These days Peter Gabriel is a slaphead out of necessity. Or, as he puts it, due to “the absence of follicles”. But back in 1978, when having a shaven head at best marked you out as part of the boot-boy skinhead culture and at worst identified you as a Nazi sympathiser, Gabriel took a razor to his mop out of choice.

The fact that he would stand on stage clutching a pink teddy bear while singing Me And My Teddy Bear added to the whole incongruous image. “That was actually the first song I ever performed in front of an audience,” Gabriel told Classic Rock in 2014. “The contrast was deliberate. You want to believe that packaging isn’t the main priority for making initial decisions about people, but sadly it is. So by changing the packaging I was hoping to change the perception.”

And did you? “To an extent. I think it worked in America but in England I don’t think I’ve ever outgrown that middle-class, ex-progressive rock persona.”

Strange but true. Most people’s first acquaintance with Peter Gabriel dates back to the mid-80s and the Sledgehammer video that brought a touch of class to the rapidly expanding MTV channel and dropped him right into the laps of a new generation. And yet 29 years after he walked away from his original prog-rock persona in Genesis, the ghost still lingers.

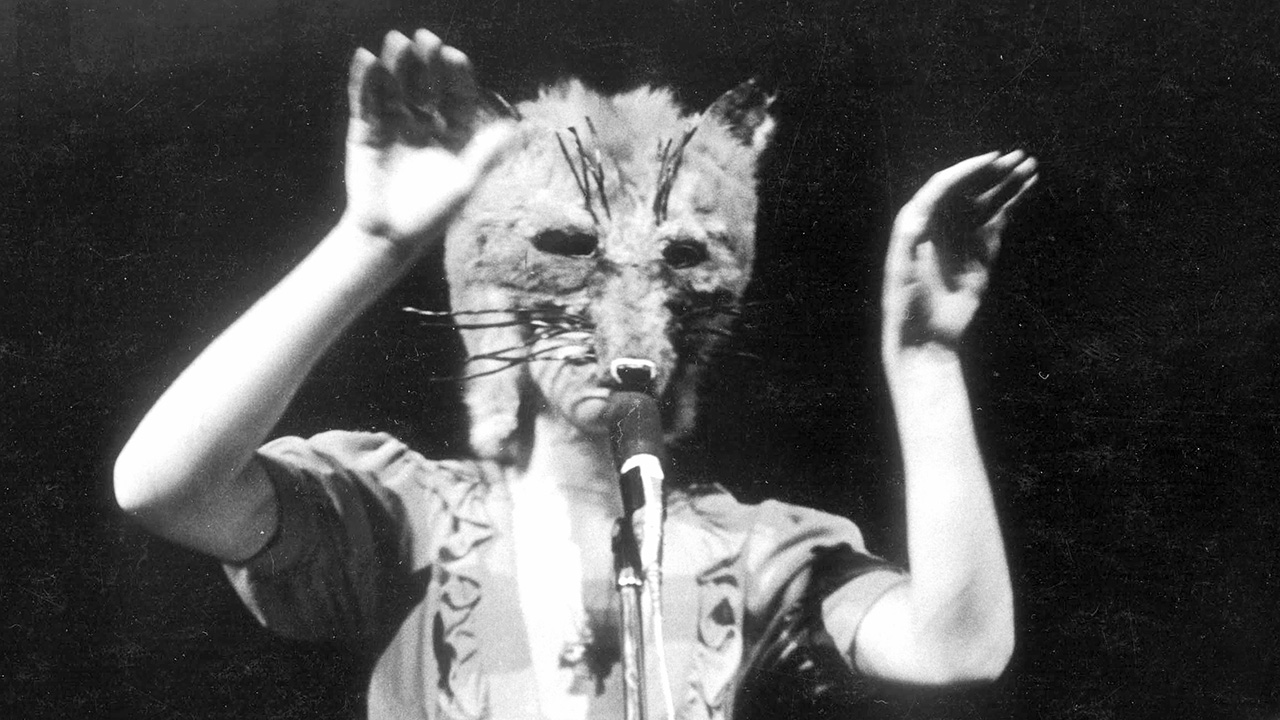

It’s not too hard to establish some kind of link between the middle-aged chap walking around upside down on stage singing Downside Up on his latest tour and the same bloke stuck inside a fox’s head wearing a long red dress back in 1972 singing Watcher Of The Skies.

The connection is Peter Gabriel’s sense of the dramatic. It’s what got him hooked on rock music back in the mid-60s when he was a pupil at the stuffy, class-ridden Charterhouse public school where rock’n’roll was considered subversive. (If you want to sample the flavour, try Lindsay Anderson’s 1969 movie, If – Gabriel auditioned for a part, although he didn’t get it.)

Gabriel isn’t normally one to get reflective about his career. Not when there are Bonobo apes to interact with. Not when the internet is transforming the music industry, giving artists the opportunity to take more control of their work. (When he suggested a couple of decades ago that people would soon be accessing music via the telephone he was laughed at.) Not when there’s an award-winning stage designer finding a way of enabling you to walk upside down on stage and an award-winning director to film you doing it.

But sitting in a cosy corner of the Covent Garden Hotel restaurant, Gabriel is allowing himself to wallow in a little nostalgia.

Gabriel’s formative rock’n’roll experiences outside the gates of Charterhouse – frequently illicit, which only added to the thrill – were Otis Redding and The Nice. “I got to see Otis Redding in 1967 at the Ram Jam Club in Brixton. It was a bit of a moment for me,” he recalls proudly.

“I’ve never really been a technical singer as such, or a musician. I’m someone who goes for the feel of something and tries to build pictures. And hearing the voice and the emotion of Otis Redding was just beyond words.

“I saw The Nice several times as well. I always thought The Nice got branded by ELP in some ways. There was a time when Jimi Hendrix wanted to join The Nice, and nowadays people might look back and wonder why, but if you saw The Nice they were exciting both musically and in terms of showmanship, which I think was part of the appeal to Hendrix.

“When we [Genesis] wrote The Knife, that was very much inspired by [Genesis keyboardist] Tony Banks’s and my enthusiasm for The Nice. Terrible name, though. But then words were never Keith Emerson’s strong point,” he adds.

But that was a couple of years down the line. Back inside the Charterhouse gates, simply forming a band was regarded as an act of rebellion against the establishment, regardless of how whimsical the early efforts of Gabriel, Banks and their school mates Michael Rutherford and Anthony Phillips actually were.

Their early band names – The Anon, the Garden Wall – are testament to their diffidence, although musically they were well-organised from the start. Gabriel had suggested they call themselves Gabriel’s Angels, which could have laid him open to Keith Emerson-style criticism, but the others were not impressed.

In fact they were given the name Genesis by Charterhouse old boy Jonathan King, who was the first to spot their potential. He’d had a hit in 1965 with Everyone’s Gone To The Moon and it wasn’t as if they had many other contacts in the music business, so they sent him a tape. King recorded their first album in ’68, From Genesis To Revelation on the Decca label, which almost nobody bought.

But they knew they could do better, and once they’d wriggled out of King’s clutches they took themselves off to a country cottage just outside Dorking where they spent six months eating, sleeping and rehearsing. Apart from taking afternoon walks they never left the place. As Mike Rutherford later observed: “We were far too intense to enjoy ourselves.”

It meant that by the time they started to play gigs they had a carefully prepared show. But at this point Gabriel became aware that he was the only one standing up on stage. “And the others had absolutely no understanding of the stress that it put on me,” he recalls. “Because I was the one who was actually having to sell it at gigs.

“And it was a lot of pressure,” he continues, “because there were audiences that weren’t the least bit interested in what we had to offer. What’s more, we had all these 12-string guitars that had to be retuned between each number. They’d be sitting there in silence, tuning up, and I’d be trying to speed it up because I could feel the energy from the audience just dissipating. That’s when I started, out of desperation, telling stories.”

Gabriel’s monologues soon became a feature of Genesis gigs as the band built up pockets of support in places like Aylesbury, Godalming and Bath. But progress was painfully slow. Despite package tours with Lindisfarne and Van der Graaf Generator – Genesis’s labelmates at their new home on Charisma – the band’s Trespass (1970) and Nursery Cryme (1971) albums sold pitifully few copies.

“We were plodders,” Gabriel admits. “I remember, after we’d been going for two or three years, talking with this guy who said he was forming a band called Curved Air. And within about three months they’d shot past us into the charts. We were quite depressed that they could do far more in a shorter space of time than we could.”

But then Genesis had very little in common with their rock’n’roll peers. While other bands would head down to the fish and chip shop or the pub after setting up their gear at a venue, the Genesis chaps would get out their lunch boxes and chow down on their egg-and-cress sandwiches.

Sex and drugs were not a prime motivation for their rock’n’roll, either. “We had read about those things,” Gabriel observes. And as for the drugs: “I had the odd experience with hash cigarettes and walked around with the giggles or threw up. It wasn’t doing it for me. Part of it was that I had a very vivid imagination and I didn’t really want to lose control.”

Genesis were even different from other prog-rock bands. They took a democratic, collective approach to their music, and there were no wanton displays of instrumental flamboyance. “It was much more a composer’s approach rather than a player’s approach,” Gabriel agrees. “Some of the other bands were better players than us but didn’t have the same approach that we did. Tony and Steven [Hackett] would have their moments but they were all within the group context.”

Another problem for Gabriel was that while his vocals provided much of the songs’ foreplay, the climaxes were often instrumentally driven, leaving him standing around, useless and frustrated. “The most I could do was to bang a tambourine. Actually, I should have been utilised on a keyboard or some other instrument, but that was all down to politics within the band.”

For all the musical drama Genesis could conjure up, it wasn’t until they developed a visual element that they started getting recognition. Gabriel had tinkered with eyeliner and shaving a wedge out of the hair above his forehead. Then he donned his wife’s (he got married in 1971) Ossie Clark designer dress (“It was a struggle getting into it”) and a fox’s head for a show in Dublin in October 1972.

“Back then Ireland was not the hippest country in Europe,” Gabriel says, with understatement, “and there was a palpable sense of shock as I walked out on stage. I thought the dressing up was fun, but the rest of the band were pretty uncomfortable about it. There was a lot of heavy discussion about whether I should be doing this sort of stuff. But I’m an obstinate bugger, particularly when people don’t want me to do something.”

Just as the others jealously guarded their instrumental domains, Gabriel protected his wardrobe. “When we started the Supper’s Ready tour I didn’t show the band any of the visual things I’d planned. I thought: ‘If these masks come up for band discussion they won’t go with it.’ I knew it would work, but I was going to have to do it furtively.

“I brought them along to the rehearsals on the day of the show. And I think the others realised at that point that they couldn’t stop me because it was too close to the show and it would really rock the boat. Fortunately the audience reacted well and I got away with it, although it was a close-run thing.”

The masks included a geometrically enhanced cardboard box, and a faintly ridiculous flower ensemble with Gabriel’s head framed by petals. With the addition of a white muslin curtain behind the band, lit by ultra-violet lights, the audience now had something to focus on apart from their own shoes.

Through 1973 and 1974 Genesis developed a cult following. They had already become big in Belgium and Italy, and their new musical tales of mystery and imagination on the Foxtrot and Selling England By The Pound albums proved particularly popular in the industrial towns and cities of northern England. They even almost had a Top 20 hit with I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe), but it stalled at No.21. And when they started touring America, their strongest areas were the blue-collar cities of the US Midwest and Canada.

“I think some of them were trying to escape from their backgrounds, and we had a romanticism that cut through to people,” Gabriel explains. “We were much more Harry Potter than The Terminator. The critical thing for me was how much feeling we were able to put out, and I think there was a real emotion getting through at our gigs.”

Emboldened by the band’s success, Gabriel’s stage outfits became more elaborate. On a couple of occasions he was even hoisted into the air on a wire to sing The Musical Box.

He also started getting more possessive over the lyrics, which caused ructions with the others who felt that words were part of the ‘group thing’. Gabriel didn’t help himself by being late with the lyrics. So it was with some reluctance that the rest of the band allowed Gabriel to write the lyrics for their conceptual tour de force The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, even though it was his concept.

“I insisted, although there were two songs in which the others got involved because they didn’t want it to be a hundred per cent. And I think that really was the reason, although they would probably give you other reasons. But I did put a copyright on the little story I wrote on the sleeve, jumbled as it is, because while I was an equal contributor on the musical ideas I knew that I was doing a lot of this work in addition. It was pure ego.”

Ego – or the flattering of it – also had a part to play in the episode that nearly wrecked Genesis during the recording of The Lamb… The Exorcist director William Friedkin had read an earlier surreal story by Gabriel on the sleeve of their Live album, and got in touch about writing a script. Already behind with The Lamb… lyrics, Gabriel asked the group for time off. When they refused, he quit. Matters were resolved only when their management warned Friedkin that he was breaking up the group. Friedkin backed off, and Peter sheepishly returned.

More traumatic was the birth of Gabriel’s first daughter, who after a complicated birth was in intensive care. “We were recording in deep Wales,” he recalls, “and my daughter was between life and death in Paddington. So there was this five-hour drive to visit my wife and daughter. It was absolutely exhausting.

“The rest of the band were sympathetic but they couldn’t understand. The Band had always been The Boss and our duty. Our life was our work, and any kind of life outside this all-consuming entity, whether private or professional, was something the others found pretty threatening.”

His daughter survived (and in the mid-noughties made a movie of her dad on tour), The Lamb… was completed after round-the-clock mixing sessions, tours were booked, and a new show conceived and prepared. But Gabriel’s perspective had changed irrevocably. Four dates into their US tour in late 1974 he told the band he was leaving, although it was another six months before he could extricate himself.

“Our manager was booking tours 18 months ahead, which is normal business practice, but I was just feeling the whole weight of commitment and thinking, when is life going to happen? Is it all just tours and records? I wanted to stop every now and again and have time with my family. But you couldn’t because it was fucking up the band.

“And the irony was that I had all that really strongly when I said I wanted to leave, because we hadn’t paid off our debt and things were really beginning to take off and now I was fucking it up for them. So the reason I stayed with the band for a European tour was guilt.

“And the thing that was hardest for me was that I had agreed that in order to give the band a chance to build a new identity I wouldn’t say anything for another six months. And I felt like a fraud. I was performing in front of all these people and I couldn’t say anything. But strangely enough I was more confident that they would do all right without me than they were.”

But the press and public didn’t see it that way. When news finally leaked out and Gabriel wrote a “convoluted letter” to the press, Genesis found themselves reading their own obituaries while everyone speculated on Gabriel’s next move.

Except that there was no next move. “It was time out rather than time off,” he explains. “After I left Genesis I wanted to be outside the music business. At first I was just growing vegetables and looking after the baby. I also looked at this commune that I was actually quite serious about joining. They’d put together different elements of spiritual traditions, and they auditioned prospective members with psychological testing and stuff like that. It was quite a weird experiment. Even weirder, it was called Genesis!

“But the more I was without music, the more I realised I still loved it and I wanted to get back. And they said: ‘If you do go back, we can all decide when you should go.’ And I thought, hang on a minute.”

Having rejected Genesis for a second time, Gabriel got back into the swing of writing songs. But who to play with? Apart from his old band, he hadn’t really hung around many musicians, although he had got to know Robert Fripp, the leader of King Crimson, and a London-based American keyboard player called Larry Fast. For Gabriel the prospect of forming a band was daunting.

He ended up going to Canada to work with Bob Ezrin, on the face of it a strange choice. Ezrin had made his name producing Alice Cooper and had recently worked with Lou Reed and Kiss.

“One of the attractions of Bob was that he seemed really good at organising people, and it was nice to feel that some of that pressure was not going to be on my shoulders,” Gabriel explains.

“I was very nervous doing the first sessions with him so I took my little English contingent with me, and he introduced me to these other musicians, one of whom was Tony Levin, who has been my bass player ever since.

“Bob helped enormously. He’s very talented. We still work together on projects. But at that time he was also a bit of a coke-inspired control freak. And that would manifest itself in various ways. There was one particular occasion when a beautiful guitar solo from Robert [Fripp] was erased and we didn’t quite know why. And that created tension.

“Then there were the sessions for Here Comes The Flood, when I wasn’t sure about the drum part so I wanted it isolated so I could erase it if necessary. But when I listened back the drums had been mixed in with the orchestra, and there was no way I could get rid of it. There were several moments like that. But we found a way through, and I think there are bits of that album [the first Peter Gabriel] that are really good and focused. There’s just a few bits where it goes off the rails.”

By now it was 1977 and, as Gabriel had predicted, Genesis had already risen, phoenix-like, and were more commercially successful than ever. Suddenly it was ‘Peter who?’ Thank goodness, then, for Solsbury Hill which gave Gabriel a Top 20 hit and the exposure he needed to launch his solo career. “That was something Bob Ezrin kept pushing me to finish. He’s very good at motivating people to get on with writing.”

His first tour that year put further distance between him and his former band – no dramatics, no costumes, just a simple but effective light show. “I was definitely trying not to play Genesis songs, although I did do Back In New York City [from The Lamb…]. And there were a couple of covers – Marvin Gaye’s Ain’t That Peculiar and The Kinks’ All Day & All Of The Night – which were outside the prog-rock background I was associated with.”

He had also been thinking about the barrier between the performer and the audience, and “how much more interesting it could be if you tried to break through that”. The newly developed radio microphone gave him the first chance: he’d disappear off stage during the introduction to Waiting For The Big One and reappear at the back of the stalls or the balcony before making his way back to the stage through the audience.

“You couldn’t pre-programme the show if there was a physical interaction with the audience,” he explains. “They could determine how long you were out there. It certainly added a sense of alive-ness to the show. Because I was putting myself in a place that was potentially vulnerable. And things like trust start to come into play.” Later on he would take that a big step – or fall – further.

Having put clear daylight between himself and Genesis – and had a hit single as well – Gabriel now had to decide which way to go on the next album.

“I was worried about getting drawn back into the pop thing. So the second album was a deliberate attempt to go somewhere else, and I asked Robert Fripp to produce it. He said: ‘That’s a wonderful idea. We’ll do the whole thing in six weeks. No pussyfooting around.’ I thought that sounded exciting and I decided to go for it.

“But what I learnt was that I don’t do good work in a hurry. I may get moments of things, but not a proper body of work. The songs weren’t as good as they could have been, the lyrics weren’t as good as they could have been, the arrangements certainly weren’t as good as they could have been, and the sounds weren’t as good as they could have been.

“It took until the next record to find out what I was as a solo artist, or could be. That was in the framework of feeling more settled with the band, and having the great team of [producer] Steve Lillywhite and [engineer] Hugh Padgham.”

The framework for that third album also included an odd rule: no cymbals. “I’d been thinking about the things I didn’t like on rock records,” Gabriel explains, “and one of the things was cymbals splashing around all over the place. They take up an incredible amount of space in the higher sound frequencies. And if you take them out you give yourself a whole country to explore.

“So I said no cymbals. And that meant that the drummers – mainly Jerry Marotta but also Phil Collins and Morris Pert – couldn’t do what they normally do. Suddenly they had to think differently. And that affected the spine of the piece, the rhythm. And everything else.”

Out of that quest for new and different drum sounds came the gated reverb, an effect that engineer Padgham had tried out on an XTC album shortly before. “He was playing with it in the studio, and I got quite excited and asked him to turn it right up. I remember saying: ‘This is going to revolutionise drum sounds.’ I wanted to do a track that was entirely based around that sound. And that track was Intruder. Phil was playing on that track and he got excited by it too.

“It’s a minor thing, but when people listen to that song and say: ‘You took that Phil Collins [In The Air Tonight] drum sound,’ that niggles me.”

That sound gave Gabriel’s third album a potent, if ominous, sound that ran from the opening Intruder through to the closing anthem Biko. Even the poppy Games Without Frontiers had menacing undertones. It was all too much for Atlantic Records in America, who decided to pass on the record. “Apparently after they heard Lead A Normal Life they asked my manager whether I’d been in a mental institution,” Gabriel says. “The head of A&R, John Kalodner, kept wanting me to sound more like the Doobie Brothers, who were very popular at the time.”

The album – his third to, confusingly, be titled simply Peter Gabriel – turned out to be his most successful so far in both the US and the UK, justifying his barbed comment about Atlantic’s “short-sighted and bigoted attitude”.

But it worked. Sledgehammer was a worldwide hit – No.1 in America – and the So album topped the UK charts and spent three weeks at No.2 in the US. Finally, Gabriel was a star and, having kept the music business at arm’s length for 20 years, suddenly he went high-profile, turning up at awards shows.

“I’d avoided all of that stuff and had a very pure, Stalinist line against the business, but I did embrace the selling of my music at this point, and I didn’t really feel much the worse for it. I didn’t feel that the angle of bending over had exceeded my natural comfort zone,” he adds with a smile.

The This Way Up date schedule included all but one of the So songs, and expanded the light and space concepts from the previous tour. This time Gabriel used mobile lighting cranes, which were at their most effective when they crowded round him while he sang Mercy Street. And the rousing duet with Youssou N’Dour on In Your Eyes was an inspired piece of world music alchemy.

Gabriel was reaching a new audience, drawn in by the videos and his media profile. “It was a pop audience that I hadn’t had before. And I’m afraid some of the cult followers were not very happy to share with the casual viewers,” he recalls.

“And then, just as everything was beginning to wind down, the album got another boost from the Say Anything movie, with John Cusack holding up a radio playing In Your Eyes as a Valentine’s Day offering for his girlfriend. You never quite know when these external events are going to help or hinder you.”

Typically, Gabriel managed to dissipate much of his new-found rock-star status by taking six years for the follow-up, Us. Admittedly there was another soundtrack (Passion) and a compilation (Shaking The Tree) in between, but he acknowledges an almost wilful intent: “I have tended to follow a successful album with a less successful album. I think I’ve protected myself with obscurity whenever I was threatened with success.”

On stage Gabriel, who had now gone skinhead, continued his walkabouts, sometimes ‘surfing’ the audience on a piece of plywood which was carried along by four strong roadies acting as pall-bearers. When he occasionally fell off, the audience, far from ripping him to shreds in a frenzy, helped him back on to the board. From that developed the idea of deliberately falling backwards into the audience from the lip of the stage.

“I’d done those hippy psychological games, falling backwards and trusting people to catch you, so I thought I’d do that on stage and hope that they caught me. When you go forwards that’s one thing, but when you go backwards it’s another completely. For the most part I got caught. But early on, in San Francisco, they thought: ‘This must be part of the act. We’d better move away.’ And that hurt!”

Even when they caught him the audience were not always reverential. “I was debagged on a regular basis. And in Chicago I barely held on to my underpants. I clambered back on stage holding my belly in as best I could. Later on I saw an REM video where Michael Stipe dives into the audience and I thought: ‘Damn, I should have done the video while I was ahead.’”

Gabriel’s stage-diving antics began on the mysteriously named Tour Of China 1984 – it was only 1980 at the time. “Well, there was this big thing about who would be the first rock act to play China. I knew I wasn’t going to be the first, but I thought I might as well do the merchandise. And 1984 always struck me as a scary year ever since I read the book.”

The closest Gabriel actually got to China was when the Tianjin Song & Dance Ensemble performed at the first WOMAD Festival in 1981, which he was heavily involved in. That event is now seen as the catalyst for the burgeoning world music scene, but at the time it bankrupted Gabriel and exposed him to a few unpleasant realities. Genesis bailed him out with a benefit show the following year.

“People were saying: ‘Who is this fat cat watching us suffer?’ when in fact the debt was far more money than I had to my name. It was extraordinary to see what happened when it all went bankrupt. I got death threats, and the liquidators actually forged a signature of one of the WOMAD directors so they could get their cut of the Genesis benefit concert.”

The Genesis reunion concert at Milton Keynes the following year paid off the debts, but Gabriel emphasised the one-off nature of the reunion by entering and leaving the stage in a coffin.

His own enthusiasm for world music was evident from the opening track of his fourth Peter Gabriel album (titled Security in America), The Rhythm Of The Heat. “I’d been working with this Ghanaian drum band, Ekome, in Bristol, and that’s where the final section of that song came from. Getting that change of rhythm down was incredibly exciting – one of those moments when you think: ‘Nailed it!’ A great feeling.”

The unrelenting intensity of Gabriel’s fourth album – musically even the hook-laden single Shock The Monkey was like a coiled spring – scuppered its chances of being his breakthrough album. “It wasn’t a big seller,” Gabriel confirms. “Some of the hardcore fans think it’s the best record but others thought it was too wacky. Maybe that’s because I was taking a bigger role in the production.”

The complex and sometimes impenetrable videos didn’t help, either. But live the musicians had developed into a cohesive, energetic unit that attacked the songs’ dynamics with a cavalcade of synthesised rhythms and loops. The stage was sparse, the lights white and bright, and ‘the dive’ took on an almost religious significance. David Bowie was so impressed that he took Gabriel along with him on the North American leg of his Serious Moonlight ‘comeback’ tour in 1983.

Gabriel began work on the next album the following year, but got waylaid by soundtrack projects for Birdy, Against All Odds and Gremlins, not to mention domestic strife and temporary separation from his family. But when So finally emerged in May 1986 it was emphatically a case of right record, right time.

“It exceeded all our expectations, in terms of making music as well as commercially,” Gabriel admits. “I had hooked up with Daniel Lanois, who co-produced the album with me, and all the elements were fitting together. But then it’s always easier to look back in hindsight. I mean, even though Sledgehammer felt strong and the groove was great it didn’t feel like a big hit record. People go: ‘You must have known it was the commercial track,’ but it wasn’t until we started doing the video that we got a feeling about it.”

The Sledgehammer video was when Gabriel’s complicated ideas were made accessible. “I think it was looking forwards and backwards at the same time,” he muses. “People think it was done with a lot of computer effects, but it fact it was old-fashioned animation techniques. It was a slow, tortuous process. And the day I spent surrounded by stale fish that had been under the bright lights the day before was not a sensual experience I want to repeat.”

Us may have sold only around half of what So did, but it probably wouldn’t have sold much more even if it had come out four years earlier. Where So was direct and accessible, Us was pristine but introspective. The cult following had their man back again. “I didn’t feel the production caught the energy sometimes, but I felt good about the songs,” Gabriel reflects.

The accompanying Secret World tour was an ambitious leap into the unknown. It was the brainchild of acclaimed designer Robert Lepage, who, Gabriel says, “creates theatre for people who go to the cinema. It was not just about words and performance, it had what I call a high moisture content – a mysterious environment, if you like – and I wanted to see if we could incorporate that into our show.”

Set in the round, the set had two stages with a walkway between. “There was the male square stage and the female round stage, and obviously some random stereotyping in that sense,” Gabriel explains. “But having two places to go, the feeling of playing two stages, was quite different from the usual show where everybody’s pointing the same way and the energy is going in the same direction.”

But despite the show’s complexity there were no dazzling affects to wow the audience. “A lot of acts were in the ‘weapons race’ back then: how many lights you can have, that sort of thing,” Gabriel says. “We went out with about a tenth of the weapons of some of these bands, but we were trying to use them in a more interesting way. I think it’s an important distinction; it’s not all about quantity.”

Some of it was about choreography, though, given Lepage’s theatrical background, and some of the band had to learn to skip in unison. But skip they did as the Secret World tour traversed the globe for most of 1993 and 1994, visiting countries off rock’n’roll’s beaten track like India, Egypt, Chile and Venezuela.

The six-year gap between So and Us paled in comparison to the 10-year wait for Up, which eventually arrived in September 2002. “It’s a bookends record,” according to a 50-something Gabriel in 2004, “looking more at the beginning and end of life than the middle.”

Songs about death (I Grieve) and childhood fears (Darkness) may not be obvious rock’n’roll subject matter, although they are broken up by some thunderous metallic beats and rhythms, as well as the life-affirming More Than This and a caustic satire on reality TV (The Barry Williams Show).

“To begin with, Up got some really bad reviews,” he admits. “Rolling Stone gave me a stinker, which was quite disappointing because I felt I’d worked bloody hard at it and it has some of my best work. It’s taken a while, but recently I’ve had musicians come up to me and say it’s my best record. Which is some consolation.”

And if they didn’t like the record, the critics have been effusive about the latest Still Growing Up tour. Last time, Lepage and Gabriel spread out horizontally, this time they’ve gone upwards. “We decided to try and create levels and variations vertically, so that you end up effectively with a heaven stage and an earth stage and a means of moving things – and people – up and down.”

Which is how Gabriel and his daughter Melanie come to be walking upside down on the underside of heaven, singing Downside Up (from Gabriel’s OVO Millennium Dome show).

“Actually I was dreading that,” Gabriel confesses. “While Robert and I were working on the idea someone had actually fallen. And my daughter was going to be asked to do this, so I wanted to make doubly sure it was safe. The first time she did it live I was very emotional. I was wanting to be protective and supportive but at the same time I just wanted to sit back and enjoy it.”

The Still Growing Up tour does have some gadgets to impress the audience: the Zorg ball, a huge, transparent hamster wheel inside which Gabriel walks while singing Growing Up. His original intention was to walk out over the heads of the audience in a novel departure from his earlier stage diving. “But it was pointed out to me that the combined weight of the ball and my not inconsiderable weight might flatten some smaller members of the audience.” There’s also the jacket of lights that he wears for Sledgehammer, and the bike he rides around the stage while singing Solsbury Hill.

“One of the things I enjoy most is brainstorming with interesting people,” Gabriel says, “and doing a very visual tour gives me the chance to do that. The big production stuff is something I‘ve always enjoyed, right from the early days of Genesis.”

In a wardrobe of his there probably still lurks a red dress and a fox’s head.