In 1965, David Bailey, already Britain’s most fashionable photographer, took a portrait of the gangster twins Ronnie and Reggie Kray, who looked fiercely well-groomed in suits and narrow ties. At the time, they were not the notorious gangsters they were to become, but former boxers who ran nightclubs and collected protection money from people in awe of their reputation as a two-headed fighting machine. The portrait became gangland’s Mona Lisa: copied, pirated and imitated, it was central to their image and their brand. They aspired to be as famous as Al Capone and Legs Diamond, and were gratified when one of Bailey’s pictures of them, with their brother Charles, appeared later the same year in Bailey’s Box of Pin-ups, his document of 1960s celebrity culture, alongside the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Rudolph Nureyev, Lord Snowdon and Jean Shrimpton. “Their big mistake was posing for me,” Bailey told the BBC last year. “If you’re a real gangster nobody knows who you are.”

The Krays, of course, wanted everyone to know who they were. They may have been failures as professional criminals, but by the time they were sentenced to life in prison at the age of 35, their brand was already a phenomenal success. They spent half their lives behind bars. Ronnie died aged 61 in Broadmoor in 1995, and Reggie, released very briefly from prison on compassionate grounds, in 2000. Nonetheless, all these years later, the fascination with their story remains undimmed.

An extraordinary Krays revival is now under way. The film Legend, starring Tom Hardy as both twins, has its premiere today, and it opens in cinemas next week. A new documentary, The Krays: the Prison Years, featuring some of their surviving henchmen, will shortly be shown on the Discovery Channel. Another documentary, The Krays: Kill Order, is released on DVD next week. Last month another film, The Rise of the Krays, was released on DVD and later this year its companion, The Fall of the Krays, will arrive. There have been more than 50 books by or about the Krays; the latest, published this summer, was One of the Family, by Maureen Flanagan, a former Page 3 model who used to cut their mother’s hair. A weekly tour of their old stomping ground will start as usual this Saturday at the Blind Beggar pub in Whitechapel, east London, where Ronnie murdered George Cornell in 1966, although it does not yet extend to the Stoke Newington house where Reggie killed Jack “the Hat” McVitie the following year. Their coshes, knuckledusters and crossbows – part of their collection of antique and curious weaponry – are on display in a museum in Gloucestershire and there is currently an exhibition in Bethnal Green, entitled Legend of the East End (to tie in with the new film), where you can see Ron Kray’s dinner jacket, spectacles and ring in a glass case. Memorabilia including gypsy caravans made by Ronnie out of matchsticks and naif paintings of boxers by Reggie, now sell for thousands of pounds on eBay. Bailey’s famous image appears tattooed onto a man’s calf in another of his portraits, currently on display at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh.

The twins were fascinated by the movie mobsters of their cinema-going childhood; their role model in England was a dashing gangster called Billy Hill, who in the 1950s exercised the same control over Soho as they would later over the East End. Hill modelled himself on Humphrey Bogart, holidayed in Cannes and owned a club in Tangier, where the twins visited him in the 1960s and were impressed by his set-up. One of Hill’s friends was the crime reporter Duncan Webb, who ghosted his 1955 autobiography, Boss of Britain’s Underworld. If Bailey’s photo was the first stage in the construction of the Krays’ enduring image, stage two came in 1967, when the Krays approached John Pearson, a journalist who had just written a well-regarded biography of Ian Fleming, and asked him to be their biographer, focusing on their clubs, their celebrity chums and their charitable works. (Truman Capote, who had just published In Cold Blood, had been their first choice, but he declined the commission.) Pearson’s The Profession of Violence, published in 1972, three years after the Krays were jailed for life, played a major part in the creation of their image, both through the richness of its prose and its unadorned revelations about their crimes.

Throughout the late 1950s and early 60s, the Krays were carving out their reputation – sometimes literally – which they used both to make money and win attention. In 1954, they had taken over the Regal billiard hall in the East End, where Ronnie attacked members of a Maltese gang with a cutlass after they foolishly tried to extract protection money from him and his brother. Word spread about their capacity for violence, as there were always many witnesses to their beatings and carve-ups.

By 1957, they had their own club, the Double R, and their own gang, known as “The Firm”, consisting of a mixture of London heavies, Scottish hard men and bent businessmen. Gossip about the sheer scale of their violence travelled far – Ronnie branded one miscreant, the jewel thief Lenny Hamilton, with a white-hot poker for breaking the nose of a Kray associate – and ensured that they always got what they wanted, whether it was a percentage of a club’s takings, protection money from a pub or business, or a slice of another criminal’s robbery proceeds. They moved westwards, taking over a gambling club, Esmeralda’s Barn, which initially made them thousands of pounds a week. They felt like they were in the big time, even though the bank robbers of the era looked down on them as mere bullies, called them “thieves’ ponces”, and “Gert and Daisy” behind their backs, claiming that they didn’t steal their own money and attracted too many dodgy hangers-on.

George Cornell, a gangster from south London, had called Ron a “fat poof” – Ron used to say “I’m homosexual but I’m not a poof” – and once, when Ron was drunk, had beaten him up. Ron was already suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and, on 9 March 1966, when he heard that Cornell was in the Blind Beggar pub, which was on the Krays’ patch, he went round and shot him dead in front of shocked witnesses. The following year, Jack “the Hat” McVitie, who had also caused the twins some minor grief, was persuaded to attend a party in Stoke Newington, north-east London, where Reggie stabbed him to death, again in front of numerous witnesses. They thought their reputation made them untouchable, but the police, under Detective Chief Superintendent Leonard “Nipper” Read, pursued them doggedly. The Firm started to fall apart as its members gave in to police pressure and informed on the twins.

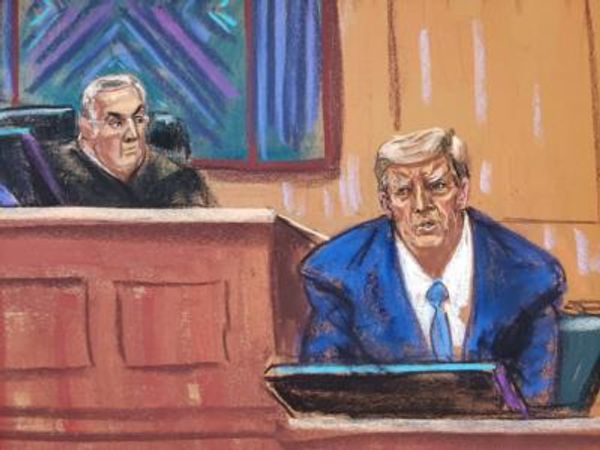

In May 1968, Ronnie and Reggie Kray were arrested. Their Old Bailey trial the following year was, at 39 days, the longest murder trial in English legal history at that time; the press and public galleries were both packed. The twins denied everything, but the Blind Beggar barmaid, thereafter known as “Mrs X”, gave damning evidence and the renegade members of The Firm did the rest. Ronnie gave a spectacular but crazed performance in the witness box, name-dropping the boxing champions they knew and portraying himself as an innocent East End philanthropist. They were jailed for life and a minimum of 30 years by Mr Justice Melford Stevenson, who told them that “society has earned a rest from your activities”.

There was to be little rest from the twins, who continued to promote their image as England’s No 1 gangsters so diligently. And that remains the great enigma about the Krays: the fame they craved ensured that they would be a target for the police, and yet they staged their crimes where they would be guaranteed an audience; the men they believed were totally loyal were the ones who ensured their downfall. Once jailed, they devoted their considerable energies to their image as gangland stars, always open to visitors from outside. Their criminal empire may have been built on sand, but their name became a brand that retains its potency to this day for a nation both fascinated and repelled by the transgressive.

* * *

“Ronnie used to say ‘you should have been in my gang’, because I had – what is it? – that forceful personality,” Maureen Flanagan said when we met in July at her home near Broadway Market in Hackney, east London. Like many of the twins’ circle, Flanagan walked the line between the worlds of entertainment – she was a topless model, appeared in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the Likely Lads and the Benny Hill show – and crime, as the confidante and surrogate little sister of the Krays. Her memoir, One of the Family, was launched with a party at the Blind Beggar in July. She recalls how the Kray franchise established itself: how they used the notoriety from the trial, the kudos from the Bailey portraits and the lurking menace they still inspired, despite their incarceration, both to make money for their prison comforts and – even more important to them both – to ensure their immortality.

Flanagan, who goes by her last name, was Violet Kray’s hairdresser and first met the twins when they were polite young men popping in to see their beloved mum. After Violet died in 1982, Flanagan took on the role of prison visitor and go-between with the press. In the meantime, she had become a model, encouraged to enter the business by another young working-class photographer, Don McCullin, who had started to make his own name by taking moody pictures of young would-be gangsters for the Observer. “He told me I looked like Shirley Eaton in Goldfinger and did my first modelling shots,” said Flanagan, now 74. “I had fabulous legs so it always had to be in short skirts – sexy nurse, sexy secretary and so on. I was in Monty Python’s Hell’s Grannies and chased round trees by Benny Hill.”

She describes the matriarch, Violet, as the classic gangster’s mother, proud of her boys: “There’s nothing wrong I could say about this lovely lady except that she totally spoiled them from birth.” Flanagan did Violet’s hair at her home in Vallance Road – “Fort Vallance” as it became known – in east London because if she came to the salon, Violet, sitting under the dryer, would be pestered by people wanting the twins to “have a word” with someone on their behalf.

By 1965, the twins had figured out how to turn their fearsome reputation into a source of income. “The protection racket was their game,” said Flanagan. “But it wasn’t just for money, it was for prestige, status. Ronnie loved celebrities. They brought over Joe Louis, the former heavyweight champion of the world, and they would take him round the clubs and make him sign boxing gloves for people. Ron liked being in the company of George Raft (the American actor and star of the 1932 film Scarface, who was a director of the Colony Club, a West End casino). Then Judy Garland was in town and she had sung their mother’s favourite song (Somewhere Over the Rainbow) so the next thing for Ronnie was, ‘We have to have Judy Garland in our presence’.” Garland was duly invited to tea with Mum, who was a little underwhelmed. “She was a frightened little thing, too skinny,” was Violet’s verdict. (At his trial, Ron cheerfully told the judge, “If I wasn’t here, I could be having tea with Judy Garland.”)

British actresses Diana Dors and Barbara Windsor were also courted by the Krays and photographed with them. This cross-fertilisation between crime and showbusiness, exemplified in the US by Frank Sinatra’s relationship with the mafia, had benefits for both sides: prestige for the gangsters, edgy cool for the stars. Carried away by the ease with which the famous responded to their approaches, they summoned their high-profile biographer. “They thought they would come out as good guys,” said Flanagan.

Flanagan visited the twins in prison faithfully, dealing with Ronnie’s demands from inside Broadmoor, which included smoked salmon from Harrods and bagels from Brick Lane, plus gifts for the young prisoners who took his fancy. One of Flanagan’s roles was to ring the Daily Mirror from a phone booth outside Broadmoor after a visit with titbits about Ron. The paper would pay anything from £50 to hundreds of pounds for a story, depending on how big it was, and Flanagan would pass the money to their big brother, Charlie, who would share it with the twins; Flanagan would get a “finder’s fee”. Broadmoor was a secure hospital rather than a prison, and the canteen could be used by inmates to order in expensive items from the outside world which were put on tick. At one stage, Ron’s canteen bill stood at £7,000.

Ron’s largesse was one of the reasons that the Krays needed to capitalise on their name, and among the handy earners was the selling of media rights to his two weddings. In 1985, he wed Elaine Mildener, who had been writing to him in Broadmoor – as did many women – and visited him with Flanagan. Ron had been told that the Sun would be the best payers and a fee of £20,000 was agreed – although only £10,000 was eventually paid. This gave the paper access to the wedding in the Broadmoor chapel.

Elaine soon found that her role mainly involved running errands for “the Colonel”, as he was known, and they divorced in 1989. She was swiftly replaced by a self-confident former kissogram girl, Kate Howard. The press were informed that they could have a “brief interview” with her, plus wedding photos and guest list: “all offers for this exclusive to be in by 10 October and in excess of £25,000.” The new bride, “bubbly blonde Kate”, soon appeared regularly in the tabloid press. That ended in divorce in 1994, but Kate Kray has done well out of the union: she has since written 19 books, mainly about gangsters, under her married name.

Reggie’s first wife, Frances Shea, committed suicide in 1965. In Maidstone prison in 1997 he married 38-year-old Roberta Jones, from Southport. When I met her at her home in Norfolk at that time, she was conscious that, by marrying a Kray, she had entered the media spotlight: “It scares me. You are always aware that you might say something wrong.” As with Kate, the Kray name opened the publishing house doors for Roberta. Eleven crime novels, with titles such as Bad Girl, The Villain’s Daughter and No Mercy, have followed, with the word “Kray” featured prominently on the cover.

Another of Flanagan’s tasks, when the twins were in prison, was to help them organise charity events to which their name would be attached and which were a key part of their image. She would be tasked with getting George Best to sign a Manchester United shirt, or the former world welterweight champion John H Stracey to sign boxing gloves, which would be raffled or auctioned. The Krays always took a good slice of the door money for any charity event.

While their older brother, Charlie, was on the outside, he was expected to manage the brand. The brothers set up a company called Krayleigh Enterprises, which merchandised their name with everything from T-shirts – “Kray Twins on Tour” – to cigarette lighters. Equally lucrative was the sale of their name to small security firms, who would pay a few thousand pounds to be able to tell clients that they had the Krays’ backing. The Krays’ business cards still described them as “personal aides to the Hollywood stars”. Fifteen years after they were sent to jail, they provided bodyguards for Frank Sinatra when he visited Britain in 1985.

* * *

It is not difficult to see why the Krays wanted Chris Lambrianou in The Firm. A big, bearded bear of a man (left), Lambrianou is an imposing presence. He was jailed for 15 years for his part in the McVitie murder, along with his brother, Tony, who died in 2005, having published a bestselling memoir, Inside the Firm, in 1991. Lambrianou, now 76, had a vision in prison, became a born-again Christian and, after completing his time, took a very different path. His own book, published in 1996, was titled Escape from the Kray Madness.

“I wrote the book for money. I had five children and I’d just come through an aneurysm and didn’t know how long I had to live,” he said. He had already turned down offers from the Daily Mail and £50,000 from the News of the World. “Everybody wrote a book. I couldn’t recommend one, to be honest, so many people jumped on the bandwagon. I think Tony’s was fairly accurate.”

Lambrianou’s spiritual conversion led him to work at the Ley Community, a residential rehabilitation centre set in five rural acres in Yarnton, Oxfordshire, which helps people escape from addiction, including many referred from the courts or prison, and where he still has a voluntary role and is clearly regarded with affection. Before we sat down to talk, he arranged for a young resident of the place, a former heroin addict, to give me a tour of the immaculately clean, tightly run premises.

“If the Krays are a legend, it’s a very sad legend,” Lambrianou said, as we sat outside in the sun and watched the residents head across the lawn into a group meeting. “They literally did nothing apart from be twins who got themselves into some tremendously sticky situations they couldn’t get out of. I think Reggie would have loved to have walked away and Ronnie, well, Ronnie liked things and he liked to give things away. He was a very generous man but they gave their souls away.”

On what turned out to be a fateful day, 28 October 1967, Lambrianou arrived with McVitie at what they thought was going to be a party, but was in fact a trap. Reg and Ronnie were waiting for McVitie. Reg tried to shoot him but the gun jammed, so he stabbed him to death. Lambrianou had left the house before the killing, dismayed at what was under way, but returned to pick up his brother, and had to help clean up. He recalled carrying a bucket of blood upstairs and waiting until all was clear at the all-night bagel shop across the road so they could carry the body out in a blanket. “People tell you you can put a body in the boot – you can’t – it was on the back seat.” They took it south of the river and left it. “Whatever happened to the body after that, I have no knowledge.”

At the Old Bailey trial, there were so many defendants in the dock that the judge had numbered cards hung round their necks so the jury could identify them. Lambrianou threw his card across the court, and Ronnie Kray shouted out: “This is not a cattle market.” The judge backed down on the labels but held firm when it came to sentencing. Lambrianou did his 15 years, read voraciously – Khalil Gibran, Krishnamurti – listened to music – Van Morrison, Pink Floyd – and found God.

We looked at an artist’s impression of the 10 men in the dock which is reproduced in Lambrianou’s book and which had been drawn, during the trial, for the Daily Mirror by Oliver Williams. Half of them are dead now. “So many innocents got caught up. It was a tragedy of errors. I felt guilty because I chose the code over my family. Why would I do that? Because I didn’t see myself working anywhere else.” He has seven children now and lives not far from the Ley. “The Kray name means nothing to them, they’re hardworking people. Back in the day we looked up to gangsters like Dillinger, Al Capone, Legs Diamond, Bonnie and Clyde, that was what they fed us on, the American films, and I think the British press wanted something like that in this country.” Because the papers needed a good gangster story, the Kray connection meant money for anyone who could sell a story about them. Lambrianou recalled a tennis doubles game in prison – “gangsters versus robbers” – during which he and the great train robber Bruce Reynolds had an altercation. News of it was in the papers the following day: “They paid the screws.”

As to the enduring Kray brand, he’s baffled. “Eventually they’re going to be Robin Hood – which they never was. They stole from other villains and, if a man was starting a club and making a living, they went in and took it off him – and they never gave it back to the poor. They spent it on clothes, drinks, giving stuff away, holidays, their place in Suffolk (a fancy country pile sold to pay for the legal costs). They didn’t look after anybody.”

* * *

The relationship between the twins and the press has been spectacularly symbiotic. Both sides have profited handsomely from an affair that properly began when the front page of the Sunday Mirror on 12 July 1964 read: “PEER AND A GANGSTER. YARD INQUIRY.” The unnamed peer was Lord Boothby, a Tory politician and television personality, who was attracted to rough trade at a time when homosexuality was still illegal and liked to hang out with Ron, whose acolytes knew him as “the Queen Mother”. This was followed by another story, which referred to “the Picture We Dare Not Print” – of Ronnie and Boothby – which still did not name the latter. Boothby wrote an unblushingly dishonest letter to the Times in which he claimed that “the whole affair is a tissue of atrocious lies”, sued the Sunday Mirror for libel and pocketed £50,000 in a settlement. John Pearson suggested in Notorious, published in 2010, that Boothby paid £5,000 to Ronnie on the tacit understanding that he would keep quiet about their association.

Amid the frisson surrounding this case, the Sunday Times commissioned Bailey to take the celebrated portrait to accompany an article by Francis Wyndham, who recounted that “to be with the Twins is to enter the atmosphere (laconic, lavish, dangerous) of an early Bogart movie”. The article did not appear but his words accompanied Bailey’s Box of Pin-ups; and That Photo has been a mighty earner for Bailey, too.

Behind bars, both twins were generally receptive to press inquiries. I was introduced to Ron by a former inmate who had been a friend in his earlier prison days. He was cordial and talkative when I visited him in Broadmoor in the 1980s, even though there was no money in it for him. Conscious of his image, he was as immaculately dressed as always – pastel blue suit, blue and white shirt and tie, monogrammed handkerchief, cufflinks, gold bracelet, diamond ring; he was fitted for a new suit every year by a tailor who went to Broadmoor to take his gradually expanding measurements. He drank non-alcoholic Barbican lager and chain-smoked John Player Specials and talked about where he would go if ever released – “Morocco, for the boys”. He added, “Don’t print I’m mad.”

Reggie was a prolific writer of letters to journalists and was also happy to be visited, usually in advance of a project or a book he was about to launch. At one point, he told me about his plans for an exercise manual for people confined to small spaces. He also contacted me when I worked for the London Daily News to suggest that I interview an aspiring pop singer and ex-con called Pete Gillett, whom he described as his adopted son. Reg kept reporters informed of any books he was writing himself. In a slim volume of his writings from prison, Thoughts, published in 1991, he wrote that “my eventual aim is to be recognised, first as a man and eventually as an author, poet and philosopher.”

Many of the stories about the Krays inside were paid for by the newspapers, the money either going to the brothers and their representatives in the outside world, or to prison officers and fellow prisoners who would sell information about them behind their backs. No tale was too implausible, or marginal. When Nelson Mandela was released in 1990, the Sun put the event in context with a story headlined “If Mandela can get out, so can Reggie!” The story was that “former gangland boss Ronnie Kray reckons the release of Nelson Mandela could herald freedom for his twin, Reggie.”

The Blind Beggar pub has done well out of the Krays, too. There may be no blue plaques in Vallance Road to commemorate their lives there, but there is a red plaque in the pub, courtesy of the manufacturers of the Famous Grouse, to celebrate the fact that it is one of “The Famous 100 – once London’s most famous pub” because of the murder; the “Famous 100” idea won Campaign magazine’s media award in the alcoholic drinks category in 2011, alas, too late for the Krays to claim a percentage. When I visited in July, an off-duty chief inspector from Sussex police was giving a talk on the Krays to a dozen impressed visitors. You can take a selfie in the place where Cornell was shot and the pub sells Krays DVDs for £20 and a Krays Walk booklet for £3.

The weekly walking tour of Gangster London starts there. No film has added more to the British gangster ethos than Guy Ritchie’s 1998 Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, so it is appropriate that the man who conducts these tours is the actor Stephen Marcus, who plays “Nick the Greek”. He takes up to 30 people at £20 a pop on the two-hour tour, some from as far away as Australia and the United States. “They were violent and not very good criminals,” said Marcus, who first thought seriously about the Krays when he was sharing a house with an actor friend who played Charlie Kray in the 1990 film The Krays. “I don’t try and glamorise it.”

Round the corner from the Krays’ old home, on Bethnal Green Road, is Pellicci’s cafe, which was started by Tuscan immigrants in 1900 and remains in the family. Nevio – known locally as Neville – Pellicci, who used to make the twins’ breakfast when they arrived after a night at one of their clubs, died seven years ago but his son, also Nevio, runs what is still regarded as one of the best caffs in the East End, which to this day attracts its share of Kray pilgrims. Nevio is an entertaining presence himself. His father had told him: “They were gentlemen and they looked the business, always very well dressed. If there was an old lady in the cafe, they would pay for her meal. Some months, you get four or five people who come in because it’s where the twins used to eat. That was their table there (on the left at the back, tucked behind the counter.) They used to send us pictures of little houses that they’d painted in prison and they sent my sister, Bruna, a teddy bear.” Buying tea for old ladies is, of course, an endearingly traditional piece of gangster PR; and the Krays always made sure that the local papers were aware of their donations to the local Repton boys boxing club.

Not that the Krays industry is restricted to London. In the Littledean Jail museum in Gloucestershire, the Crime Through Time exhibition carries a range of Krays weaponry. “The rarest piece is Ronnie’s knuckleduster,” said Andy Jones, the museum’s owner and curator. “I have some of their original coshes and one of their crossbows.” In the museum, which Jones described as the largest of its kind in Europe, you can also find Ronnie’s comb, specs and cigarette case. A former punk rocker, Jones came into contact with the brothers when Reggie wrote to him from Maidstone prison, having learned that he ran a crime museum. “They wanted to be immortalised in a private museum rather than in Scotland Yard’s black museum (now renamed the Crime Museum),” said Jones, who then visited Reggie. “I had to give an undertaking that none of the items would ever be sold. The interest in them is timeless. I can’t say why, it’s really part of folklore. There is more of a fascination among the ladies, they like a villain, I think. Criminals today don’t want to be known, they’re like ghosts.”

* * *

Ronnie and Reggie had both been deeply impressed by two films, Bonnie and Clyde and In Cold Blood, that came out in 1967, just as their empire was starting to implode, and they fancied an equally stylish treatment of their own villainy. Their careers were cut short, but they had already inspired filmmakers. In 1971, Villain, directed by Michael Tuchner, starred Richard Burton as a gay and violent gangster just like Ron, whom Burton, under an assumed name, visited in Broadmoor. The previous year, Performance, directed by Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg, featured a gangster played by James Fox, who visited Ron in Brixton prison to prepare for his role.

There were stage versions of the Kray twins, too. In 1972, Howard Barker wrote Alpha Alpha, featuring “Mickey and Morrie Kersh”, who have a flirtation with the establishment in the shape of “Lord Gadsby” and, as critic Steve Grant put it in Time Out, “In a powerful if strained climax, Gadsby has an orgasm while the twins kill their doting mother.” In 1977, there was even a musical, England England, written by Snoo Wilson, with music by Kevin Coyne. Bob Hoskins and Brian Hall played the twins, “Jim and Jake”, and Dusty Hughes directed.

The first film that bore their name, The Krays, came in 1990, written by Philip Ridley and directed by Peter Medak. One of its early scenes is in a hospital where Violet, played by the late Billie Whitelaw, is unimpressed by the young doctor treating little Ronnie for diphtheria. “You’ve done bugger all,” she tells him and adds “bollocks to the lot of you,” as she takes her boy back to Vallance Road. The Krays were furious that Violet was shown using bad language, but they were well-rewarded for the film; £255,000 went to the twins and their big brother, Charlie, who acted as a consultant.

When the Krays was released, the newspaper Today informed its readers that “We will not become a pawn in the publicists’ tasteless game … We will not carry a review of the film or interviews with any of the people involved in the project.” The fact that the film was made with the twins’ full cooperation was a clear indication that their brand was more important to them than their freedom; had Reggie been serious about getting parole, he would have been obliged to express regret for the murders and keep a low profile.

In addition to the films, there is a new television documentary, The Krays: the Prison Years, narrated by Terence Stamp and directed by Matt Blyth. In it, their former Firm friend, Freddie Foreman, and others suggest that, had not the Krays been arrested, they were due very shortly to be murdered themselves: “it was only a matter of months before the pair of them would have been found on a pavement somewhere.” And Patrick Fraser, son of gangster “Mad” Frankie Fraser, notes that “we’ve always thought that they made more money in jail than they ever did when they was out of jail.”

Released as a DVD at £7.99 just ahead of Legend is The Rise of the Krays, to be swiftly followed by The Fall of the Krays, shot at the same time. “We were working on it from three years ago, well before Legend was announced,” said their producer Craig Tuohy, whose own connection with the twins is that his parents met at one of their clubs. When news of Legend emerged, he said, they considered whether to junk the project or ride with the publicity that a Tom Hardy film would generate and decided on the latter. Filming lasted 10 weeks with a large, mainly unknown cast and budget below £5m. Tuohy has seen Legend: “It’s brilliant, but it’s not the true story.” The driving force behind the Rise and Fall are, appropriately enough, two East End brothers, Ken and Terry Brown, self-made property millionaires. David Sullivan, the joint chairman of West Ham football club and former pornographer, is executive producer. “Our film is violent,” said Tuohy, who does not feel it glamorises the twins. “It doesn’t look like a life anybody would want.”

So the Kray franchise is still generating the sort of attention, and money, to which they always aspired. To publicise Legend, there is an exhibition at a gallery on Bethnal Green Road, “depicting the softer side of Kray life ... visitors will be able to enjoy a cup of tea in a replica of Violet Kray’s living room featuring family photos and 60s wallpaper, whilst experiencing an audio-visual installation of interviews with local people who knew or have knowledge of the Krays.” The exhibition carries a statement from the film’s director, Brian Helgeland: “The East End is now a very different place where enterprise and design meet and the Krays have slipped into the alchemy of legend.” In July, he told the Guardian that he thought Reggie would consider his film fair and that Ronnie would enjoy being played by Tom Hardy. “So, yeah, all told they would dig it.”

Of course they would. And they might echo the words spoken by their hero, the gangster Legs Diamond, in Harvey Fierstein’s 1988 musical of that name: “I’m in showbusiness, only a critic can kill me.”

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.