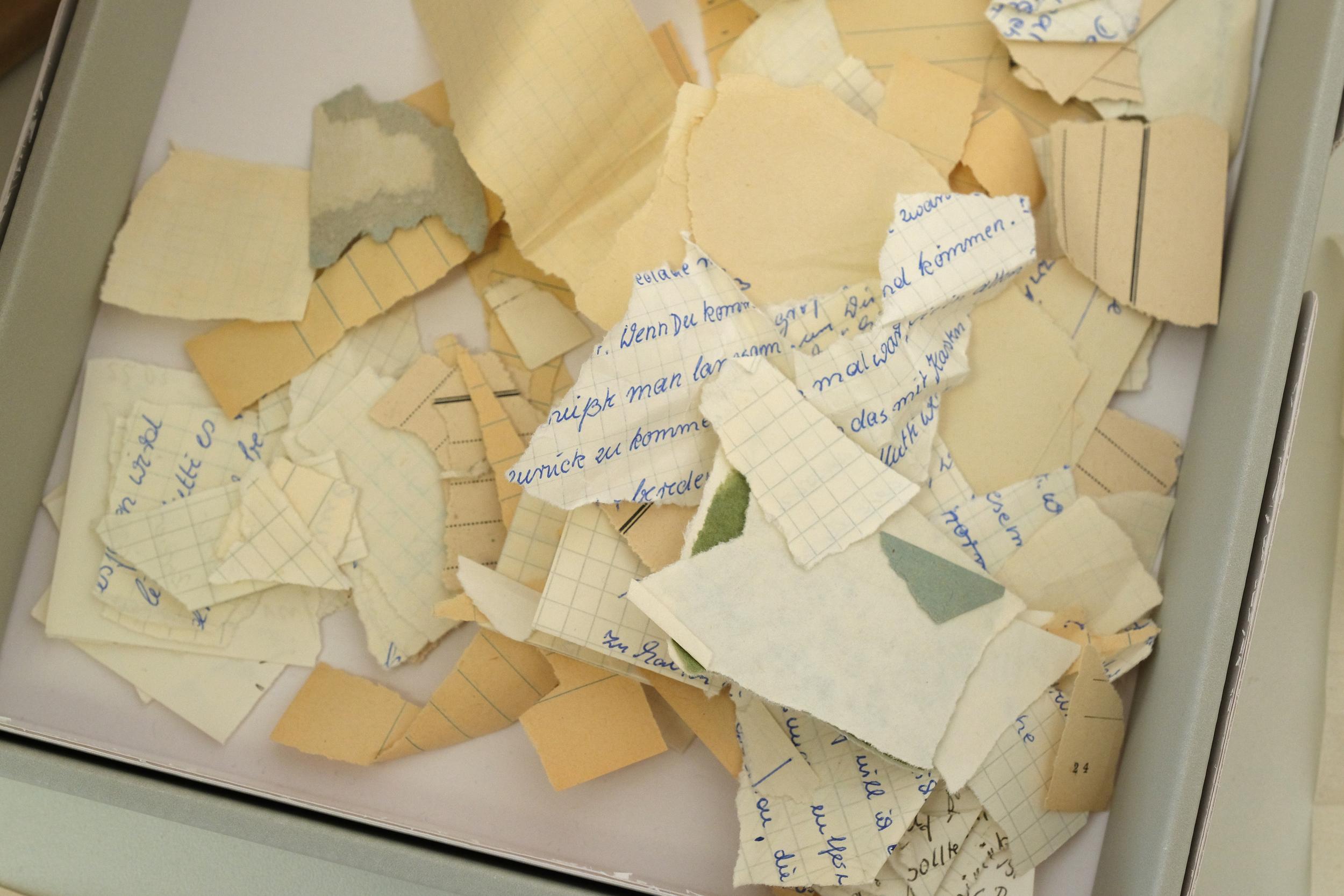

But absent – despite the prim bureaucratic culture having meticulously documented nearly every move of East German citizens – were the files that recounted the Stasi’s history of operations abroad, including its cultivation of secret services in the Middle East. Those files, say archivists and historians, had been systematically destroyed in the last months of the Communist regime, either burnt, shredded, or soaked in liquid – rooms full of their remains were found in the months after the headquarters was seized.

“They destroyed those files,” says Wunschik. “It was the strategy of the Stasi not to be too precise on such matters.”

Over the last three decades, as historians have reconstructed the actions and methods of what was once one of the most secretive and feared intelligence agencies in the world, its role abroad has become clearer, in part as a result of archives in other parts of the world as well as accounts by former members.

Officially, East Germany was in charge of coordinating Soviet efforts with South Yemen, the leftist-leaning separatist entity that was later subsumed into the rest of Yemen. But like its patrons in Moscow, it was also seeking to counter the US and West Germany’s influence in the Middle East, which included support for Arab monarchies in the Gulf and Israel. It provided as yet undisclosed training to security services and armed forces in Syria, Libya and Iraq, which were deemed socialistic brethren, says Wunschik.

Former members of the Stasi have described East Germany as a base for militants such as Carlos the Jackal, Abu Nidal, and Abu Daoud who was accused of being behind the 1972 massacre of Israeli athletes in Munich. In the mid-1980s, concerned about the reputation of its militant clients, it began to scale back support.

“East Germany was extremely concerned about its international reputation, so everything they did they wanted to hide,” says Wunschik.

According to Wunschik, the Stasi trained at least 1,000 members of the officer corps in Iraq, Libya and Syria, and invested heavily in the leftist factions of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation.

But it not only gave its clients training, it sought to actively infiltrate and gather compromising material on them, as well. Both the gardeners and the caretaker of the grounds of the PLO embassy in East Berlin were senior Stasi officers, according to Wunschik.

But perhaps its greatest global legacy is how it perfected now widely used arts of non-violent repression, methods adopted by countries such as Iran and China. Sensitive about its international image and eager to take part in emerging pan-European institutions, it couldn’t afford to torture dissidents with electric shocks and pulled nails that left bruises and scars that could be photographed and published abroad.

“The Stasi reigned for more than 40 years,” says Jorg Drieselmann, a former East German dissident who is now managing director of the Stasi Museum, housed in the dreary former headquarters of the service.

“At the beginning its main task was to pursue and safeguard the power of the party. But once it did that, its main goal was to influence and control 17 million people.”

Over the years as the archives opened, historians discovered how the Stasi used friends and neighbours to spy on each other and collect information, and how it weaponised information to shape and destroy the lives of people without resorting to violence.

Central to its philosophy for controlling the public was a technique it called Zersetzung, or the demolition of personal lives using psychology.

“You were invited for a chat,” says Drieselman. “You’re told, ‘We could put you in jail for five to seven years. Your wife will also be jailed. When you get out of prison, your kids won’t recognise you.’”

Experts say dozens of children of dissidents were adopted by Stasi employees or privileged members of the German socialist party.

But dissidents were also offered a choice. “They were told, ‘If you’re ready to admit that you made a grave mistake, you have the option of removing your heavy guilt. We’ll forgive you. You’ll work for us now. You’re an informant.’”

In addition to 91,000 employees at its peak, the Stasi employed hundreds of thousands of collaborators across the social gamut. All were ordered to spell out the terms of their surrender to the state, writing in longhand that they were now working with the Stasi, serving as an informant, and choosing their own code name.

One informant was Frank Troger, a punk-rock musician who was pressed into informing on the counterculture scene in the early 1980s. Aided by Stasi’s hand, his band, The Firm, later became a minor success, performing even in Western Europe. All the while he kept fear and mistrust alive in the underground music scene by spreading the rumour that the Stasi was seeking to recruit punks.

After the wall came down and the archives were opened, it emerged that another member of his band had also been recruited by the Stasi, perhaps to keep an eye on him.

“When I look at other dictatorships there was a system of fear and repression that worked,” says Roland Jahn, a former East German dissident who is commissioner of the Stasi’s archives, and who led the charge to safeguard them 30 years ago.

“The East German state was not capable of airtight repression. It was very effective in destroying people’s biographies. Through the intervention of the state your life could be changed forever.”

So vast was the Stasi’s empire of power that the three dozen or so buildings that made up its headquarters make up an entire district of Berlin. The buildings that housed it remain standing, used at some point in recent years to house the refugees and migrants that wound up in Germany, but mostly empty now except for a few social services agencies.

The trauma the Stasi inflicted was so deep that Berlin’s authorities over the last 30 years have been unable to decide what to do with the massive properties that stretch roughly a third of a square mile.

Inside the Stasi Museum, curators have preserved the furniture and decor of the secret service’s offices, illustrating the banal surroundings of an agency that damaged so many lives. The settings and milieu will be familiar to anyone who watched the Oscar-winning 2006 film The Lives of Others, which chronicled the story of a Stasi agent, or the hit television series Deutschland 83, about the spy service’s clandestine operations abroad.

Torsten Kahlert is a historian who gives Germans and foreign visitors tours of the Stasi Museum, among the few such institutions in Germany that is run by a collective of activists rather than the state. He tells those younger generations, with no direct experience of the Cold War, that the story of the Stasi remains relevant.

“I wouldn’t say that the Stasi was efficient in all its ways. They claimed to be everywhere but they weren’t,” he says. “And in the end they just collapsed with the whole system.”

But, he says: “You can see a lot of what the Stasi did nowadays. It’s a model for understanding dictatorship and how a society can be controlled by just one organisation.”

Dennis Yucel contributed to this report