“The Finch” is a bright flash of light that appeared on many telescopes on April 10, 2023. To this day, astronomers don’t know what set it off.

The avian moniker belongs to an event scientists spot roughly once a year. It’s called a Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient (LFBOT), and it doesn’t fit the mold of a supernova.

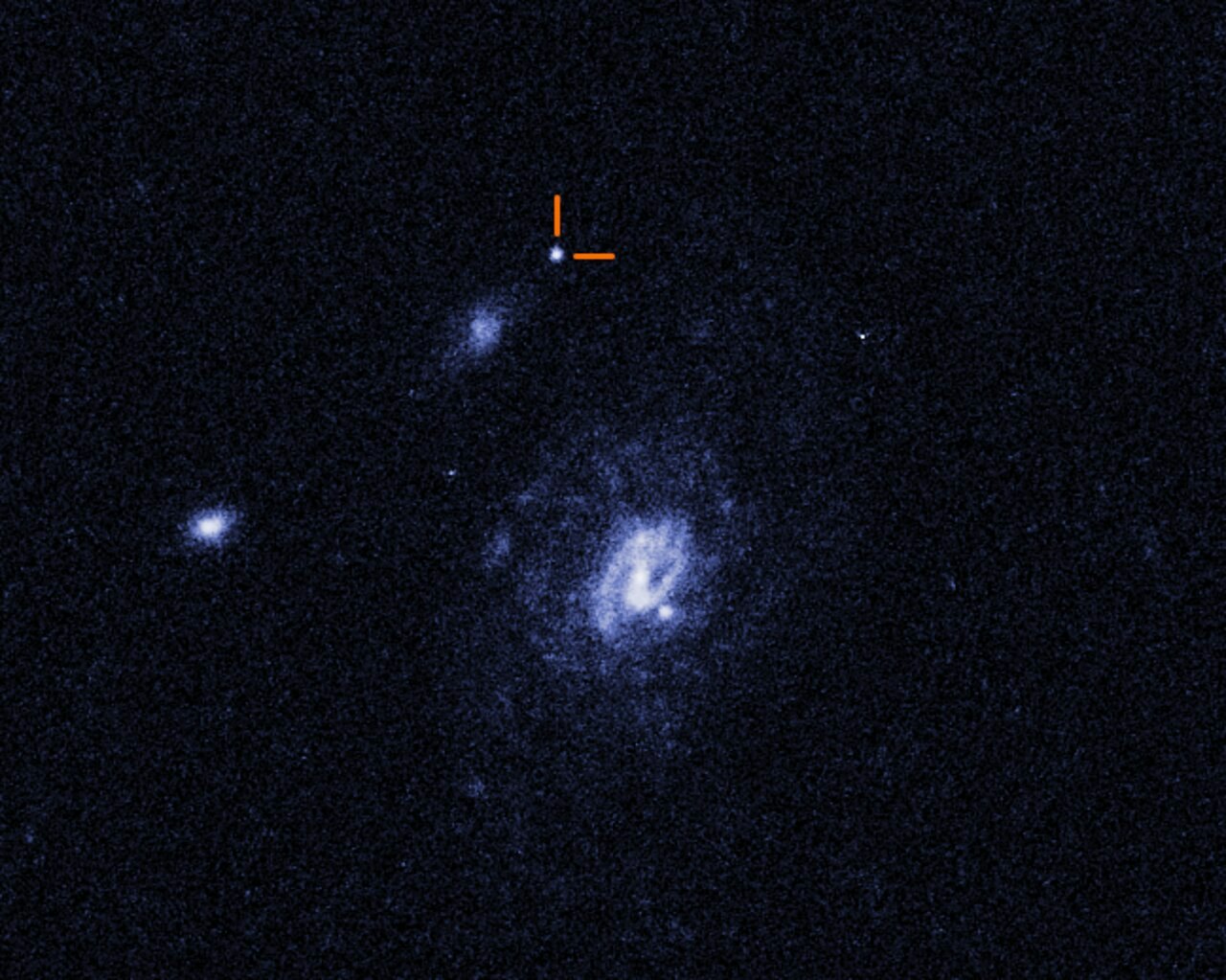

Supernovas create drama, but their sparks are different from LFBOTs. Supernovas take weeks or months to dim; LFBOTs take just days. Supernovas are also explainable: When stars reach the end of their life, they, in one way or another, explode. LFBOTs could be star deaths, too, but while past LFBOTs appear in stellar nurseries, the Hubble Space Telescope found that the Finch emanated from a dark chasm between galaxies.

“The discovery poses many more questions than it answers,” Ashley Chrimes, astronomer and lead author of a paper in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, says in statements from both NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) describing the Finch. “More work is needed to figure out which of the many possible explanations is the right one.”

What does the Finch look like?

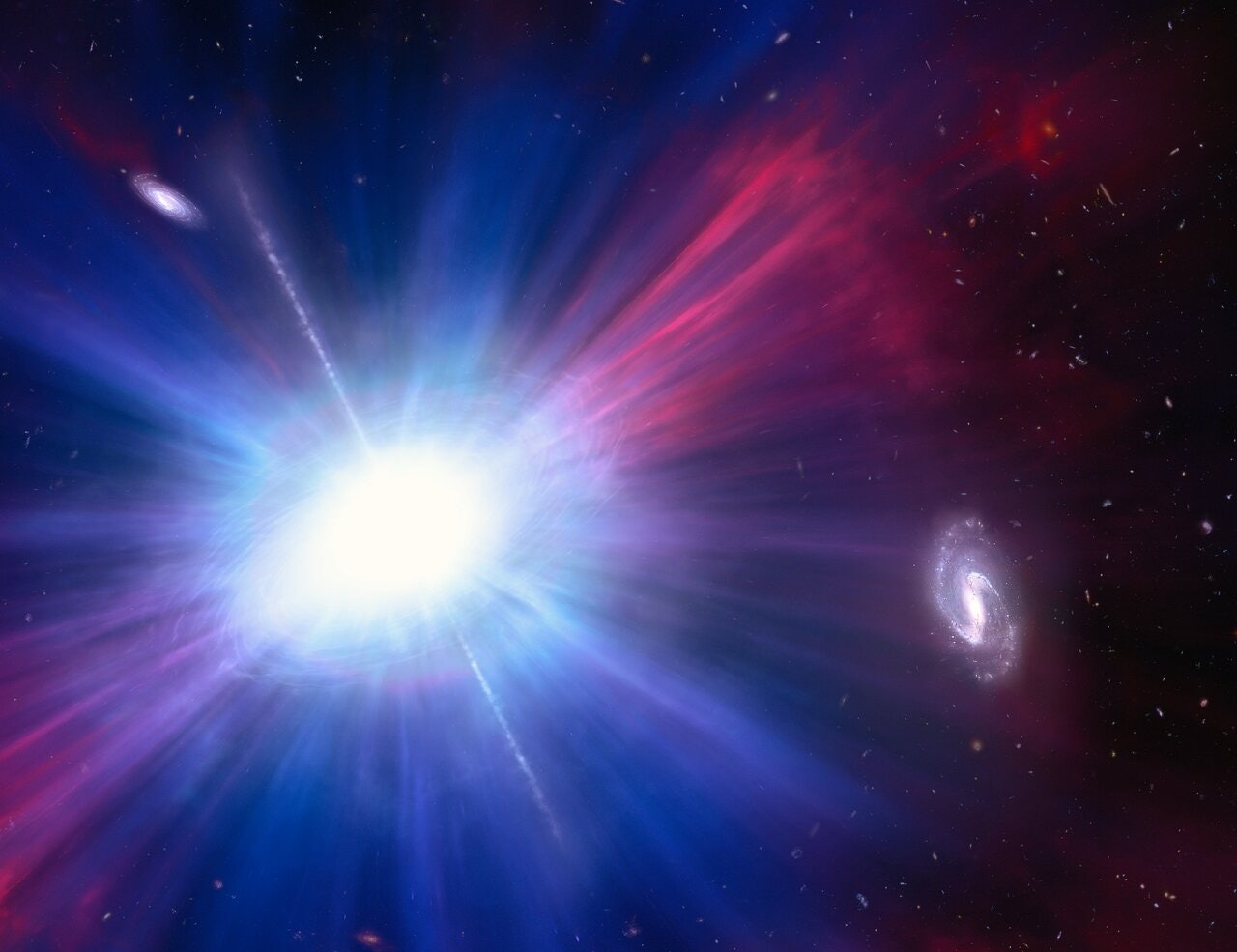

The Finch, like all other LFBOTs, is ephemeral. It shines intensely in blue light and evolves quickly into its peak brightness; then, it's gone. It takes only a few days for them to fade.

They are some of the brightest visible-light explosions in space. The first was discovered only recently, in 2018, and a handful have been observed ever since. With a small sample size, astronomers have limited guesses about their source.

They had an inkling that these phenomenal events could come from places within galaxies where stars were being born based on the location of the past blasts. But the Finch has thrown a wrench into that idea.

It’s “unlike any other LFBOT seen before,” NASA and ESA officials write. The Finch appears outside of two galaxies rather than inside of one. It was 50,000 light-years from a nearby spiral galaxy. Although it was three times closer to a smaller galaxy, the Finch emerged in what appears to be a desolate place.

Even if a star had managed to emigrate out of a galaxy and then exploded, the large blast would have needed to be powered by a large star, and astronomers don’t think one could have survived the exodus.

What happens next?

Astronomers need to grow their LFBOT sample size to get a clearer picture of these mysterious events. All-sky survey telescopes like the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory may help detect more of these short-lived events.

For now, researchers have their theories. Perhaps the dark patch of sky is filled with a community of stars that our telescopes can’t see, but where the fuel for such a blast was dwelling and where a black hole was prowling and, in April 2023, finally pounced.

But we still don’t know anything for sure.