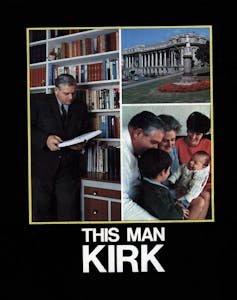

The 1970s may have been a time of flared jeans, paisley shirts and long hair. But the decade was also a time of resistance to such outward signs of modernity and progress. And very briefly, it was also the time of Norman Kirk, who as Labour prime minister between 1972 and 1974 managed to straddle those two New Zealands.

Denis Welch’s We Need To Talk About Norman: New Zealand’s Lost Leader touches on the social mores of that period, but dives deep into Kirk’s significance, now and still. Strictly speaking, the book is neither a biography nor an academic study of political leadership (although it contains healthy servings of both).

It is something else: a meditation on both the state we are in as a nation, and on the other, better place we might be in had Kirk’s story had a different ending. In short, for Welch, Kirk is not the only thing we have lost. Since his death, something deeper, more fundamental has also gone missing from our polity.

Review: We Need To Talk About Norman: New Zealand’s Lost Leader – Denis Welch (Quentin Wilson Publishing)

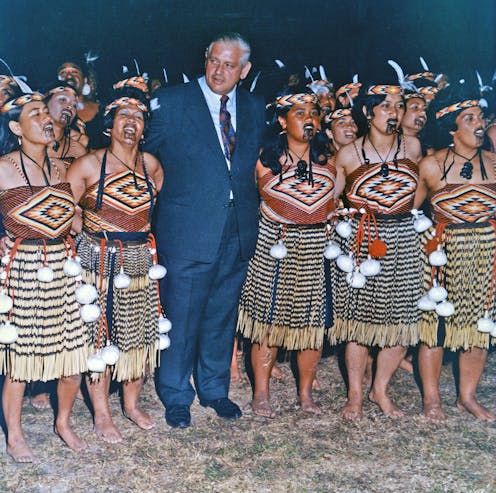

Norman Eric Kirk provides the (capacious) frame through which Welch explores these issues. Some of what is seen is familiar: here is “Big Norm” as the internationalist, cancelling a proposed Springbok rugby tour and driving the first (and to date only) “state-sponsored physical anti-nuclear protest” when the frigates Otago and Canterbury sailed to Mururoa in 1973.

Welch connects Kirk’s politics around nuclear weapons to the fact that his father had been a conscientious objector in the first world war. And here he is as visionary – the first prime minister with a Pacific sensibility and an independent foreign policy, in which Aotearoa New Zealand was no longer “an island off the coast of western Europe”.

To support and enable

But some of what Welch has to tell us will be new.

Kirk’s skill with a sewing needle, for instance, is probably not widely known. (Tangentially, it was a surprise to be reminded that long before he became a standard bearer for the sorts of economic and political policies that Kirk detested, Roger Douglas was the architect of a short-lived superannuation scheme that looked quite a bit like Michael Cullen’s 2001 NZ Super Fund.)

Kirk does not get a free pass. His belief that “We came to nationhood with no legacy of bitterness” would not pass muster today, even if it was orthodox thinking then. And Welch also addresses Kirk’s social conservatism (including his lack of support for homosexual law reform) and the fact the dawn raids began on his watch.

The emphasis, however, is very much on Kirk’s practice of political leadership (compassionate, humane) and views on the purposes of the state (to support and enable, rather than to punish and prevent). Not for Kirk – or Welch – some arid conception of the human condition as one of self-absorbed utility maximisation.

Rather, what animates both the politician and the author is a vision of people as relational, connected beings who want “someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work and something to hope for” – and who need a state for which those things are also the priority.

It is possible, of course, to overdo the agency of leaders, and Welch also acknowledges that an overweening focus on the captain of the team can blind us to deeper, more consequential forces: the broader political culture, for instance, and the wider national and international political economy.

Eventually, the rest of us will leave political leaders behind when the limits of their influence become clear. The vision thing may be important, but there is political blowback when we sense what is required to achieve that vision is beyond any one leader’s control.

Welch’s characterisation of Kirk as a lost leader needs to be seen in this context too; in his failure to prevent the neoliberal revolution from happening.

From Kirk to Ardern

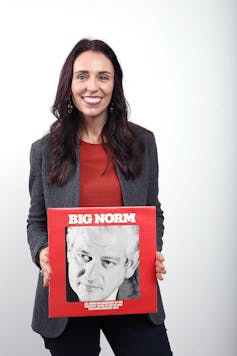

Kirk is not the only lost leader in this book, not the only prime minister you sense Welch thinks we need to talk about. Throughout, Jacinda Ardern provides a constant counterpoint to Kirk.

Welch doesn’t really linger on Lange, Clark and the other Labour leaders – he positions Ardern as Kirk’s true successor on the left. Kirk “cuts a swathe” internationally; so did Ardern. And her “kindness and compassion chime with [Kirk’s] view that ‘Sentiment is the most effective political base’”.

While Ardern may not be lost in all of the ways Kirk is (most obviously, she remains very much alive), the sense that she, too, brought a compassionate moral clarity to the top job, and an understanding of a more balanced relationship between the private and public spheres, is central to Welch’s case.

So is the sense of promise unfulfilled, undone by a domestic political culture in which anything resembling soaring political rhetoric “embarrasses the hell out of us”, and a neoliberal orthodoxy (which Kirk did not have to face) that is decidedly hostile to that form of politics.

The larger narrative arc is the sense of what has been lost – not just leaders but other more significant things – and what might yet be gained.

Kirk’s position that “the role of the welfare state is to set people free” stands in stark contrast with today’s mantra that income support is likely to trap you in an endless cycle of “dependency”.

The sense of service that animated Kirk’s and Ardern’s approach to politics has also fallen from fashion. For Welch, the moral compass of politics – at the level of individual politicians and the arrangement of our institutions – is awry.

Read more: Learning to live with the 'messy, complicated history' of how Aotearoa New Zealand was colonised

The public good

Nonetheless, the book is fundamentally forward looking. Norman Kirk died at the age of 51, his heart – never his strongest point – eventually giving out following surgery to remove varicose veins.

However, Kirk’s work continues. Through Welch’s book, the “lost leader” speaks to us from across half a century, reminding us that there are other ways of thinking about the public good that governments can do, and that politics can be animated by something higher than narrow self-interest and disdain for others.

Politics can have “wide purposes” (an observation the great jurist Owen Woodhouse once made of Kirk’s leadership) rather than the constrained ones we have become accustomed to. Welch is keen to remind us that few things are ever immutable or inevitable, and that politics is not among them.

But Welch is also asking something of us. Three months out from a general election, he’s asking us to consider what sort of country we want to live in. What sort of people we are. What sort of future we want, for ourselves and those who come after us.

He’s asking us not only to talk about Norman, but also to listen to what he might still have to offer. Welch is asking us to consider whether or not Labour’s lost leader(s) might yet help us find a better future. We’ll get to decide that ourselves on October 14.

Richard Shaw does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.