Pronoun preferences can elicit wildly different responses from each side of the American culture wars. Yet one category of pronouns is arguably more powerful and influential than those tucked away in email signatures: first-person plural pronouns. Especially when heads of state get their hands on it.

The royal we once signaled monarchs' divine authority: God would send important messages directly to the king, who relayed this heavenly message through his edicts. But it's not just the British royalty who use these politically charged pronouns; the United States was founded on the word we. Few words are as iconically American as the first three words of the Preamble: "We the People." Even when casting off the shackles of the British monarchy, the Founding Fathers couldn't shake the crown's linguistic style.

And few American institutions abuse the word we as much as the American presidency.

The Presidential We

Instead of the royal we, Americans have long endured the presidential we. American history brims with executive overuse of first-person personal pronouns. Whether it's Franklin Delano Roosevelt pitching the New Deal ("The only thing we have to fear is fear itself") or an inexperienced Barack Obama inspiring young voters ("Yes, we can"), presidents frequently invoke plural pronouns to craft a narrative and broaden their appeal.

Abraham Lincoln—who celebrated his election by telling his wife "we are elected"—was one of the first presidents to leverage the presidential we. In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, the word appears more than 12,000 times. Lincoln's "rhetorical substitution of the plural for the singular pronoun" was unprecedented—"as no political leader had done before him"—argued Peter Field, head of the University of Canterbury's School of Humanities, in a 2011 paper for the journal American Nineteenth Century History. Lincoln's preference for the presidential we "enabled his political ascendency in the 1850s and sustained his presidency during the war," claimed Field.

A century and a half later, the presidential we is abundant. Biden, in particular, loves the presidential we. During his 2021 inaugural address, Scranton Joe used 105 first-personal plural pronouns, 89 of which were we. In George Washington, by contrast, used only two in his first inaugural speech.

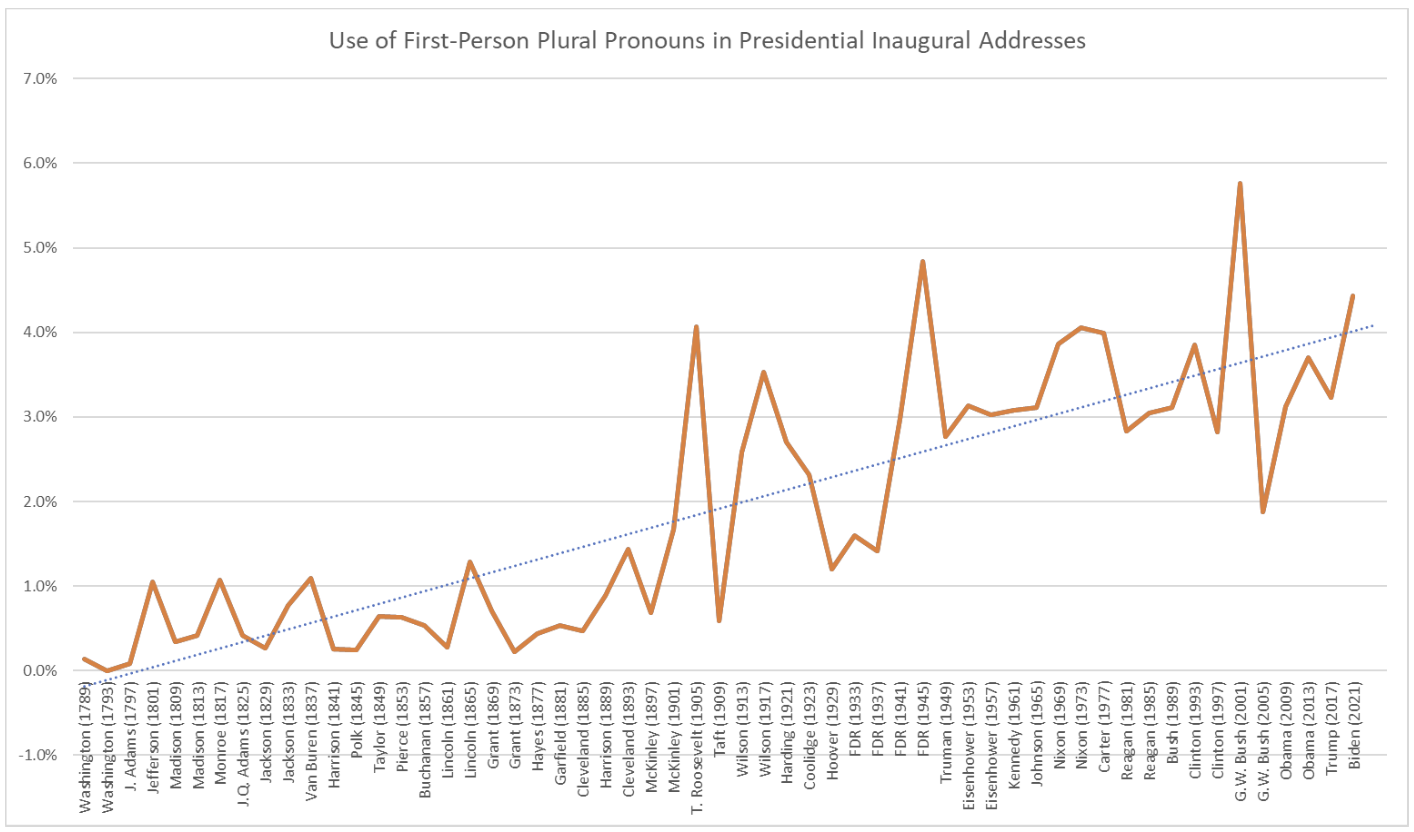

In fact, the presidential we is on the rise. By measuring first-personal plurals as a percentage of the overall word count, the presidential we in inaugural addresses—as expressed with the first-person pronoun percentage (FPPP)—has steadily increased over 57 presidential terms:

Before 1905, the FPPP was, on average, 0.6 percent. In 1905, Theodore Roosevelt more than quadrupled the FPPP to 4.1 percent. Since then, the average has been 3.1 percent. Other peaks include FDR's final address (4.8 percent), both of Nixon's speeches (3.9 percent in 1969 and 4.1 percent in 1973), Bill Clinton's first (3.9 percent), George W. Bush's first (5.8 percent), and Biden's only (4.4 percent).

Research suggests that those who overuse first-person pronouns tend to demonstrate two qualities: They are usually powerful, and they are usually lying.

We've Done the Research—and We Know You're Lying

In a 2013 paper for the Journal of Language and Social Psychology, a research team—James W. Pennebaker, Ewa Kacewicz, Matthew Davis, Moongee Jeon, and Arthur C. Graesser—examined how people use first-person singular and plural pronouns in a variety of settings, from emails between American colleagues to written letters exchanged by Iraqi soldiers.

Their findings reveal that first-person plural pronouns reflect power, authority, and influence. High-status individuals—corporate executives, military brass, or elected officials—favor first-person plurals over their singular counterparts.

The research team concluded, "Because status is conferred collectively by the group, those that appear 'other-oriented'—that is, more cooperative, fair, and collectively focused—attain higher status whereas those who are 'self-oriented' and threaten to take status through force are looked down upon."

In other words, we care about others, and I do not—or so the perception goes. But is that perception accurate?

No, says Pennebaker, a psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of The Secret Life of Pronouns. Pennebaker argues the excessive use of first-person plurals suggests deception.

"A person who's lying tends to use 'we' more or use sentences without a first-person pronoun at all," he says.

Pennebaker has dedicated his professional career to analyzing the words people use to project their innermost thoughts. After years of analysis and experiments, he and a team of graduate students developed a software program called the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). Using it, Pennebaker has analyzed hundreds of thousands of documents to identify speech and writing patterns between groups with varying degrees of truthfulness.

For example, he examined the testimony of convicted individuals exonerated for their crimes versus those who remained imprisoned. Comparatively, the exonerated (i.e., the innocent) favor singular pronouns ("I didn't do it"), while others who were most likely guilty deflect with first-person plural pronouns.

This insight proved helpful in identifying another group with a tenuous grasp of the truth: George W. Bush's administration. Bush and his cronies knowingly lied to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq—and the linguistic signatures of deception were there all along in plain sight.

In 2012, a team led by Jeff Hancock of Cornell University reviewed 532 statements (interviews, briefings, speeches, etc.) by President George W. Bush and senior members of his administration (e.g., Dick Cheney, Colin Powell, Donald Rumsfeld) while they made their case for the invasion of Iraq. With the benefit of hindsight, Hancock's team flagged the administration's false claims, such as the ones involving weapons of mass destruction and Iraq's relationship with Al Qaeda. They then applied the LIWC to these flagged statements, and the same linguistic patterns emerged: Bush and his team hid their deceptive plans for Iraq behind the same deceptive pronouns.

What Can We Do?

Roscoe Conkling, a Civil War–era U.S. senator from New York, once criticized President Rutherford B. Hayes for overusing the presidential we. Conkling famously insisted only three groups of people abuse the pronoun: emperors, editors, and people with tapeworms.

That suggests a solution to this pronoun misuse—the editing part, not the tapeworm. Editors battle ambiguity and cultivate clarity, which entails asking clarifying questions to better understand the writers' intent. Concerned citizens must hone their editing skills, especially during election years. When presidents, lawmakers, and bureaucrats cryptically endorse collective actions and policies, Americans must decrypt by asking clarifying questions.

When in doubt, ask the same question Tonto asked the Lone Ranger, "What do you mean 'we,' Ke-mo sah-bee?"

Whom does the pronoun address? Is it the traditional inclusive version that merges the speaker and at least one other person? Is it an exclusive nosism that pluralizes the speaker while excluding the audience ("don't call us; we'll call you")? Or is it the patronizing brand that places the onus on the audience while absolving the speaker?

These questions will beget more questions. Who genuinely wants to declare war? Who benefits from this multibillion-dollar omnibus bill? Who bears the greater financial burden to subsidize these boondoggles and quagmires?

Unfortunately, the two leading presidential candidates—Donald "We will make America great again" Trump and Kamala "We've been to the border" Harris—both seem poised to carry on the rhetorical tradition of the presidential we.

In other words, we might be royally screwed.

The post The Presidential We appeared first on Reason.com.