Gore Vidal said that he hoped to be remembered as “the person who wrote the best sentences of his time”. It was a typically vainglorious boast from an author whose finest writing remains overshadowed by his reputation as one of the most waspish and spiteful public figures in recent memory.

Vidal, who was born Eugene Luther Gore Vidal Jr at the West Point Military Academy on 3 October 1925, wrote 25 novels, 14 screenplays, eight stage plays and 26 works of nonfiction, including his majestical essays. He was also a master of the insulting one-liner. Most of the obituaries that followed his death on 31 July 2012 featured his celebrated epigrams, such as: “Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.”

His grandfather was renowned senator TP Gore and his father, Eugene, was director of air commerce under President Franklin D Roosevelt. Vidal loathed his mother Nina, whom he described as a bullying, self-pitying alcoholic. After divorcing Vidal’s father in 1935, she married Hugh D Auchincloss, the stepfather of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Vidal never missed a chance to bring up his connections to the Kennedys. He made few close friends at Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire and was described as the class “hypocrite” in a poll of fellow students. At 17, he enlisted and served as first mate of an army freight-supply ship, describing his war experiences as “strange, not lovely and cold”.

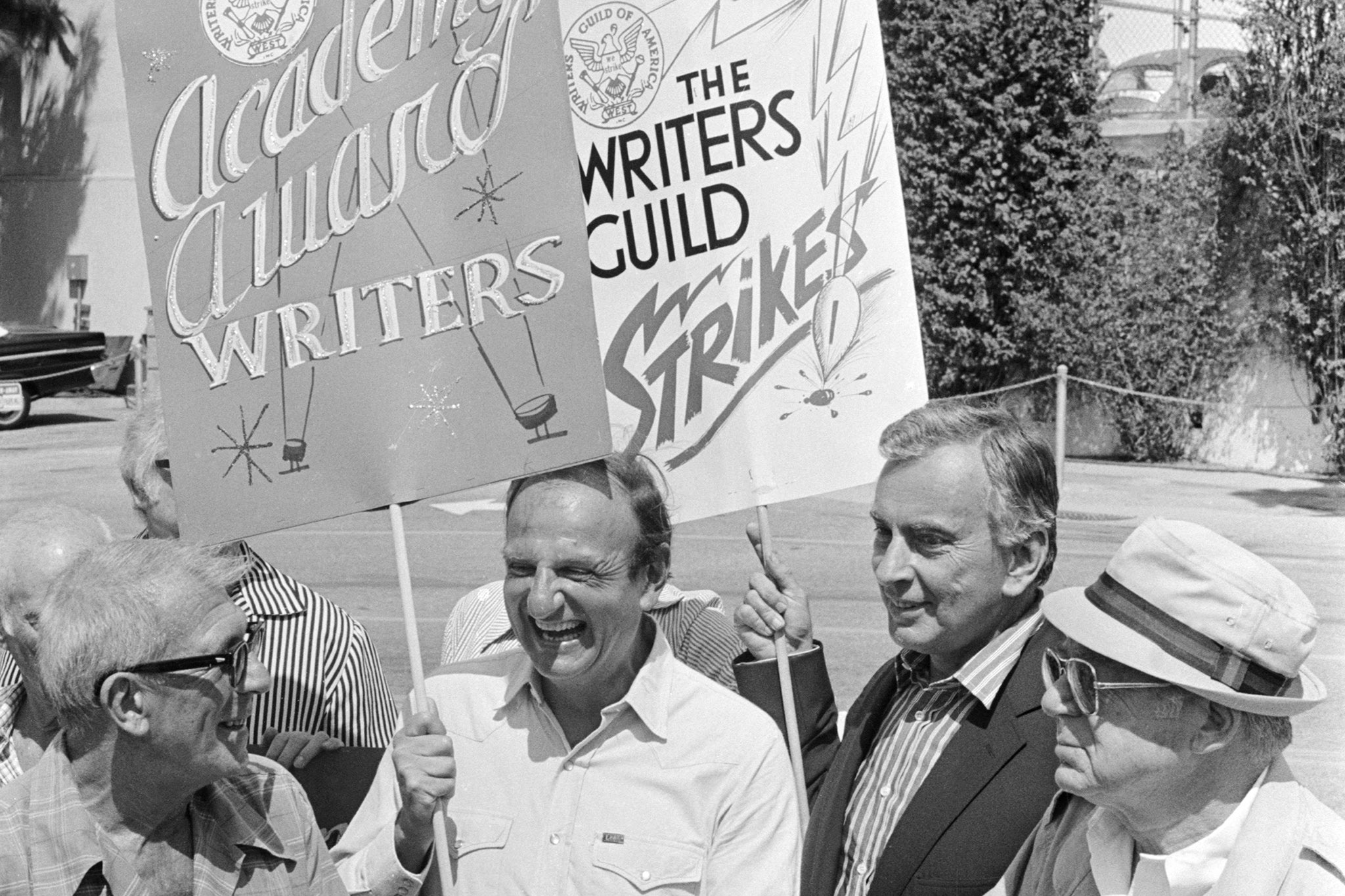

Army service gave him material for a novel, however, and his life in the public eye began at 22, when he published his World War Two-themed book Williwaw. Two years later, in 1948, he published The City and the Pillar, a novel that dealt openly with queerness. The book was denounced as depraved, and Vidal was, for several years, blacklisted by newspapers, including The New York Times. He resorted to publishing mystery novels under the pseudonyms Edgar Box, Katherine Everard, and Cameron Kay, and made money by writing for television and the movies. He was a contract writer at MGM, working on the screenplay for Ben-Hur.

By the end of the 1960s, after a failed run at Congress and publication of three successful novels, including Myra Breckinridge (1968), he was a well-known television pundit, popular for his combative style and humorous put-downs. His infamous August 1968 row over the Vietnam war with the reactionary commentator William F Buckley has racked up more than a million views on YouTube. In it, Vidal described Buckley as “Hitler, without the charm” and then called him a “crypto-Nazi”. “Now listen, you queer,” Buckley snarled. “Stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered.” The pair were later embroiled in a fruitless three-year lawsuit. Well, Vidal did joke that after you turn 50, litigation replaces sex.

Vicious feuds were a feature of his relationship with other writers. He sued (and was countersued by) Truman Capote, after the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s claimed that Vidal had been thrown out of the White House by Bobby Kennedy for being “drunk and obnoxious”. Vidal later told this very newspaper: “Capote I truly loathed. The way you might loathe an animal. A filthy animal that has found its way into the house.”

Although Vidal’s fiction won him admirers – especially for Julian (1964), a vivid and painstakingly researched historical novel about the fourth-century Roman emperor – he was prickly about authors who were feted by critics. In 1996, Vidal wrote a 10,000-word diatribe about Pulitzer Prize winner John Updike for The Times Literary Supplement, claiming the author of the Rabbit series “describes to no purpose”.

He later told an interviewer: “I can’t stand Updike. I’m supposedly jealous; but I out-sell him. He’s just another boring little middle-class boy hustling his way to the top.” Male writers weren’t the only targets of his acerbic humour. When asked to name the three most dispiriting words in the English language, he replied: “Joyce Carol Oates.”

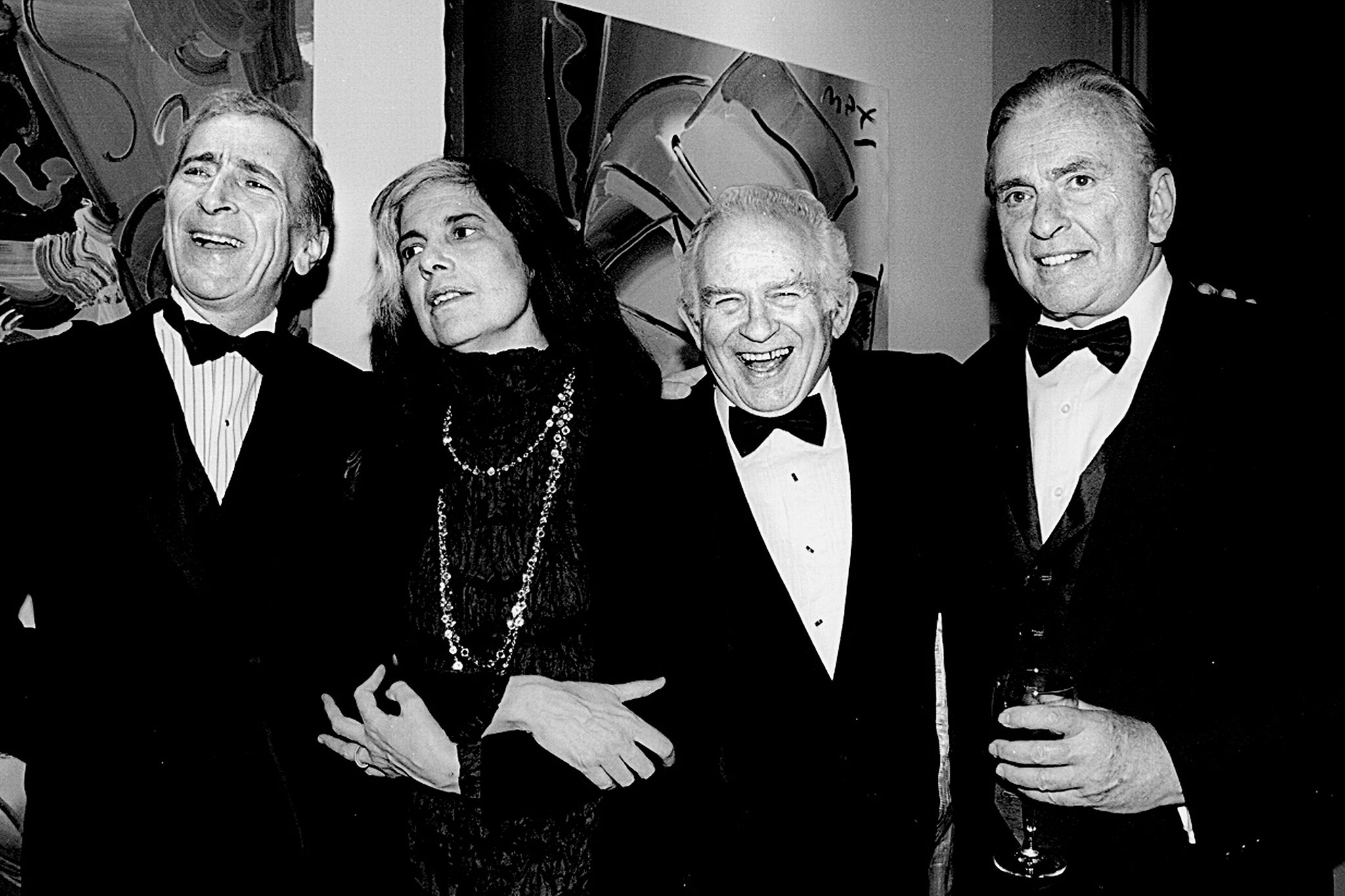

Vidal’s confrontations were not always restricted to word spats. He once wrote a graphic account of a brawl he had with a married merchant marine, whom he had picked up in Seattle. His most physically violent public clashes, though, were with Norman Mailer, author of The Naked and the Dead. In 1971, in the green room before an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, Mailer headbutted Vidal after Vidal compared him to convicted killer Charles Manson. Six years later, at a party in New York, Mailer punched Vidal to the floor, where he wiped a speck of blood from his mouth and said: “Once again words fail Norman Mailer.”

That was the thing about Vidal: he was extremely witty. When Richard Adams, author of Watership Down, called his work “meretricious”, the American instantly retorted, “Really? Well, meretricious to you and a happy new year.” When he was attacked by a right-wing evangelist, Vidal quipped: “I have just been denounced as the Antichrist. I am walking on air. What a promotion!”

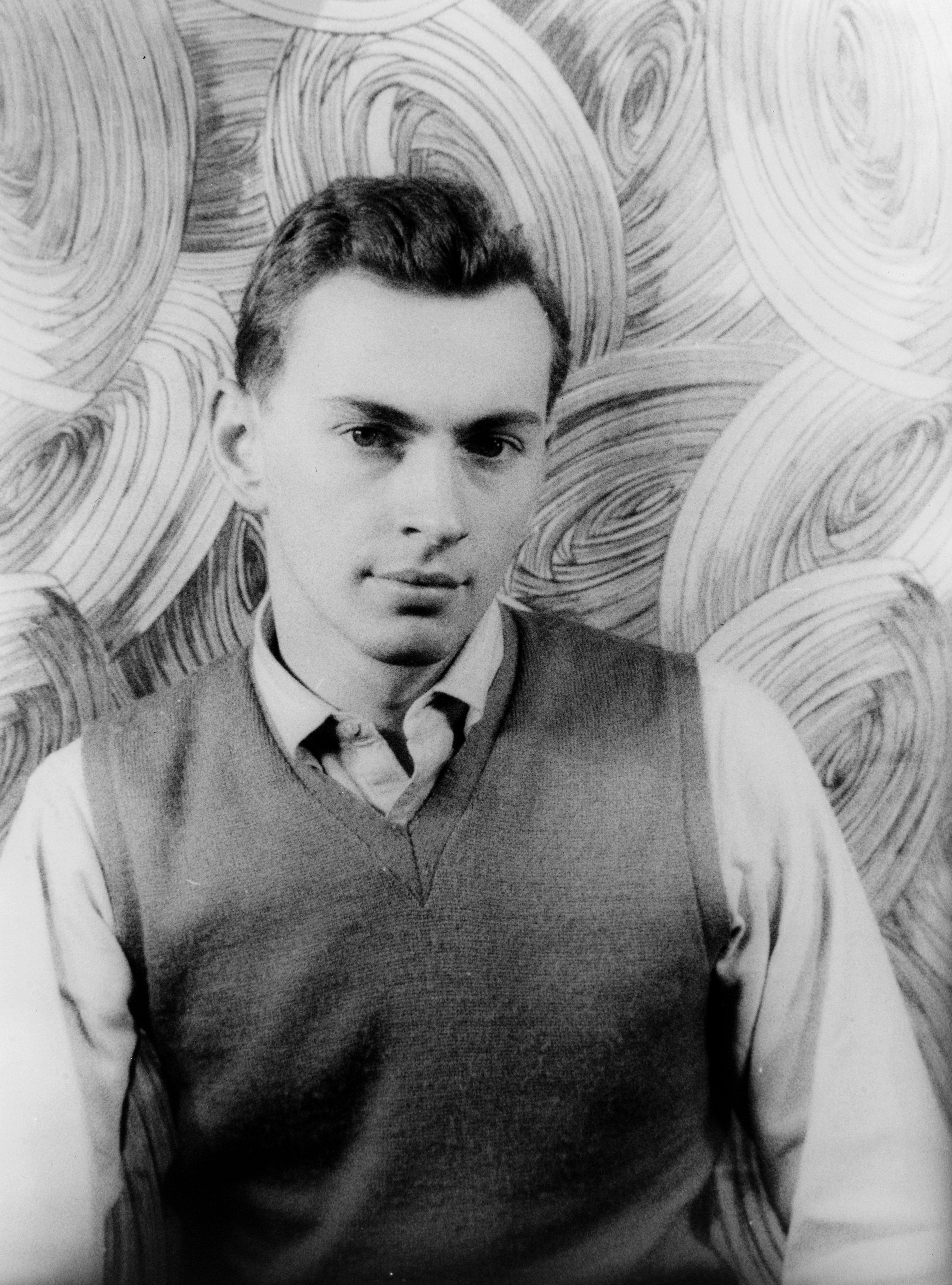

He was close friends with the great and the good, including playwright Tennessee Williams, actor Paul Newman and Princess Margaret. Anaïs Nin described Vidal as “luminous and manly”. Vidal, who was six feet tall, had Ivy League good looks and liked to keep his dark hair immaculately kept. He squinted to avoid wearing glasses as he was concerned about how they made him look. In 1974, a Paris Review interviewer noted that “his teeth are meticulously capped”.

The man who memorably described Ronald Reagan as ‘a triumph of the embalmer’s art’ would have had a field day with Donald Trump

He made no secret of his prodigious love life as a young man, revealing in his memoir Palimpsest that he had had more than 1,000 sexual encounters with men and women by the age of 25. One of his conquests was Jack Kerouac, whom he met in 1949 at the Metropolitan Opera. “As everybody knows, I f***ed Kerouac,” he bragged nonchalantly in a 1994 interview.

Vidal later lived with companion and copywriter Howard Austen for five decades, even though he insisted “love is not my bag”. Possibly, but this was also a man whose final request was to be buried at Rock Creek Cemetery, beside Austen and his own near teenage lover Jimmy Trimble, who had been killed at Iwo Jima in 1945.

But Vidal was much more than a talk-show star and literary gadfly. He deserves respect for his historical fiction. Vidal’s profound sense of America’s past was demonstrated in his Narratives of Empire novels – Washington, D.C. (1967), Burr (1973), 1876 (1976), Lincoln (1984), Empire (1987), Hollywood (1990), and The Golden Age (2000) – which, taken together, offer a coherent view of the nation’s decline. I would also highly recommend Essays, United States 1952-92, a deserved winner of the 1993 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Some books, including his religious satire Live From Golgotha, are perhaps best forgotten.

Vidal detested politicians in general – “they tell lies, even when they don’t have to,” he remarked – and was insightful about the failings of America as it entered what he called “the Dark Ages”. “What we are seeing,” he wrote in 2006, “are the obvious characteristics of the West after the fall of Rome: the triumph of religion over reason; the atrophy of education and critical thinking”. The man who memorably described Ronald Reagan as “a triumph of the embalmer’s art” would have had a field day with Donald Trump.

For all the causticity he reserved for others, Vidal could also turn a cold, analytical eye on his own character. He once said: “I’m exactly as I appear. There is no warm, lovable person inside. Beneath my cold exterior, once you break the ice, you find cold water.” After spending time with Vidal in Italy, writer Erica Jong described Vidal as “a voice for sanity in a mad world” and yet still, came away depressed by her encounter with “the coldest man I’ve ever met and the saddest”.

As he aged, Vidal’s pronouncements grew more and more outlandish. He befriended Timothy McVeigh, the far-right domestic terrorist whose bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995 killed 168 people and injured hundreds more. In an interview with The Independent, he called McVeigh “a noble boy”.

Long-term admirer Christopher Hitchens said that the 9/11 terrorist attack “accentuated a crackpot strain” in the author whose writing had lost much of the sparkle, wit and profundity that had lifted his best work. Hitchens noted that Vidal had also produced “a small anthology of half-argued and half-written shock pieces that either insinuated or asserted that the administration had known in advance of the attacks on New York and Washington and was seeking a pretext to build a long-desired pipeline across Afghanistan”. In an interview with The Independent, Hitchens repeated his attack on Vidal, saying the author “openly says that the Bush administration was ‘probably’ in on the 9/11 attacks, a criminal complicity that would “certainly fit them to a T”. When Vidal learned of Hitchens’s criticism, he denounced him, adding: “What has he ever done?”

Vidal had always been gossipy, sharp-tongued and keen on a cruel quip, but alcohol abuse, the mental and physical effects of ageing and possibly a realisation that his work had fallen off all brought out a mean-spiritedness that was deeply unappealing. In his 2021 memoir Baggage: Tales from a Fully Packed Life, actor Alan Cumming offered a dismal account of his trip to stay with Vidal in Ravello, Italy, shortly after 9/11. Cumming recalled that Vidal was drunk on whisky (he devoured single-malt Macallan), slurred his words and rattled out snide observations. Perhaps most damning of all, Cumming, who compared Vidal’s behaviour to that of “a bitter old queen”, said he found the grand old man of American letters to be “boring”.

Vidal often described himself as being “lucky” and indeed when weighing up his fortunes to his friend and fellow writer Martin Amis, Vidal said simply, “My God, what a lucky life.” That may have been true of most of it, but not of the final years. After turning 80, he was mourning Austen, who died in 2003, and suffering constant problems with his titanium knee. His drinking was out of control and he was plagued by the effects of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (the disturbingly named “wet brain”), including hallucinations, paranoia and loss of bladder control. He reached, in biographer Jay Parini’s words, “a stage in alcoholism when the drinker begins to lose touch with reality”.

His nephew, screenwriter Burr Steers, painted an equally grim picture of Vidal’s “miserable, drawn-out, deranged decline”, with the emaciated author beset by diabetes and congestive heart failure. Vidal believed the CIA had infiltrated his home and, according to Tim Teeman in In Bed With Gore Vidal: Hustlers, Hollywood and the Private World of an American Master, would suddenly shout insults such as, “Your mother was a Polack!”. In 2009, by which time he was in a wheelchair, Vidal complained to an interviewer about America becoming “the Yellow Man’s Burden”, bemoaning a time in the near future when the Chinese “will have us running coolie cars”.

The image of a cantankerous, intolerant and delusional old man is unpleasant. I prefer to think of the dazzling essayist, so capable of provoking both laughter and outrage, and of a public speaker so adroit at lampooning political dishonesty and chicanery.

Before his death, from complications of pneumonia, he bequeathed his $37m fortune and all literary assets to Harvard, a choice two distant relatives failed to overturn in court. Vidal, though, was delighted to leave his estate to a university that was a repository for the Henry James collection, a writer Vidal described as “the master of the novel”. Although Vidal’s fiction never matched the elegance or complexity of James, he did firmly believe that they both shared a love of ambiguity and irony.

Although it is only 13 years since Vidal left what he called “this ark of fools”, he already seems a polymath from a lost age, the sort of acerbic, insightful political commentator missing in a social media age of foghorn popular pundits such as Piers Morgan. But when all is said and done, fame is fleeting; Vidal’s desire to be remembered as the person who wrote the best sentences of his age was always doomed. At Harvard, according to Leslie Morris, the Gore Vidal Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts, the item that attracts the greatest attention is Vidal’s screenplay for the porn film Caligula – which he himself described as “easily one of the worst films ever made”.

Celebrity Traitors is coming this autumn. Here’s all the rumoured names

All the active MCU actor that has not been cast in Avengers: Doomsday

What to read this April, from a very candid Doctor Who biography to five-star fiction

Beatles biographer Ian Leslie on John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s ‘erotic’ bromance

Vanity Fair’s lavish Nineties era is enough to make any journalist today depressed

This book brings the grim horrors of London’s rental market to life