In the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto, photography is a type of embalmment, a tactic of preservation, and an instrument of experimentation.

Born in 1948, Japanese artist Sugimoto works with photography, site-specific sculpture and architecture. Time Machine at the Museum of Contemporary Art surveys over five decades of his work. The exhibition highlights Sugimoto’s conceptual approach to images and his continual investigation of the photographic form.

Sugimoto’s photographs reveal his reverence for technique. They are primarily in black and white, and often made with an analogue large-format camera. These are images made with intent; carefully planned, and often slowly executed.

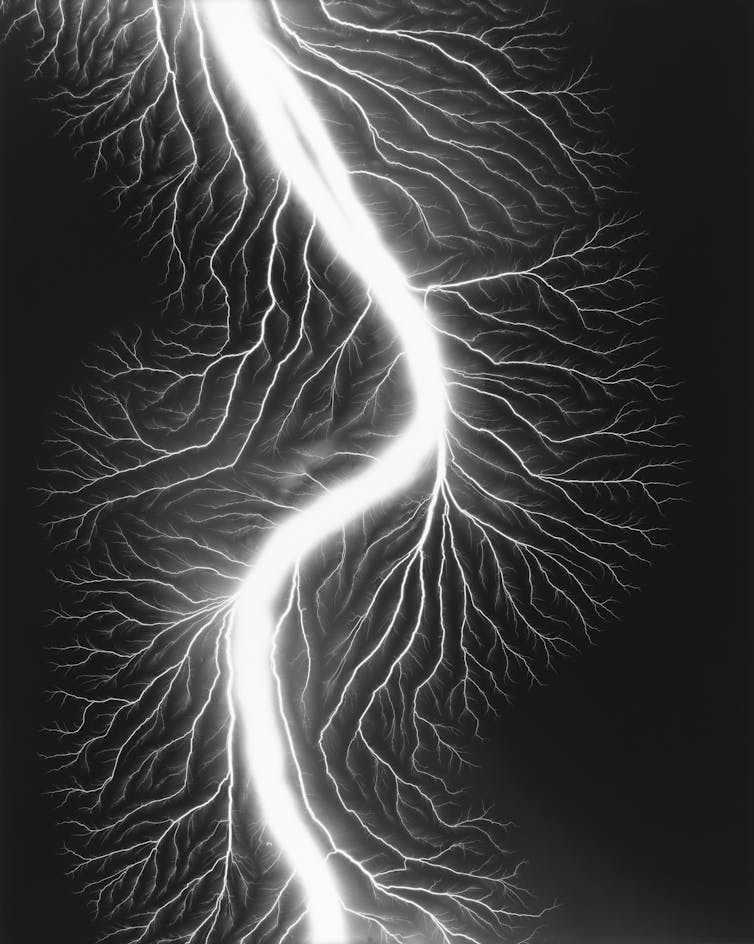

Sugimoto’s work engages with the history of photographic materials and processes. His Lightning Fields (2006–) prints are camera-less photographs, images made through the direct use of light or chemicals on light-sensitive paper or film.

These images gesture to William Henry Fox Talbot’s early experiments with static electricity: Sugimoto’s photographs are the outcome of electrical currents meeting unexposed film. The prints feature dramatic forms that look like splayed branches, sprawling veins or plant roots: fireworks on paper.

Grandness askew

At first glance, many of Sugimoto’s photographs direct attention to the legendary and the monumental: they picture Modernist architecture, portraits of royals and infamous leaders, and wild animals poised to hunt.

But they tilt instead towards less certain territory. Through Sugimoto’s use of bokeh, or blur, the Eiffel Tower in his Architecture series is out of focus.

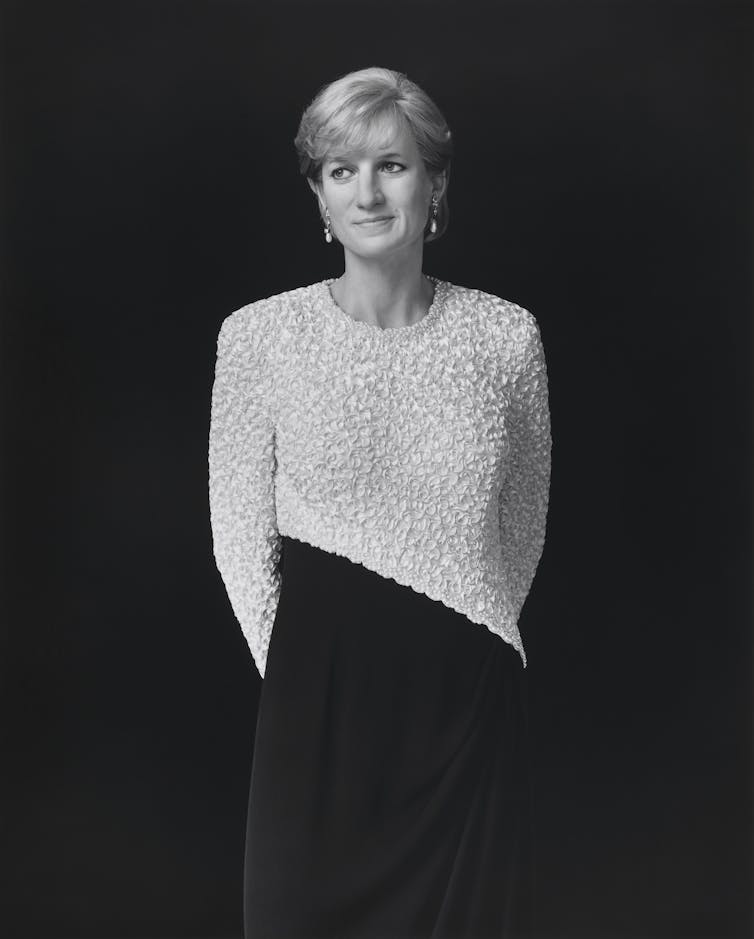

The beautifully lit portrait of Princess Diana, hands behind her back and looking away from the camera, is of her wax likeness: a portrait made at Madame Tussauds two years after she died.

The proud polar bear about to dive on its prey is a photograph of the enclosed space of a diorama: the animal forever poised before the meal it will never have.

Sugimoto’s lens underscores eminence and beauty with uncertainty about the appearance of reality. His work raises questions about where existence begins, ends, or transforms.

The skin between life and death, monument and ruin, surfaces in many of Sugimoto’s photographs. Sugimoto’s “time machine” moves between time gone, spent time and a sense of being beyond time.

A tiny room in the centre of the exhibition – relieved from its usual role as a storage cupboard – contains the exhibition’s smallest prints. This tight space, with its industrial lighting and exposed air conditioning ducts, is a fitting stage for Sugimoto’s Chamber of Horrors (1994). This series features wax figures of infamous murders and their instruments of torture and death.

The claustrophobia in the images is replicated in the tiny space.

Small differences

Sugimoto’s on-going Seascape series with their uniform divide between sky and ocean, are quiet black-and-white images. There are no swimmers, seabirds or ships at sea here: simply water, sky and light from the moon or sun. Subtle differences in tone, wave patterns and light reveal themselves with sustained looking.

The vantage point from which Sugimoto photographs is never revealed, although each image is titled by geographic location. Ligurian Sea, Framura (1993) is one of the darkest and most nuanced in tone: a nocturnal seascape lit barely by moonlight.

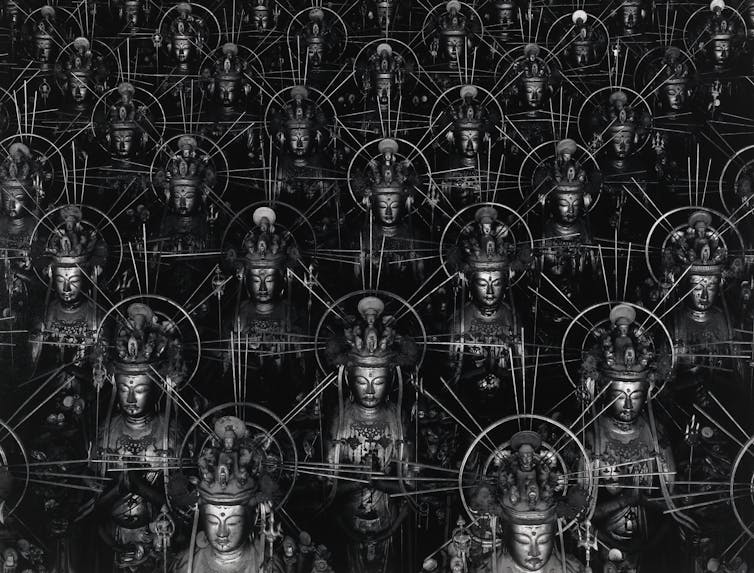

A length of wall features Sea of Buddha (1995). Sea of Buddha is a series made in Sanjūsangen-dō (三十三間堂), a 12th-century Buddhist temple in Kyoto.

These black and white prints share the subtle play of differences in Sugimoto’s Seascapes. Sea of Buddha pictures the 1,001 wooden sculptures of Buddha gilded with gold, a collective of not-quite identical sculptures, small variations revealed through Sugimoto’s lens as light catches the shimmer of gold.

Light and decay

Sugimoto’s celebrated Theaters (1976–) images are made by using an exposure time equal to the screening time of a film. Sugimoto opens the camera shutter as the film begins and closes it only once the film has finished. The result is a luminous screen framed by the interior of a theatre: a single photograph of an entire film.

The detail of these interiors is lit only by the cumulative light from the projected film.

While some interiors in these photographs retain their original ornate décor, Sugimoto’s Abandoned Theatres (2015) document the spaces in varying states of decay.

These images of the theatres’ afterlife are displayed in frames, allowing the patina of ruin to spill beyond the enclosed photographs as the lead oxidises.

The weathering of the theatre interior in Metropolitan Opera House, Philadelphia (2015) is lit by the central luminous film screen. The ceiling is falling in, the side balconies gutted, and a section of the front stage stairs are askew. The decay itself is embalmed, preserved, and transformed by the projected film and Sugimoto’s camera.

This section of the gallery spaces also contains Sugimoto’s Drive-Ins series. In these photographs, the outdoor cinema screens, through Sugimoto’s long exposure, light up exterior spaces.

In Tri City Drive In (1993) the projected film lights the empty playground in front of the screen. A set of swings and slides sit unused. The sky behind the screen contains lines of light: the result of stars and planes moving across the sky during the film’s duration.

The sky is yet another screen for the play of light to be transformed by the machine of time, Sugimoto reminds us.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until October 27.

Jane Simon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.