On April 4, 2023, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced the indictment of former president and current presidential candidate Donald Trump on 34 felony charges related to alleged crimes involving bookkeeping on a 7-year-old hush money payment to an adult film actress.

Trump is unlikely to wind up in an orange jumpsuit, at least not on this indictment, and probably not before November 2024, in any case. Yet if he does, he would not be the first candidate to run for the White House from the Big House.

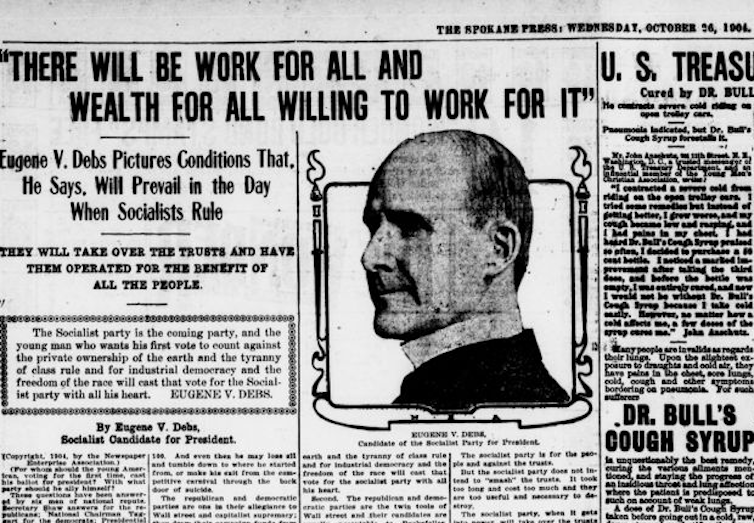

In the election of 1920, Eugene V. Debs, the Socialist Party presidential candidate, polled nearly a million votes without ever hitting the campaign trail.

Debs was behind bars in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, serving a 10-year sentence for sedition. It was a not a bum rap. Debs had defiantly disobeyed a law he deemed unjust, the Sedition Act of 1918.

The act was an anti-free speech measure passed at the behest of President Woodrow Wilson. The law made it illegal for a U.S. citizen to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the United States government” or to discourage compliance with the draft or voluntary enlistment into the military.

By the time he was imprisoned for sedition, Eugene Victor Debs had enjoyed a lifetime of running afoul of government authority. Born in 1855 into bourgeois comfort in Terre Haute, Indiana, he worked as a clerk and a grocer before joining the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen in 1875 and finding his vocation as an advocate for labor.

Representing American socialism

For the next 30 years, Debs was the face of socialism in America. He ran for president four times, in 1900, 1904, 1908 and 1912, garnering around a million votes in the last cycle.

“The Republican, Democratic, and Progressive Parties are but branches of the same capitalistic tree,” he told a cheering mass of people in Madison Square Garden during the 1912 campaign. “They all stand for wage slavery.”

In 1916, he opted to seek a seat in Congress and deferred to socialist journalist Allan L. Benson to head the party’s ticket. Both lost.

In April 1917, when America joined World War I’s bloodbath in Europe, Debs became a fierce opponent of American involvement in what he saw as a death cult orchestrated by rapacious munitions manufacturers. On May 21, 1918, wary of a small but energized and eloquent anti-war movement, Wilson signed the Sedition Act into law.

Debs would not be muzzled. One June 18, 1918, in an address in Canton, Ohio, he declared that American boys were “fit for something better than for cannon fodder.”

In short order, he was arrested and convicted of violating the Sedition Act. At his sentencing, he told the judge he would not retract a word of his speech even if it meant he would spend the rest of his life behind bars. “I ask for no mercy, plead for no immunity,” he declared. After a brief stint in the West Virginia Federal Penitentiary, he was sent to serve out his sentence at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary.

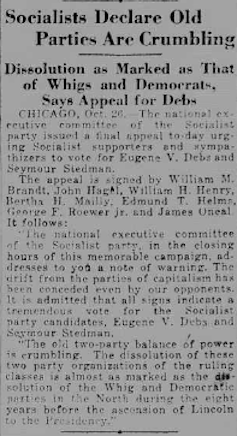

Imprisonment only enhanced Debs’ status with his followers. On May 13, 1920, at its national convention in New York, the Socialist Party unanimously nominated “Convict 2253” as its standard bearer for the presidency. Debs was later given new digits, so the campaign buttons read “For President, Convict No. 9653.”

As Debs’ name was entered into nomination, a wave of emotion swept over the delegates, who cheered for 30 minutes before bursting into a rousing chorus of the “Internationale,” the communist anthem.

A ‘front cell’ campaign

Debs’ opponents both were better funded and enjoyed freedom of movement: They were Warren G. Harding, the GOP junior senator from Ohio, and James M. Cox, governor of Ohio, for the Democrats.

Yet Debs did not let incarceration keep his message from the voters. In a wry response to Harding’s “front porch” campaign style, in which the Republican candidate received visits from the front porch of his home in Marion, Ohio, the Socialist Party announced that its candidate would conduct a “front cell” campaign from Atlanta.

In 1920, broadcast radio was not a factor in electioneering, but another electronic medium was just beginning to be exploited for political messaging. On May 29, 1920, in a carefully choreographed event, newsreel cameras filmed a delegation from the Socialist Party arriving at the Atlanta penitentiary to inform Debs officially of his nomination. The intertitles of the silent screen described “the most unusual scene in the political history of America – Debs, serving a ten-year term for ‘seditious activities,’ accepts Socialist nomination for Presidency.”

After accepting “a floral tribute from Socialist women voters,” the “Moving Picture Weekly” reported, the denim-clad Debs was shown giving “a final affectionate farewell” before heading “back to the prison cell for nine years longer.”

At motion picture theaters across the nation, audiences watched the staged ritual and, depending on their party registration, reacted with cheers or hisses.

The New York Times was aghast that a felon might canvass for votes from the motion picture screen.

“Under the influence of this unreasoning mob psychology, the acknowledged criminal is nightly applauded as loudly as many of the candidates for the Presidency who have won their honorable eminence by great and unflagging service to the American people,” read an editorial from June 12, 1920.

Public opinion turns

On Nov. 2, 1920, when the election results came in, Harding had trounced his Democratic opponent by a record electoral majority, 404 electoral votes to Cox’s 127, with 60.4% of the popular vote to Cox’s 34.1%. Debs was a distant third, but he had won 3.4% of the electorate – 913,693 votes. Debs’ personal best showing was in the presidential election of 1912, with 6% of the vote. To be fair, that was when he was more mobile.

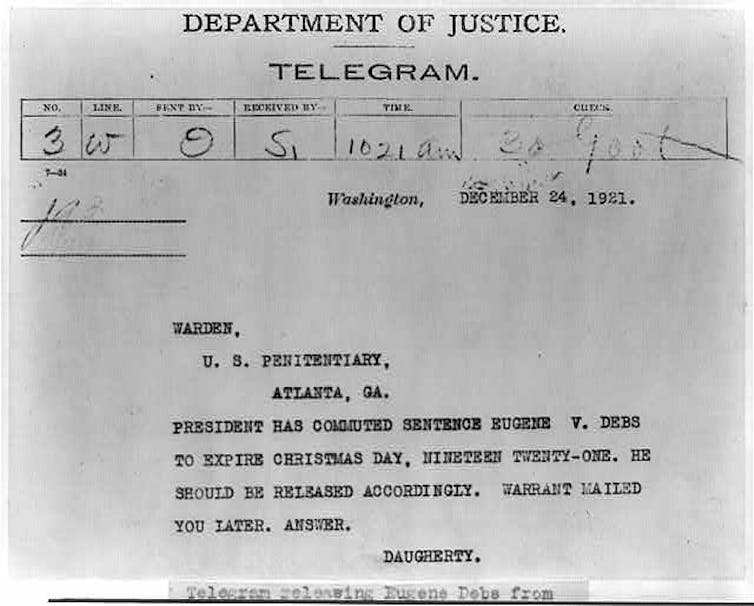

Even with the Great War over and the Sedition Act repealed by a repentant U.S. Congress on Dec. 13, 1920, President Wilson, during his final months in office, steadfastly refused to grant Debs a pardon. But public opinion had turned emphatically in favor of the convict-candidate. President Harding, who took office in March 1921, finally commuted his sentence, effective on Christmas Day, 1921, along with that of 23 other Great War prisoners of conscience convicted under the Sedition Act.

As Debs exited the prison gates, his fellow inmates cheered. He raised his hat in one hand, his cane in the other, and waved back at them. Outside, the newsreel cameras were waiting to greet him.

It was the kind of photo op that Donald Trump might relish.

Thomas Doherty does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.