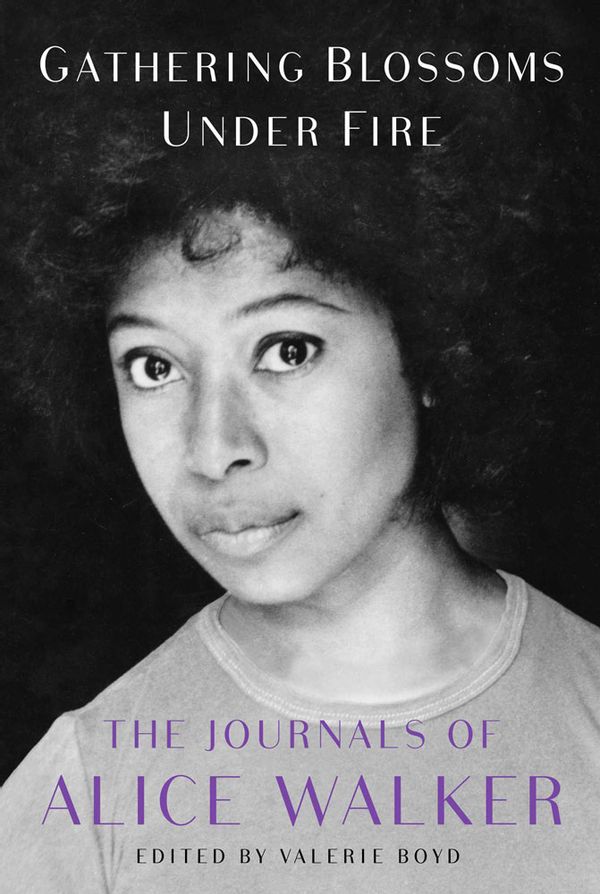

Publication day is here for "Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker," a book that has kept Alice Walker fans waiting for an "intimate glimpse into an important writer's life." Best known for her 1982 novel "The Color Purple," Walker has worked in many genres — poetry, fiction, essays, films, children's books — and influenced public thought as a critic and activist.

At 500 pages, "Gathering Blossoms" includes entries from more than 35 years of Walker's journals, starting with a travel diary given to her in 1962 when she was 18. The book's editor, Valerie Boyd, notes how "the personal, the political, and the spiritual are layered and intertwined" through the ensuing decades.

The journals offer inside details of Walker's work, family, and lovers, including her relationship with songwriter and performer Tracy Chapman, which Walker has been reticent to discuss until now. But readers interested in diaries are also asking: How does her book claim a place in the history of African American women's diaries?

While Walker was keeping these journals, virtually all published diarists were white. Walker discusses Virginia Woolf and Anaïs Nin — even echoes Samuel Pepys' famous words "and so to bed" — but makes no mention of 19th century abolitionist poet Charlotte Forten, nor the other diaries by African American women that slowly began to appear in the 1980s.

Because the spontaneity of a diary brings greater risk to the writer, many more novels and memoirs by African American women have been published than full-length diaries.

Entrenched social obstacles — from the belief that women's diaries lack literary or historical value to the writer's own concerns that material found in her diary might be twisted to reinforce racist or sexist stereotypes — have added up to make the publication of African American women's diaries an unusual occurrence even today. Because the spontaneity of a diary brings greater risk to the writer, many more novels and memoirs by African American women have been published than full-length diaries. Walker's journals represent a new contribution to this rare tradition.

With the success of "The Color Purple" — which won both a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and a National Book Award, after which it became an acclaimed motion picture, a Broadway show and (now in production) a film version of the musical — Walker has achieved fame and wealth that remained an unattainable dream for the earlier African American women whose diaries have been published.

RELATED: "Put the fangs back in feminism": Author Rafia Zakaria on how feminism loses relevance to whiteness

But the record shows they had that dream. Going back to the journal of Charlotte Forten in the 1850s, we find that 21-year-old Charlotte earnestly asks herself, "'What shall I do to be forever known?'" But she quickly adds, as if required to view herself through others' eyes and imagine their judgment, "This is ambition, I know. It is selfish, it is wrong. But oh! How very hard it is to do and feel what is right."

As Charlotte Forten voices her dream followed by self-criticism, she illustrates two key features of the diary form. First, unlike a story or essay, conventionally expected to add up in a way that makes sense, the diary lets fragments float. An entry can pose several statements — comment on the weather, describe an act of lovemaking, note the day's news headlines and confide something that's worrying the writer — without needing to decide between them or draw a conclusion. Thoughts, even ambivalent ones, appear together under the date on which they occurred.

And second, in contrast to the retrospective process of memoir and autobiography, where selected past events culminate in a chosen ending, the diary — even if it's been edited — perennially catches its writer in the moment as she faces daily struggles, experiences shifting emotions and undergoes each transition to a new home, job or relationship, never knowing what comes next.

A literary form that's open to an unknown future and hospitable to internal tensions offers distinct value for African American women.

A literary form that's open to an unknown future and hospitable to internal tensions offers distinct value for African American women, who must battle, even in solitude, against damaging stereotypes and restricted options imposed by the dominant culture. On the pages of her journal where Walker questions a choice after making it, writes admonitory notes to herself as "you," or searches for the right word to describe her sexuality, these sentences are not composed for their effect on readers, even if readers may eventually see this internal dialogue and the contradictions embodied by its writer.

Journalist and activist Ida B. Wells admits in her 1886 diary, "I am an anomaly to my self as well as to others. I do not wish to be married but I do wish for the society of the gentlemen." And editor Gloria Hull believes that 1920s poet Alice Dunbar-Nelson — who, like Alice Walker, describes in her diary passionate attachments to both men and women — may have turned to her diary because "there was not a person in her life with whom she could openly be all of the things that she was."

Keeping a diary, like sewing a quilt, involves stitching together its different parts. Walker's essay "In Search of Our Mother's Gardens" celebrates a revival of arts like quilting, cooking and gardening, all mentioned in her journal entries. These show Walker out there digging and weeding, even as literary success allows her to buy new properties that are increasingly spacious, landscaped and high in price. "My fascination with owning houses," she confides in 1998, "comes from the desire to make where I live beautiful, comfortable; a place where everything works."

But diaries also open a space larger than the individual "room of one's own." Each time writers begin an entry by writing down the date, they anchor that page to a specific moment in history. Diaries offer what "Gathering Blossoms" editor Valerie Boyd calls "an intimate history of our time."

Readers turn to Charlotte Forten and Emilie Davis to learn about African American women's lives during the Civil War. Juanita Harrison chronicles the global adventures of a solitary woman traveler in the 1920s. Walker's journals describe events specific to the late 20th century: civil rights marches, work as an editor with Ms. magazine, a film project that gave visibility to the practice of female genital mutilation in Africa and other parts of the world.

Perhaps the most compelling moments in her journal occur when Walker envisions, begins to draft and greets with joy the success of "The Color Purple."

Perhaps the most compelling moments in her journal occur when Walker envisions, begins to draft and greets with joy the success of "The Color Purple," subsequently becoming deeply involved in its production as a Steven Spielberg film. These accounts are vivid and filled with energy, and — given all the editing needed to produce the book — hopefully they were given in full.

The book's final entry is dated January 8, 2000. For readers wanting to see journal entries written in the 20 years since then, Walker promises in a postscript that "of course, there will be a volume two." However, that promise was made before Valerie Boyd, Walker's trusted editor who worked for over eight years on "Gathering Blossoms," died after a long struggle with cancer. Speaking with a reporter from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Walker has said that she's no longer sure about a second volume.

While waiting to see whether "Gathering Blossoms" will have a sequel, it could be time to check out some of the beautiful earlier examples — like Ida B. Wells' "Memphis Diary," Juanita Harrison's "My Great, Wide, Beautiful World" and Audre Lorde's "Cancer Journals" — that embody the rare tradition of African American women's diaries.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

"Salon Talks" interviews with notable Black women authors on memoir: