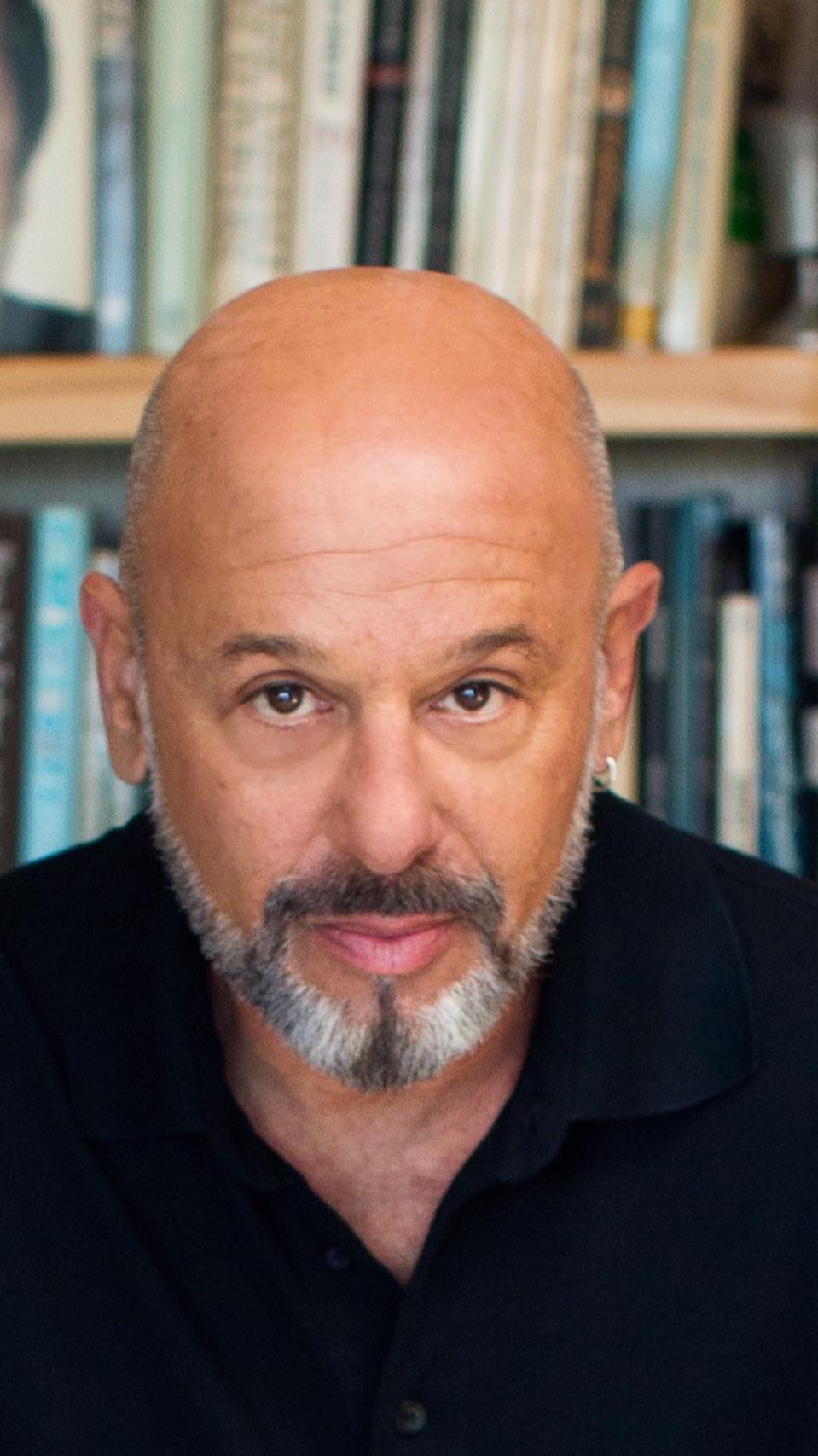

Legendary magazine journalist Mike Sager has so far lived a life most people can only dream of. Some of that is detailed in his latest release, The Pope of Pot, which is a collection of stories and essay’s from the writer’s travails in and around the weed world.

A best-selling author and award-winning reporter and a former Washington Post staff writer and contributing editor to Rolling Stone, he has written for Esquire for more than thirty years. Sager is the author or editor of more than a dozen books, including anthologies, novels, a biography and textbooks. In 2010 he won the National Magazine Award for profile writing. A number of his stories have inspired films and documentaries.

Sager is the editor and publisher of The Sager Group, a La Jolla, Calif.-based independent press that published The Pope of Pot. On 4/20, the day of the book’s release, I sat down with him to ask a few questions.

Jackie Bryant: Okay, I have to know. Who is the Pope of Pot?

Mike Sager: The Pope of Pot founded the nation’s first marijuana delivery service in New York City in 1979. All you had to do was call 777-Cash, give a location and a description of yourself, and then a bicycle messenger would show up within 30 minutes. The son of a Jewish factory owner from New Jersey, like many “hippies” of the day, he found himself in Amsterdam in the 1970s, where learned the weed trade selling out of a series of house boats. His distinction: he sold flower instead of hashish, which was the most commonly available cannabis product in Europe in those days.

His real name was Michael Cesar. I spent about four or five months, on and off, hanging out with him and his crew in 1990 and 1991, but we were friends till the end of his life, mostly by phone. During this period I often stayed in the Hotel Chelsea, part residence, part hotel, a brick and iron monolith that was an extension of the eclectic downtown-facing scene. Besides the profusion of art inside—the owners had for years taken paintings and other works in trade for rent for starving artists— the Chelsea was galvanized in New York lore when Nancy Spungen, the girlfriend of Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols, was found stabbed to death in 1978.

The Pope was a singular personality, a madcap genius who called everyone toots, a Don Quijote kind of guy who saw things not necessarily as they were, but instead how he felt they should be in his own vision of a rainbow colored world, where even his notes to himself and things to do were written in different colored magic markers. (Interestingly, the Hotel Chelsea boasted a Mexican lobster restaurant called El Quijote, where the Pope and I liked to dine on my Rolling Stone expense account. Still there.) A flamboyant gay man and cockeyed optimist, Mickey (as he was called by myself and anyone else who was fond of him, for how could you not be, so pure was his idealistic idiocy, so big was his smile full of yellowed teeth, ss . . . well, he was just kinda cute and cuddly in his own grizzled way) was fiercely unafraid to put his body on the line for the things he believed—and still have a good time doing it. Long before marijuana was legal, he pissed off the New York City cops and politicos with his blatant street protests and public sales of marijuana. At special events, like the annual Halloween Parade in the West Village, Mickey would always be there, riding a float and handing out free “sacrament.” He was also notorious for collecting used syringes from the ground in public parks, like Tompkins Square, in New York City. Though his intention was public safety and awareness of addiction issues, when he tried to turn over buckets-full of used needles to the police, he was arrested for possession of drug paraphernalia.

For all public appearances, Mickey wore his papal miter—a tall, white number with a peaked, Pope Francis-style crown, and a nine-inch marijuana leaf pasted on the front. A lace, polka-dot ribbon tied in a bow under his neck to hold it in place. His “Church of Realized Fantasies” was based in a storefront in the meat packing district, a former comic book store. It was always crowded, if not always heated. Various delivery people and hangers on were allowed to crash; Mickey fed everyone and gave out free weed. He called marijuana “the sacrament” and considered it a holy and healing plant. He even provided his crew of bicycle messengers with a dental plan. His platform was that legalizing marijuana was a right and sane thing to do. To him, it made no sense other wise. It was his job to embody this sentiment, which we now take for granted—on demand weed products in much of the country.

Then one day in 1990, radio’s budding “King of All Media,” Howard Stern, got wind of the Pope’s operation. He called the number, 1-800-WANT-POT. And what do you know: the Mickey the Pope answered. As always he was candid. The live broadcast was being heard by 2 million listeners in three Eastern cities. New York’s police and district attorney could no longer ignore him.

The Pope eventually went to jail on possession and distribution charges, a fifteen-year sentence. I kept in touch via collect phone calls. Never a well man, while inside the Pope complained for months of pain and bloody urine before he was allowed to see a doctor. When he did, he was diagnosed with liver cancer and freed from prison. He died a few months later, in February, 1995. He lived long enough to witness his own wake, a party arranged by his own hand. I was happy to be there. He was such a sweetie. And yet so tough.

Mickey is memorialized as a character in my first novel, Deviant Behavior. I wonder what he would say if he knew that New York has now legalized weed, and that weed delivery is common all over the country. Like another important activist I was lucky to know, Mitch Snyder, who advocated for the Unhoused in the early days of that movement in Washington, DC—holding then-President Ronald Reagan a veritable hostage with his hunger strikes that had him dangling near death—the Pope was someone who, in Snyder’s words, “made of his body a living sign.” Mickey put his life on the line for what he believed.

Back then, of course, people thought he was off his nut.

This story, along with a photograph by Mary Ellen Mark, is his legacy.

JB: What turned you on to pot as a subject? How has that changed since legalization became a thing?

MS: I became a cops reporter at the Washington Post in 1979. I’d been a pot smoker since age 12. I ended up covering the War on Drugs in the mid 1980s thru 1992 for Rolling Stone. I think what happened is when I got to the Post, I couldn’t compete with all the Ivy League talent in more conventional literary fields, but I had street knowledge. If you understand you don’t sensationalize. I think I was able to write about drugs with a more knowledgeable eye. I knew what to ask. When crack first surfaced, I lived with a notorious Mexican American gang in Venice, CA, the V-13. Later, I went to Hawaii to report on smokable meth; I ended up as the sole expert witness from the field at a Congressional sub-committee hearing on Capitol Hill. Likewise I’ve written about hip heroin users in 90s Manhattan, and Oxy-addicted soldiers after Afghanistan. It somehow became my milieu. I think one of my charges to myself in my career has been… start with shit that is fascinating and has action. The drug world was a place I landed and always felt a comfort level. We’ll leave the discussions of Rick James and freebase for another day.

My first rule of reporting. Thou shalt not bore. Drugs ain’t never boring. Except when you’re hopelessly addicted. And then it’s just the same old thing. So that’s part of it to…learning about how to navigate without getting your ass hooked.

JB: What's the deal with your press? It sounds like it's named after you.

Years ago, I was spending time with Ice Cube after he’d just quit NWA. We were in NY and he was working on his first album, Amerikkka’s Most Wanted. One day we got into a conversation about his ambitions beyond rap, his philosophy of business. Bastardizing Karl Marx, Cube spoke of harnessing the means of production in order to realize his own creative ambitions. It always stuck with me. Later, when the magazine industry that I served so well for 35 years or so began to falter, I decided it might not be such a bad idea to harness the means of production myself.

The Sager Group? Back in the day that’s how I thought of my freelance career. It was dependent on the many faces of Mike. I was reporter, writer, accountant, salesman. It took all those guys to be a freelancer. Over the years, as a teacher and a mentor, the group has kind of grown in my mind. When it came time to start a boutique book publisher/content brand, there was really no other name for me to consider. The logo was first drawn by me loosely but executed by my friend Bruce Kluger, who I’ve known since fourth grade and still is one hell of a multi-talented guy.

JB: After the title character, who are some other interesting personalities that appear in the book?

MS: In “Dab Artists” we meet the artesian crafters who occupied the outlaw edge of the vaping boom in the early days of legal weed. Cool but nerdy, deliberately unkempt, these self-taught Heisenbergs of hash oil gathered for the Secret Cup Finals in Las Vegas. It took me 9 months to gain acceptance and be invited.

In “The Pot Doctor Will See You Now,” we meet Don Davidson, MD, a pioneer of online medical marijuana recommendations. Over several years, Dr. D. and his crew of doctors issued hundreds of thousands of weed licenses. A long and jangled day with the hardest working doctor in the marijuana business. Dr. D. went on to be one of the first cannabis entrepreneurs; my content brand designed all his THC and later, after he lost his fortune to a fly-by-night venture capital operation, his CBD products.

JB: Since he's in the book, I feel like this question is fair game. What was your relationship with Hunter S. Thompson?

MS: “Meeting the Ghost of Christmas Future,” comprises the last section of the book. It’s based on my time when Rolling Stone sent me to Woody Creek, CO, to aid my RS colleague. Busted for possession of illegal drugs, he was facing a fifty-year prison sentence. I spent three weeks basically working as his assistant and ghost writer when he was too tied up with trying to stay out of jail. I would say our time together taught one of us some lessons to last a lifetime.

After spending time with Hunter, and his case was over, he came to New York on assignment for Esquire. As it happened, I was in New York at the same time, working on my Pope of Pot story. Late one night, the Esquire editor assigned to squire HST around town, David Hirshey, tracked me down at the Hotel Chelsea. Hunter was having a crisis! He’d lost his ball of hash!

I hung up the phone and called the world’s first pot delivery service owner, Mickey the Pope. HST had weed in a half hour. And I felt like the coolest guy in the world. I’d end up working for Esquire for over 30 years, where I am still an Contributing Editor. Hirshey is still a good friend. And Hunter? Before he died, he gave me a blurb for my first book, Scary Monsters and Super Freaks. From what I can tell, it is the only blurb he ever gave a fellow writer.

He will always be fondly missed.

JB: What's the most fun part of writing about weed?

MS: Fucking with the man. Weed was always about fucking with the man. Now, it’s all commercial, but in a way, it’s a club you belong to. Read my opening piece, “When Should a Man Stop Smoking Weed?” In it I look back on a half-century of pot smoking and reporting, starting on a humid night in summer at age 12.

For me, marijuana has served as a great equalizer, a frequent teacher, and a pleasant companion, leading me places I would never have otherwise gone. What’s not to like.

JB: Anything we missed?

MS: I’ve a dozen books of stories, including one that became Boogie Nights. Check me out at MikeSager.com.