One freezing evening in early 1993, the first season of the Premier League, a friend and I went to watch Arsenal vs Leeds. We showed up at Highbury stadium without tickets, paid about £5 each, and stood at the Clock End. The small ground was only two-thirds full, with 26,516 spectators. Unfortunately, a large chunk of them were standing in front of us, so I could see little of the muddy field, and nothing of the goal at our end. All four goals were scored there.

Tiny Gordon Strachan was brilliant for Leeds. “Dunno what they feed him on,” said the man next to us, and he shouted at the Arsenal defence: “Go on, tackle him! What are you, the Gordon Strachan Appreciation Society?” Arsenal’s David Hillier, not a crowd favourite, got a booking for his umpteenth clumsy lunge. “Send him off, ref!” shouted an Arsenal fan. “Ban him for life!” advised another. “Or longer if possible!” added a third. Watching the match highlights on YouTube (time travel is now possible), what struck me was that almost every player was white and British, and that the football was dreadful.

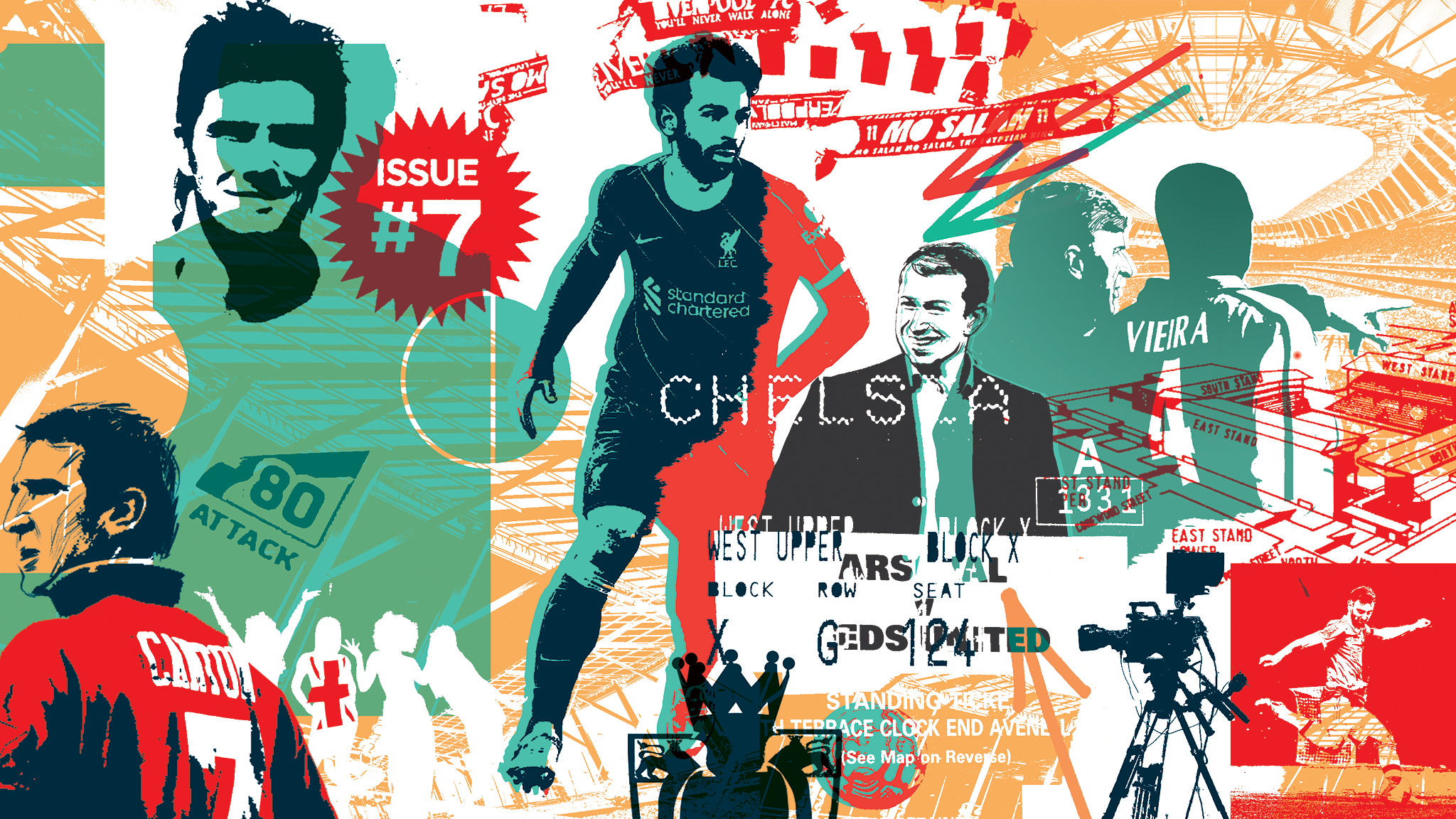

Thirty years ago this week, England’s first-division clubs resigned from the Football League in order to set up the Premier League. Their creation has become the most globally watched league in sporting history. Judging by clubs’ results in European competition, the Premier League overtook Spain as the strongest league in Europe, and therefore the world, in 2017.

Almost every Premier League game this weekend will feature multiple players of Strachan’s quality. All this has happened in a midsized nation that produces few great footballers. The story of the Premier League is an alternative history of modern England. The league has succeeded thanks to English strengths and peculiarities, among them the country’s relationship with money.

English clubs had dominated European competitions in the late 1970s and early 1980s, helped by an excellent generation of Scottish, Welsh and Irish players. But the English game had entered the 1990s reeling from two crowd disasters. Thirty-nine people were crushed to death at the Heysel stadium in Brussels in 1985 as Juventus fans fled from Liverpool supporters. Four years later, another crush at Hillsborough, caused by bad policing on a terrace like a cattle pen, ended up killing 97 people.

Hopes were not high in October 1990, when Greg Dyke, head of ITV Sport, the channel that screened top-division games, hosted a dinner for the chairmen of England’s self-proclaimed “Big Five” clubs. They were scheming to break away from the Football League so they could stop sharing TV rights income with the other 87 clubs. The plan was that ITV would buy the five clubs’ rights directly. The chairmen ended up deciding to create the Premier League. Dyke told me decades later: “Who could have foreseen that we’d end up with English football being largely owned by foreign owners, managed by foreign managers, and disproportionately played by foreign players?”

The Premier League’s early advances were partly accidental, thrust on the backward game by outsiders. A new satellite broadcaster, Rupert Murdoch’s Sky Sports, outbid ITV, buying the league’s TV rights for £60.8mn a season — a scarcely believable bonanza at the time.

Only people who bought satellite dishes could watch the new league. But the government allowed it because post-Thatcher Britain trusted the free market — an essential condition for the Premier League’s success. A more social-democratic Germany has kept a bigger share of its league action on various free channels. Admirable as that is, it has meant that Europe’s biggest football country and economy cannot finance Europe’s best league.

Meanwhile, after Hillsborough, the British government had ordered clubs to renovate their crumbling stadiums and make them all-seater. It was an obvious business idea, but football clubs had always resisted it. Once they were forced to modernise their grounds (and toilets), bingo: more customers came, including even some women and families.

Low, cheap roofs amplified the fans’ singing. The noise urged players into frenzied action — a hallmark of the Premier League

Once English stadiums became safe, they turned out to be perfect venues. Simon Inglis, chronicler of football stadiums, says the genius of the British ground is cheapness. In this historically underfunded working man’s game, writes Inglis: “Form follows whatever the club chairman’s builder pal from the Rotary Club could come up with at a cut-price.”

To save space, stands towered steeply from the field’s edge. There was no athletics track because athletics didn’t pay, so fans were crammed up against the pitch. Low, cheap roofs amplified their singing. The noise urged players into frenzied action — a hallmark of the Premier League.

Swiss architect Jacques Herzog, of Herzog & de Meuron, whose stadiums include Beijing’s Olympic “Bird’s Nest” and Munich’s Allianz Arena, once told me: “The model which somehow started our passion was the classical English stadium. Often the stadium is ugly, like Old Trafford or Liverpool. But they have very interesting details, like gates or tunnels or other features which make it home for the fans. For instance, the tunnel in Liverpool [with the “This is Anfield” sign] where the players become aware that they are about to enter the field is highly architectural.” Herzog loved the cramped intimacy of English grounds: “The Shakespearean theatre — probably it was even a model for the soccer stadium in England.”

Like the groundlings of Shakespeare’s day, English fans consider themselves participants in the show, co-creating it with their cheers and songs. They aren’t fixated on winning. Defeats become fodder for self-mocking humour, as in the comedian Jasper Carrott explaining life as a Birmingham City fan: “You lose some, you draw some.” Manchester City’s supporters, in the bad years when they watched their team playing tiny clubs in lower divisions, would sing, surrealistically: “We’re not really here.”

The great Dutch footballer Johan Cruyff told me in 2000: “If you look at other countries, they have different values: winning is holy. In England, you could say that sport itself is holy.” Since teams in the Premier League are allowed to lose, they dare to play open, attractive football.

The league drew on two other, ostensibly contradictory English assets: tradition and youth culture. The world’s oldest clubs are staffed by young men with attitude and avant-garde haircuts. In September 1992, for instance, 17-year-old David Beckham debuted for 114-year-old Manchester United. As shown by his marriage to Victoria Adams, a singer in the Spice Girls at the time, English football synergises with that other branch of British youth culture, music. The then shrinking port town of Liverpool produced The Beatles and Liverpool Football Club. Manchester City’s fans sing songs adapted from the City-supporting band Oasis.

The one thing English football was short of at the start of the 1990s was good footballers and managers. French writer Philippe Auclair categorises early Premier League players as “hard-tackling box-to-box one-footed midfielders” and giant centre-halves and centre-forwards with heavy touches. The league needed to import quality. Of the hundreds of foreigners who arrived from 1992, three did most to transform the English game: Eric Cantona, Arsène Wenger and Roman Abramovich.

The Frenchman Cantona landed at Leeds in January 1992 as a glorious failure. At 25, he had already played for six clubs, and had even briefly retired from football, after walking up to each member of the French league’s disciplinary committee and repeating the word “idiot”. He collected red cards. Yet the Premier League needed him.

The young Marlon Brando in raised shirt collar was a visual shock in shabby, recession-hit, pasty-faced early-1990s England. Cantona always seemed to know where everyone on the pitch was, could position himself almost unmarked “between the lines”, and passed with perfect speed and spin. Back then, there wasn’t another player like him in the country. Three months after his arrival, Leeds sealed the title. But such was British mistrust of what was then called “continental flair” that the club soon sold him to Manchester United for a derisory £1mn. When United manager Alex Ferguson told his assistant, Bryan Kidd, the fee, Kidd gasped: “Has he lost a leg or something?”

As a self-proclaimed “artist”, Cantona saw his job as performing to a crowd. He had found small French crowds cold and critical. But English fans responded to him.

Ferguson knew that United — without a league title since 1967 — needed to abandon primitive, long-ball “British” football. Cantona showed him how. In 1993 the Frenchman led United to the Premier League’s inaugural title. He ended up a role model for the entire league.

In 1996, Cantona’s compatriot, Wenger, became manager of Arsenal. “I felt like I was opening the door to the rest of the world,” Wenger said later. He brought knowledge that nobody in insular England at the time possessed. For instance, Michael Cox in The Mixer describes Arsenal’s pre-Wenger diet:

They’d enjoy a full English breakfast before training, and their pre-match options included fish and chips, steak, scrambled eggs and beans on toast. Post-match, things became even worse: on the long coach journey back from Newcastle, for example, some players held an eating competition, with no one capable of matching the impressive nine dinners consumed by centre-back Steve Bould.

Wenger got Arsenal’s players eating fish and steamed veg. A ceaseless pioneer, he encouraged the use of supplements such as creatine; he used statistics to analyse players’ performance; and he knew foreign transfer markets. It didn’t take mystical insight to perceive the brilliance of Milan’s reserve Patrick Vieira and Juventus’s reserve Thierry Henry — the Highbury crowd saw it inside 45 minutes on Vieira’s debut against Sheffield Wednesday — but hardly any other manager in England seemed to have heard of the men. English clubs of the day rarely scouted abroad.

Soon most hired their own foreign managers. (To this day, no English manager has won the Premier League.) But, crucially, for the success of the reality TV show that the league became, they communicated in the global language. Footballers in England mostly keep silent because the tabloids twist their words into scandalous front pages, so the show’s main characters are the managers. The beefs between men such as Wenger, José Mourinho and Pep Guardiola generated worldwide daily interest. It wouldn’t work if they were speaking German.

From 2003, club owners internationalised too. When the Russian oligarch Abramovich decided to buy himself a football club, he considered Spain and Italy. But ownership there seemed complicated. In Italy, many families who owned clubs had been doing business together for generations. In Spain, fans themselves owned the biggest clubs. Abramovich ended up club-hunting in London. Having been wrongly informed that Arsenal wasn’t for sale, he trekked into the north London suburbs to inspect Spurs, but found Tottenham High Road “worse than Omsk”.

Chelsea’s stadium was handily located near Knightsbridge. He bought the club from Ken Bates in 2003, sealing the deal over a bottle of Evian water in the Dorchester Hotel. That started a new era in the Premier League: foreigners buying and funding ancient English clubs.

Some of these fortunes were murkily begotten. When Vincent Kompany signed for Manchester City in 2008, he was told that his meet-and-greet with the club’s then owner, former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, had been cancelled because Thaksin needed to go into hiding after a spot of bother. Still, not to worry. Keith Harris, the pink-faced investment banker, always had a queue of foreigners ringing his phone asking if there were any English clubs going spare. Even Myanmar’s military junta considered buying Manchester United.

The Premier League benefited from the modern English custom of welcoming money of almost any provenance. If the league is an overpriced, foreign-owned, foreign-staffed bazaar, well, so is much of the UK economy. The distrust of international capital so widespread in France or Germany remains weak in England. When the Saudi regime bought Newcastle last year, fans celebrated in mock-Arab headdresses. Free-spending foreign owners have allowed multiple teams to challenge for the title, avoiding the tedium of the German, Italian and French leagues, where a single club established a monopoly for long periods.

But the conversion of English top-flight football into a globalised plutocracy inevitably causes disquiet. There used to be a popular theory that England’s national team failed because the Premier League had too few English players. Here is England’s midfielder Steven Gerrard speaking just before the team failed to qualify for Euro 2008: “I think there is a risk of too many foreign players coming over, which would affect our national team eventually — if it is not doing it now.”

The 2007-08 Premier League season had kicked off with Englishmen making up 37 per cent of starting line-ups. Last season, they accounted for 38 per cent of playing time. The question is: is 37-38 per cent a little or a lot? It equates to more than 70 Englishmen per match day — more than any other nationality in what’s now the world’s best league. The very successful Croatians, Belgians or Portuguese dream of accounting for 37-38 per cent of minutes in any big league.

English internationals learn best practice from competing against foreign stars every week. Their clubs learn, too. The Premier League’s youth academies have been remodelled, often under foreign supervision, and nowadays mass-produce continental-style passing footballers such as Phil Foden, Bukayo Saka and Mason Mount.

Indeed, since the Premier League went international in about the mid-1990s, England’s performances have improved. In the era of a British league, from 1968 through 1992, England reached the quarter-finals of major tournaments four times in 13 attempts.

By contrast, in the “international” period from 1998 to 2018, it reached five quarter-finals in 11 attempts. (I am excluding the three tournaments in which England had home advantage.) Match by match, the top four postwar England managers with the highest win percentage features all three post-2008 incumbents, Fabio Capello, Roy Hodgson and Gareth Southgate, alongside Alf Ramsey, world champion in 1966. The Premier League’s internationalism seems to have benefited the national team. After England’s successful tournaments in 2018 and 2021, anxiety about foreign players dissipated.

But the biggest source of angst around the league has always been money. As early as 1995, Labour leader Tony Blair told a dinner of players and managers at London’s Savoy hotel that the newly flush game risked being “tainted by greed”. He questioned whether any footballer was worth the £7mn recently paid by Manchester United to Newcastle for Andy Cole. He bemoaned rising ticket prices.

Those anxieties persist today, when transfer fees can reach £100mn and the cheapest Arsenal season ticket costs £891. The Premier League’s bottom club receives more TV income than every club in continental Europe except Real Madrid, Atlético Madrid and Barcelona. The annual TV revenues of English top-division clubs rose from £11mn in 1991-92 to £2.5bn last season — a hundredfold rise in real terms. Imagine how much a person might change if their income jumped one hundredfold. Critics warn that English football has lost its identity, or perhaps its soul. In the daily football conversation, the Premier League’s “bubble” is always about to burst.

Yet fans from Tahiti to Burnley seem oddly undeterred. All 20 clubs in the Premier League in 2018-19 averaged more spectators than in 1992-93, calculates sports economist Stefan Szymanski, my co-author of Soccernomics. Of the 78 clubs present in the four top divisions in both seasons, 64 had higher attendance. The Premier League’s rising tide lifted almost all boats.

Occasionally a small club folds under financial problems but is swiftly refounded again and soldiers on, as did Bury and Macclesfield recently. Almost every English club that existed a century ago survives today.

It’s true that rising ticket prices — the average cost is now £32 a match, according to the Premier League’s own figures — exclude many poorer fans. Clubs ought to follow theatres in reserving discounted tickets for the unemployed, disabled people and NHS staff. However, before the Premier League, English football operated a different sort of exclusion: scanning the photos of the crowds of 1992, you wonder: where are the women and black and brown people?

Despite today’s ticket prices, all 60,000 seats in Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium are full whenever Covid restrictions allow. If an Arsenal fan from 1992 or even 1922 were to return for Saturday’s match against Brentford, they would find most things familiar: the game, the club colours, the fans’ attachment, the weekly ritual. Only the football is unrecognisably better.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022