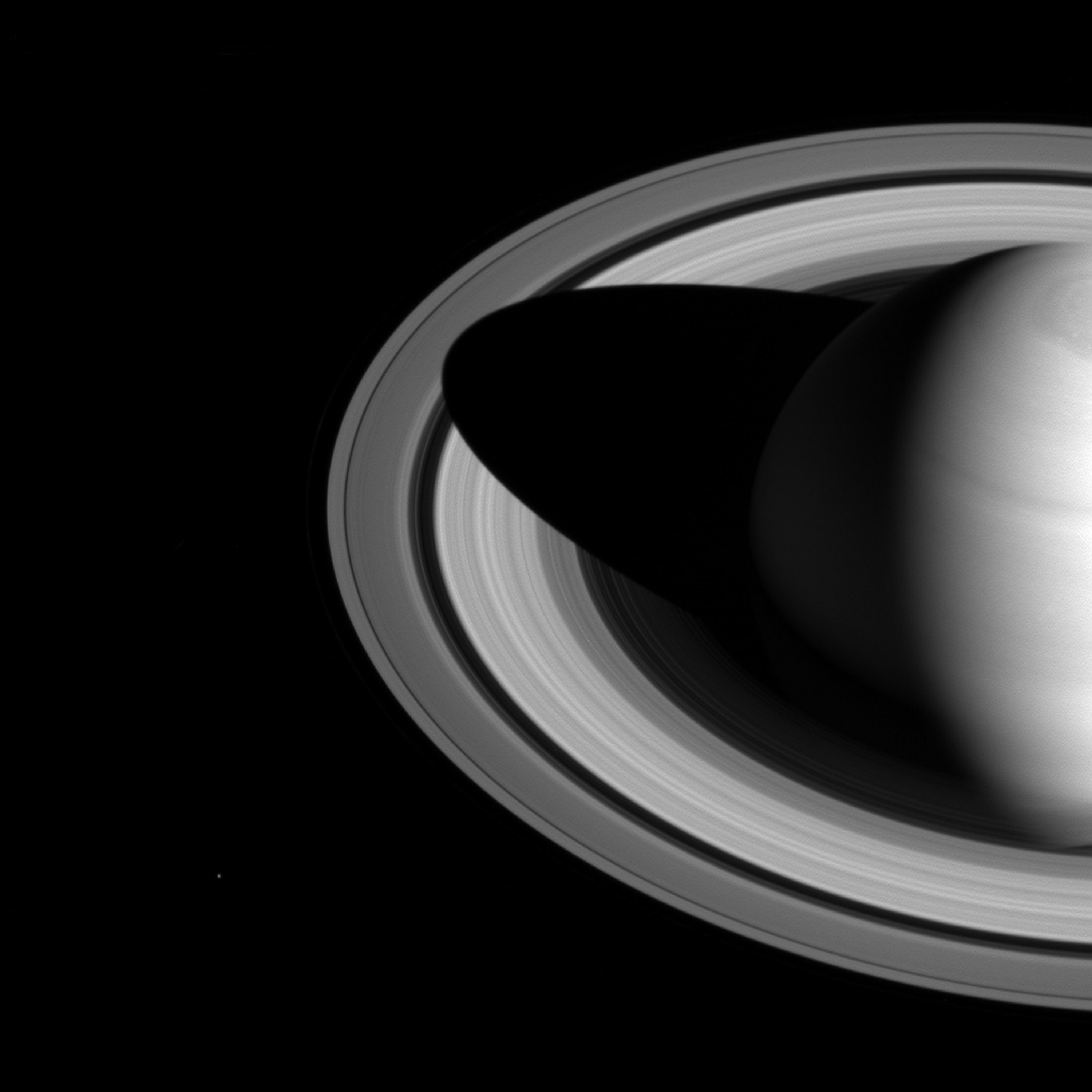

In 2017, the Cassini spacecraft barrelled toward Saturn for the final time. NASA officials had elected to terminate the mission in a death dive. Obliterating the probe in a controlled maneuver would safeguard Saturn’s precious rings, moons, plus whatever else Cassini’s Earthly material could damage, or even contaminate. Like, perhaps, life.

Currently, scientists have never detected biosignatures in another world. But space exploration is providing tantalizing ideas. The latest such notion comes from a frigid moon of Saturn. The work is detailed in a study published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy.

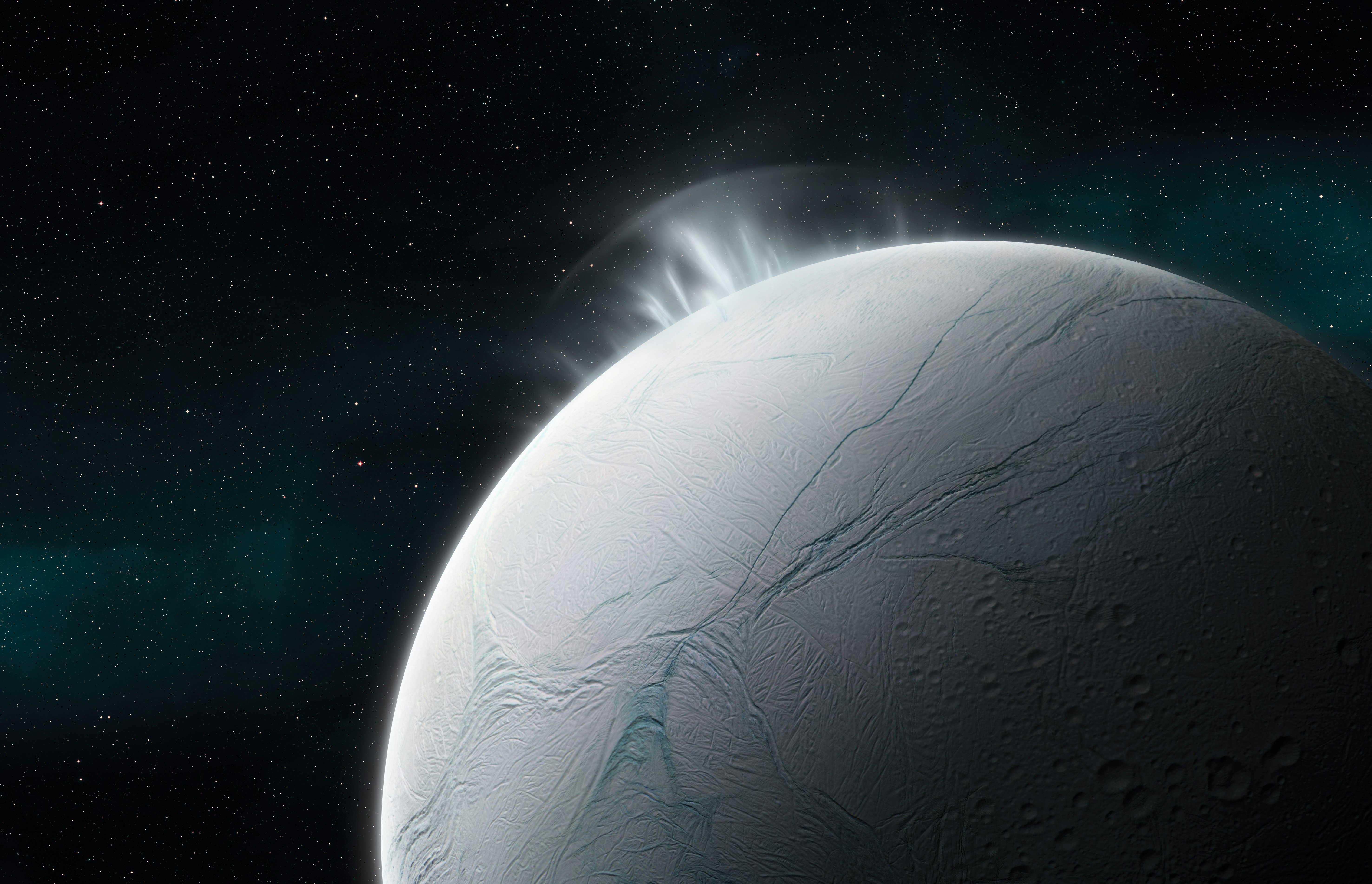

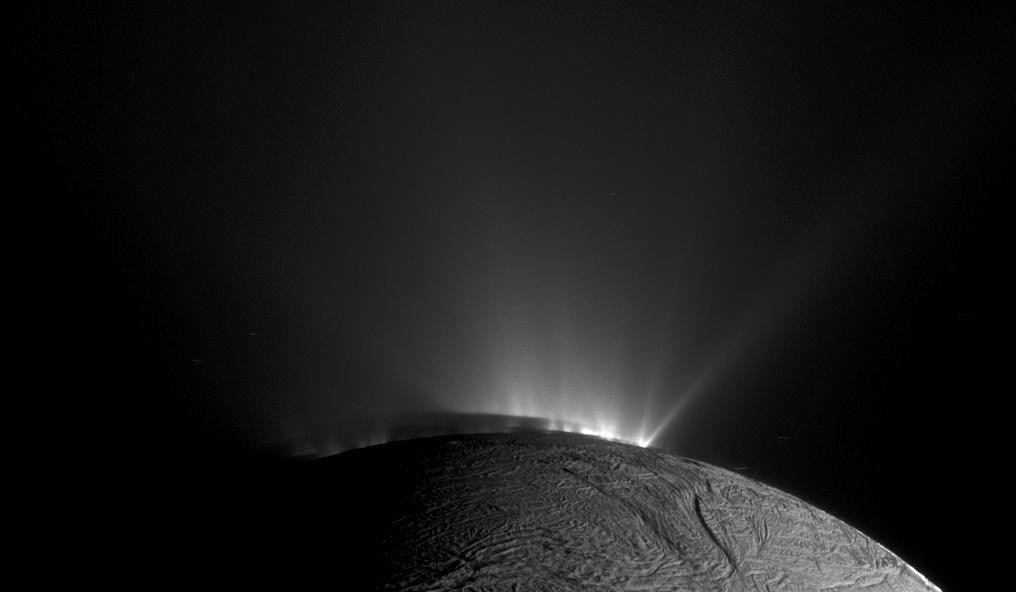

Six years before its fiery finale, Cassini flew through plumes of gas coming from Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The spray was coming through cracks on its icy surface. It was a natural delivery service, giving Cassini’s INMS, or Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer, a special taste of what’s inside the moon.

What’s in the spray?

Astronomers have been studying INMS data since Cassini’s 2011 and 2012 rendezvous of the plumes. So far, they’ve found compelling evidence that Enceladus may have conditions favorable to life. Inside the gaseous spray there was the presence of water, carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia, and molecular hydrogen. This suggests that life could potentially emerge far away from the Sun in another part of the solar system.

But that’s a big maybe. “We don't yet know how life originated on Earth, so it's difficult to say what the necessary conditions would be on Enceladus,” Jonah Peter, a graduate student at Harvard University and lead author of the new paper, tells Inverse.

Life, at least as we know it, requires an energy source.

“The ocean on Enceladus is covered by a thick ice shell, so sunlight is unlikely to provide enough energy for life underneath. That means for life to exist on Enceladus, there must be an alternative source of energy,” Peter said.

Chemical reactions are known to support microbial communities in the dark depths of Earth’s oceans, however.

Tasting the salty Enceladus sea

The team performed a statistical analysis to find what might be hiding inside Cassini’s INMS data. It was built upon earlier work on the plume data.

“Searching for compounds in the plume is a bit like putting the pieces of a puzzle back together,” Peter said. It’s a search for the “right combination of molecules” that would create the data Cassini gathered more than a decade ago in the outer solar system.

Peter’s team found five new compounds inside the plume: alcohol (methanol), molecular oxygen, plus three organic compounds called hydrogen cyanide (HCN), acetylene (C2H2), and propylene (C3H6).

These molecules are not biosignatures, meaning they don’t indicate that life exists on Enceladus. “They do, however, indicate conditions favorable for organic synthesis, which could lead to the formation of more complex molecules related to the origin of life,” Peter said.

One compound in particular, HCN, is a versatile building block of life. It goes into forming amino acids, sugars, and nucleobases. These are the precursors to proteins and DNA.

They indicate that Enceladus’ subsurface ocean has the ability to contain a diverse array of chemical reactions, acting in the Sun’s absence to provide energy for life. It’s an exciting finding, but like most things that thrill, more insight is necessary.

At least Cassini, reduced to a tattered mess of tiny bits in Saturn’s sky, lives on in the data.