On the Kiwi doctor who lost his life saving the lives of hundreds of people in wartorn Ukraine

Andrew Baghsaw was usually a man of few words, including by text, but in August 2022 when he wrote home, his descriptions of evacuating Ukrainian civilians were longer and more vivid than before, suggesting that his experiences were having a deeper and deeper impression on him.

"Soledar is burning in hell," he wrote. "Every building is damaged. Public services don't exist at all. Volunteers are risking their lives just to bring them basics for life. Many people are too frightened to leave their shelters or don't want to see others risking their lives to help them. Those that do are often in tears. They know they're leaving everything they have behind for a life of refugee status with inadequate housing if any."

He then talked about the toll that Ukraine was taking on his and other volunteers' cars. "And it's not just breakdowns and shelling to which we've lost cars," he wrote. "We lost two to anti-personnel mines. Both drivers were concussed and one ruptured an eardrum. I hit a small one myself, known as a petal mine, but it just blew the tyre. Sounded like a cannon. They are designed to blow people's feet off. Children play with them. At least we know where the minefields are now, which is a plus.

"I've also been shelled close by several times including by cluster munitions," he wrote. These weapons are banned by many countries — but not Russia. "Yesterday I visited a forward Ukrainian army position to consult with them and heavy artillery shells landed a few metres away just a minute or two after I got into their shelter."

In another message he talked about the desperate need he saw in eastern Ukraine. "Bakhmut military hospital, where they took me when my car broke down, is the main hub for casualties in the Donbas. It has no mortuary or flushing toilet."

Australian journalist and volunteer Bryce Wilson, who met Andrew in Soledar in the summer of 2022, remembered the intensity of those months — the cluster munitions, the artillery, the helicopters and the fighter jets. It was noisy and terrifying and relentless in summer before it died down for a while, only to flare up again, even more ferociously, in winter.

Bryce described the action in an Instagram post in August, and talked about the frustrations involved in his work; the sheer difficulty of persuading people to leave. Three people killed by shelling likely included one that he had failed to convince to leave the last time he was there. "I can only speak to my experience, but after coming under close fire from rocket artillery, and then being buzzed by fighter jets as they fired rockets at Russian positions, it was a hectic couple of days." Once they nearly convinced a whole family to go with them, but after packing all the family's stuff into their vehicles, the mother changed her mind and decided to stay — and so all their belongings had to be unpacked again. The family returned to their basement. "Her sons were crying and ready to leave. You tell them they're likely to die by remaining."

Andrew was in the midst of all this, doing the same work alongside Bryce, who had fond memories of him. "Andy was a pretty kooky dude, in a very endearing way," he said. There was shared camaraderie between an Australian and a New Zealander that often came easier than relationships with eastern and central Europeans, who could find it harder to comprehend the dark and self-deprecating Antipodean sense of humour. Bryce thought Andrew was especially witty, in a wry, straight-faced way.

Yet he never really got a clear sense of Andrew's motivations; somehow Andrew seemed to fly under the radar. Volunteering was often heroic — and could look dramatically so in clips edited for maximum impact on Instagram and YouTube. But where others leveraged their heroism and social-media presence towards building up a platform, Andrew "was just there working, day in and day out, for months". Andrew's strongest quality, Bryce thought, was that he was reliable.

There was a system for evacuations. The Kramatorsk volunteers gathered at set assembly points every morning to get their "orders", meaning evacuation requests. They usually worked in teams of two, with one translating and one driving, but sometimes there were more. Each team was given a list of names and addresses, as well as GPS coordinates, and tried to move through the list as swiftly and safely as possible. Bryce confessed that there was often some competitive macho excitement in getting to go to the hottest spots on the list, but Andrew was never desperate to get into "the shit", as soldiers often call the violence and high drama of combat. He was just as happy to be driving, happy to be ferrying people around. He was known to be a safe driver and a good navigator.

Patience was required in their negotiations with local people. An elderly woman, for example, might finally be persuaded to leave her home with a few bags of belongings and possibly a dog or a cat. "They might take random things. Half a bag of sugar and a clock radio." The volunteers needed to have a "holistic" set of skills, according to Bryce. Sometimes they might be talking to people for four or five days before finally getting them out, all with the help of a patient translator. Bryce recalled one particular mission he went on with Andrew in which they were sent to help a single mother who had two traumatised children. Of course the mother was traumatised as well, but she was still unwilling to leave her home. She made it clear that she was waiting for her husband, who used to beat her regularly, to come back from wherever it was he had gone.

It is probably hard for those outside Ukraine to understand why so many refused to be evacuated, even after President Zelenskyy had urged them to. But they had their reasons. Sometimes people didn't leave because they felt that there was nowhere safe to go. There was uncertainty about money, and uncertainty about where they could live and whether they could work. There was a lot of suspicion among those who had barely been out of their town or city before. Other people had warned them that the foreigners were not rescuers at all, but were kidnappers who were trafficking them somewhere for money or even just taking them off to be shot in the woods. And their apartments might be looted while they were away.

Such scepticism is understandable. People were cut off for months from reliable sources of information, or had never had much contact with the wider world. Others were so dazed and traumatised by the noise and terror of the shelling and bombing that they were no longer able to make sensible decisions.

It was difficult work, Bryce said. Aside from the obvious risks of being in a war zone, it was time-consuming and emotionally draining. Ukraine became very personal for Bryce. He wanted to stand by the Ukrainian people, who he felt had given him a lot. They had given him meaning, for one thing, and that was valuable. And while there were plenty of journalists and others drawn to Ukraine by what Bryce called "a vogue topic", he saw that people like Andrew really were there to do good.

Many of the volunteers saw the situation as a struggle between good and evil. It really was that basic; a matter of life and death. On one mission, for example, they got some children out. Passing through the same town again the next day, they saw that the house where the children lived had been blown up. They, and Bryce included Andrew when he said this, "really saved hundreds of people".

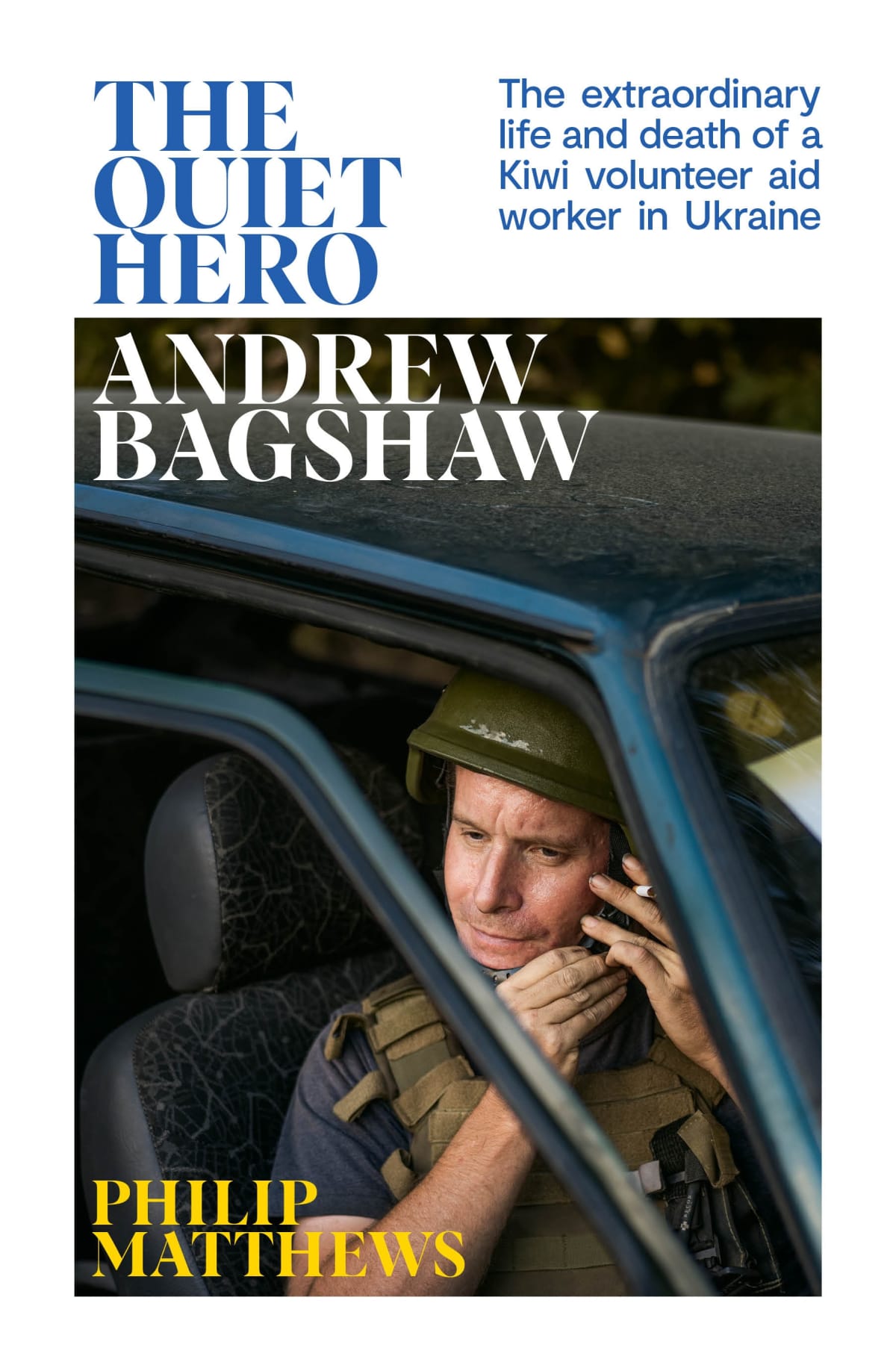

A mildly abbreviated version of a chapter taken with kind permission from The Quiet Hero: The extraordinary life and death of a Kiwi volunteer aid worker in Ukraine by Philip Matthews (Allen & Unwin, $37.99), available in bookstores nationwide.