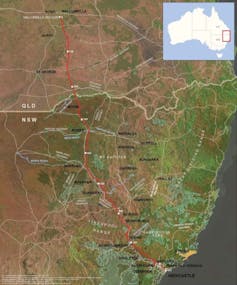

Australian oil and gas giant Santos wants to build an 833-kilometre gas pipeline stretching from southern Queensland to Newcastle in New South Wales. Details released by the company show the project would traverse highly productive farmland, as well as valuable native vegetation.

The pipeline would run underground. Even still, the proposed path is a real risk to threatened species and ecological communities, due to the need to clear a 30m-wide corridor to install the pipeline.

In January, the NSW government granted Santos authority to survey land along the route, with or without permission from landholders. This brings this massive infrastructure project closer to construction.

Many landscapes along the pipeline’s path are already denuded of native vegetation. The threatened ecosystems that remain, including native grasslands, must be protected.

Expanding the gas network across the Liverpool Plains

The proposed pipeline route passes close to Santos’ controversial Narrabri Gas Project. The company claims the pipeline will help alleviate gas shortages along Australia’s east coast.

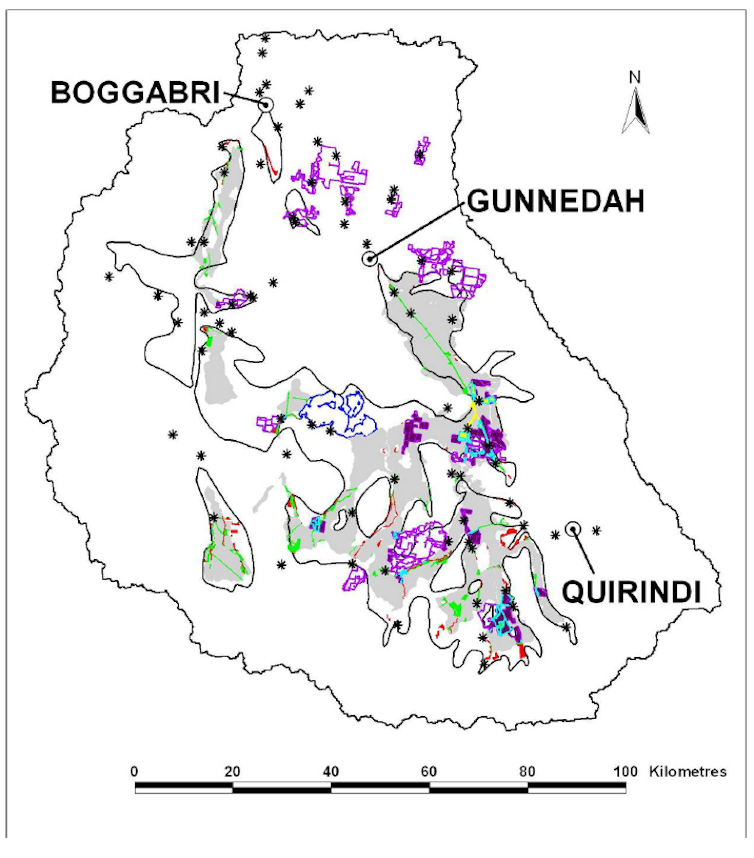

The preferred route for the pipeline runs through the fertile Liverpool Plains, which cover more than 1.2 million hectares of inland northern NSW, near the towns of Gunnedah, Quirindi and Boggabri.

The plains’ deep, alluvial clay soils are renowned for high agricultural productivity. Before European settlement, the plains supported extensive tracts of naturally treeless grasslands, dominated by plains grass, native oatgrass and silky browntop.

Most of the grasslands have been cleared for agriculture. It’s estimated that less than 5% remain.

The grasslands were listed as endangered in 2001 in NSW, and as critically endangered nationally in 2009.

Travelling stock routes and reserves

The proposed pathway for the pipeline includes travelling stock routes and reserves set aside in the late 1800s. Most surviving patches of critically endangered Liverpool Plains grasslands are found along these stock routes.

Yet, Santos has nominated the Pullaming stock route – which runs 25km southeast from near Gunnedah – as a preferred location for the Hunter Gas Pipeline.

This would require clearing a 30-metre wide strip along one side of the road, removing 75ha of these critically endangered grasslands (almost 1% of the estimated 8,000ha remaining).

The extent of the potential damage is detailed in the map and caption below. The green line running southeast from Gunnedah is the narrow strip of native grassland along the Pullaming stock route.

It’s not just the direct clearing that will impact these grasslands. Adjacent stands will suffer from weed invasion.

Stock routes also provide other cultural and ecological benefits, such as:

- providing emergency stock feed

- aiding the conservation of birds, plant communities and koalas

- protecting ecosystems not commonly found in national parks, such as valley flats.

More than ‘minimal impacts’

The NSW state government approved the pipeline in 2009, and this approval was modified in October 2019. It requires the route to, where possible, avoid endangered ecological communities or have minimal impacts. Where damage does occur, this must be offset by biodiversity gains elsewhere.

The proposed clearing of critically endangered grasslands along the Pullaming stock route is hardly a minimal impact.

Biodiversity offsets involve improving biodiversity in one place to compensate for destruction elsewhere. However, offsets are a very controversial tool and are likely to lead to further biodiversity loss if used improperly.

It is much better to avoid the destruction of native vegetation in the first place, especially if that vegetation is critically endangered and essentially irreplaceable. It is not yet known whether Santos plans to use biodiversity offsets for this project.

Read more: A contentious NSW gas project is weeks away from approval. Here are 3 reasons it should be rejected

A project that’s hard to justify

The likely destruction of endangered grasslands occurs along just 25km of the 833km pipeline. Other travelling stock routes and native vegetation will be affected elsewhere along the route, further impacting biodiversity.

Based on the preferred pipeline route through the Liverpool Plains, this massive infrastructure project will either extensively damage highly productive farmland, or harm endangered ecological communities, or both of these.

Given this, it’s difficult to see why the project should be allowed to proceed.

The Conversation approached Santos for comment but did not receive a statement before the publication deadline. However, the company’s web page about the Hunter Gas Pipeline route says Santos intends to consider the environment as well as landholder preferences and “potential constructability issues” before finalising the exact location of the pipeline and the permanent easement.

The company says it is “committed to finding the right balance so that impacts to landholders are minimised, and sensitive areas are protected”. Santos says the path of the pipeline can still be changed, under existing approvals, if certain conditions are met.

Tim Curran receives funding from the New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), Fire and Emergency New Zealand, the Miss E L Hellaby Indigenous Grasslands Research Trust, Marlborough District Council, and the Lincoln University Argyle Fund. Tim is the Immediate Past President of the New Zealand Ecological Society.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.