Electronic music pioneer John Foxx has made a 50-year career out of continually changing his sound from glam and proto-punk to new wave/synth-pop, quasi-rave, psych, ambient and beyond. “That was always the plan,” he says. “To make every record different from the last.”

Foxx acknowledges, however, the pitfalls of such an approach. “It can be dangerous,” he says from his home in Bath, laughing. “The most treasured thing in rock’n’roll is consistency, and I’m anything but that. It’s a bit of a problem.”

He once recorded a cover of Pink Floyd’s Have A Cigar – which he admits is the most prog thing he’s ever done. “I liked early Floyd a lot,” he says, but adds that he has another problem, with proficiency, that stretches all the way back to the late 60s.

“The Nice and ELP are, for me, where things went too far into being ‘very good musicians’. Very good musicians, like very good singers, don’t interest me. There’s a point where proficiency blocks musicians off from real adventure because they become so refined they can’t see the value of crudity. The Velvets were always closer to that, I think, than Yes. I groan when I hear really technically proficient stuff. You need expertise, but you need to know when to abandon it.”

Foxx considers progressive music to be anything from Stockhausen to The Shadows – the latter having been a primary influence on Kraftwerk, whom he also loves, along with fellow Krautrock explorers Neu!.

After The Shadows and Joe Meek, his head was turned by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Steve Howe’s Tomorrow, and Syd-era Floyd. Oh, and The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows, which he spent all night playing when he got his copy of Revolver. “It was such a brilliant piece of music, revolutionary in its layout and concept, completely unlike anything else,” he says.

He immediately wanted to replicate that sense of adventure. “Pop music had become a laboratory where you could try anything. It became a vehicle for imagination and experimentation, which is what got me into it.”

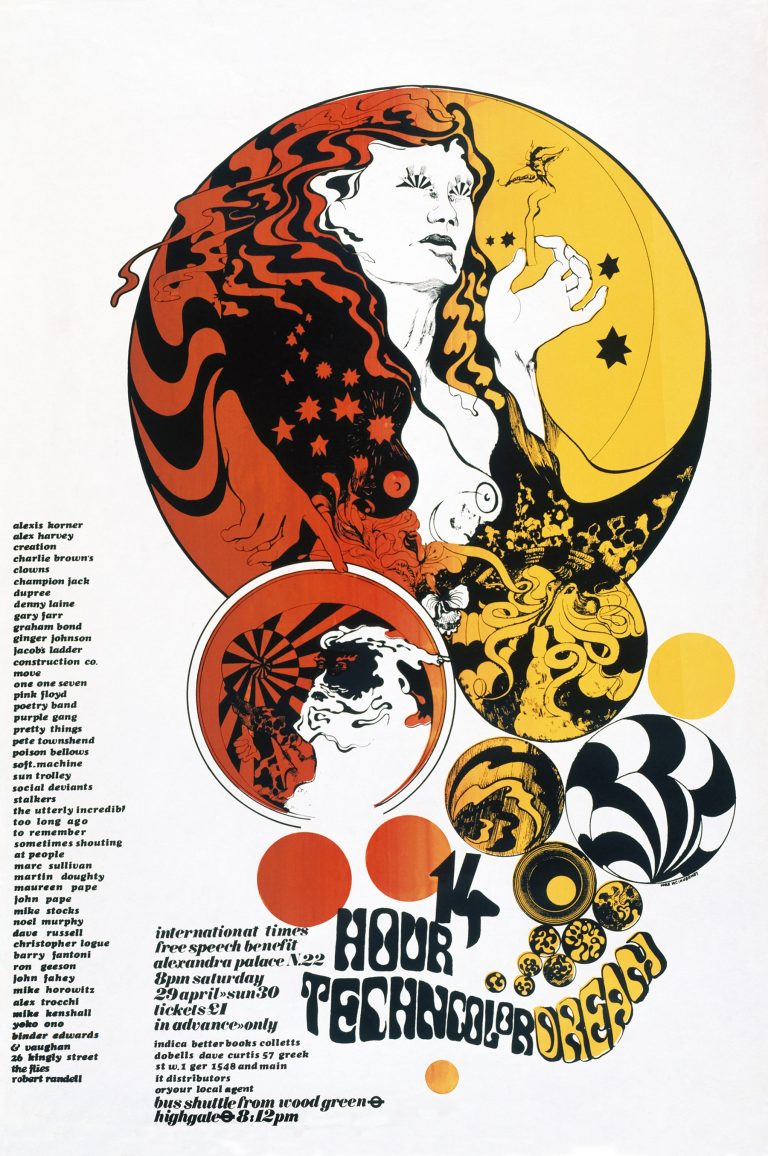

In April 1967, Foxx, born Dennis Leigh 30 years earlier, left his home in Chorley, Lancashire, where he lived with his millworker mother and miner/pugilist father, to attend the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream: a fundraising extravaganza on behalf of countercultural bible International Times, held at Alexandra Palace, featuring poets, artists and musicians. Pink Floyd headlined, while Soft Machine, The Move, Tomorrow, The Pretty Things and many more were on the bill, and the likes of Brian Jones and John Lennon were, Foxx marvels, “just casually strolling about”.

Did he speak to them? “I daren’t!” he says. “It was a really interesting evening because it was the first time anything like that had happened.”

Foxx notes the rapid speed of change from the early 60s – a monochrome era that “still felt like the 50s” – to psychedelia, after which “everything became technicolor” (although the “sunlight and happiness” were enough: he didn’t need pharmaceuticals to enhance the experience).

“It was the most rapidly expanding period ever,” he muses, “a massive period of development, magnificent enough to draw me into it.”

Foxx spent a summer hitchhiking with a friend around Germany and Spain. “This was before psychopaths were invented,” he jokes.

He recalls The Shadows and other such “space music” on jukeboxes, and trying to find Salvador Dali but giving up when they heard he met uninvited visitors with a shotgun.

He formed his first band, Woolly Fish, circa 1967 (his memory is hazy), while doing his Foundation Year at art school in Preston. They played at the city’s Top Rank, where they were introduced as “Preston’s No.1 Psychedelic Band”. He worked as a freelance illustrator, contributing drawings to underground magazine Oz. There were periods at art school in Manchester, and in London, where he attended the Royal College of Art.

“I used to see [Brian] Eno a lot in the canteen,” he recalls, “because he was going out with Carol [McNicoll, who later designed Eno’s renowned black cockerel feathered boa collar] from ceramics. He turned up in full regalia once, which in that environment didn’t attract that much attention.”

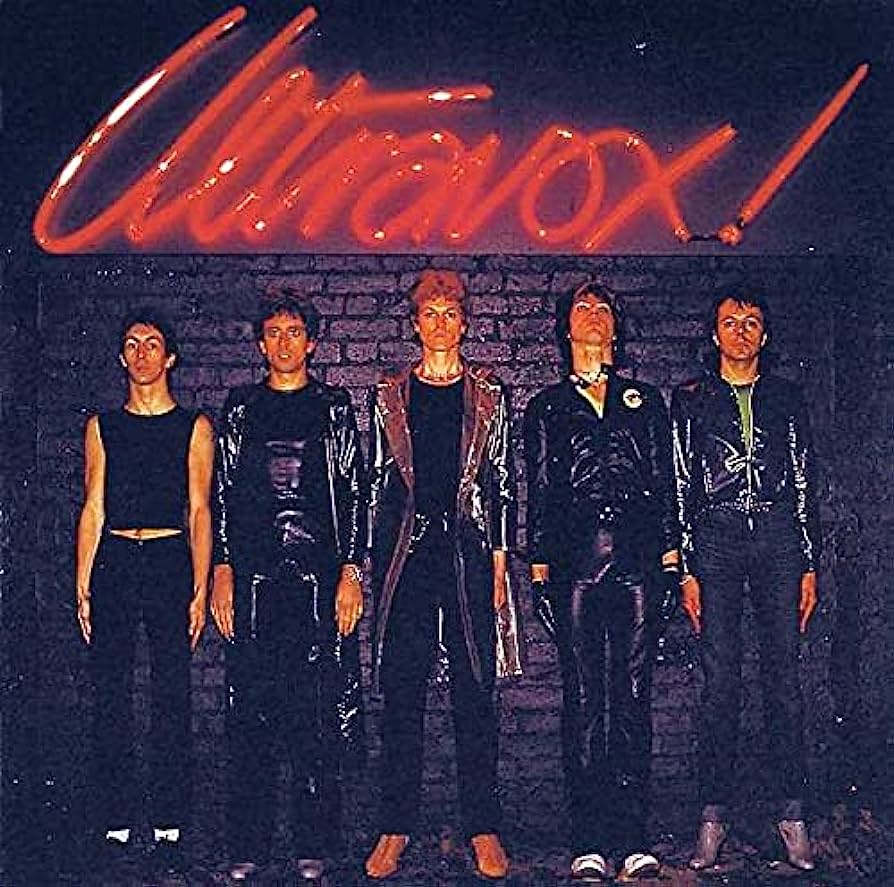

In 1973, Foxx formed another band, Tiger Lily, who might have been part of the late glam wave that also included Cockney Rebel, Sparks and Sailor. They released a cover of Fats Waller’s Ain’t Misbehavin’ and featured several of the musicians who would later be involved in Foxx’s next venture. In 1976, after several name changes, including Fire Of London, The Zips and The Damned (the latter was already taken), Tiger Lily became Ultravox!. At the same time, Leigh assumed a new identity.

“[John] Foxx is much more intelligent than I am, better looking, better lit,” he once said. “A kind of naïvely perfected entity. He’s just like a recording, where you can make several performances until you get it right.”

Foxx was completing his art degree when he went into the recording studio to work on Ultravox!’s self-titled debut album with Eno. Both were signed to Island, and Foxx recalls being drawn to Eno “after he’d been jettisoned from Roxy Music”. The pair would meet at Island where there was “a very sociable environment in the cafe lounge” and “a big West Indian scene” involving Bob Marley & The Wailers and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, “which we all enjoyed”.

Foxx had been impressed by Another Green World (“A form of jazz, but without the clichés,” he suggests) and “recognised the John Cage, Stockhausen and Weather Report influences” and so asked Eno if he’d be up for producing his band’s first foray.

Eno had been credited with “Enossification” on Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway (1974) and with applying a “direct inject anti‑jazz ray gun” to Robert Wyatt’s Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard (1975), but as a bona fide producer, he was a relatively unknown quantity. What did he bring to Ultravox!?

“Ideas, really,” Foxx says. “He was more conceptual. I realised early on that Brian wasn’t that technical – he just had a good way of looking at things. He wasn’t afraid to distort voices and do things conventional engineers wouldn’t do.”

Eno went from producing Ultravox! to collaborating with Bowie in Berlin.

“Brian was, as he always does, playing hard to get, and we were saying, ‘Go on, do it! Don’t be stupid, it’ll be great fun!’ And of course he really wanted to do it.”

It was a golden age of daring, in the studio and on the street. How did Foxx, who had been through mod and hippie and had an arty sensibility, feel during punk?

“I loved The Damned, I went to see them doing New Rose. I saw the Sex Pistols at the 100 Club, and The Clash – I thought they were great,” he reminisces. “I remember seeing Siouxsie, and [Soo] Catwoman – people who got the image right. [Malcolm] McLaren, the Fagin of the piece, was always skulking about, and Sid [Vicious]. It was really good fun.”

How would he compare and contrast the convulsions of ’76/’77 with the revolution of a decade earlier?

“It was the same, but in the opposite way – ’67 was creative and inclusive, whereas the Pistols were exclusive and violent in intention,” he replies. “I knew what McLaren was up to – I knew about situationism. That’s why I formed the band.”

Foxx had an alien allure that chimed more with the next wave of artists: the likes of Gary Numan, Phil Oakey of The Human League, David Sylvian of Japan and the rest. He insists he got on well with the punks, particularly Rat Scabies and Mick Jones, but it was more the press who had an issue with him – having emerged during punk, he was regarded with suspicion by a media intent on lionising the authentic voice of the street.

With their synths and violins, Ultravox! hardly fit the three-chord mould. They arrived either too early or too late: they would have been at home alongside Bowie and Roxy three years earlier, or they should have come along two years later, when they would have assumed a comfortable position beside Magazine, Simple Minds, Joy Division et al: the experimental post‑punk wing. “New wave before the new wave hit,” as Foxx puts it.

After two 1977 albums – the debut and Ha!-Ha!-Ha!, the latter featuring Hiroshima Mon Amour, of which Foxx says, “I think we made the first electronic moves” – Ultravox lost an exclamation mark but gained a Krautrock producer, Conny Plank, for their third album, 1978’s Systems Of Romance.

But despite a successful US tour and a growing following (which included a young Gary Numan), Foxx was already getting itchy feet. The likes of Robert Rental, Daniel Miller and Thomas Leer were discovering the merits of budget synths and “rock was becoming something else”.

An article in Sounds about the new wave of electronic music suggested the future would be synthesised, so Foxx quit the band to become, as Robert Fripp would have it, “a small, mobile, intelligent unit”: a solo artist. It was a progressive step prompted by the democratisation of technology.

“I was convinced the next stage was to do with cheap mono synths and a cheap tape recorder,” Foxx reflects. “There was something to explore that was completely new.”

Having encouraged Numan to make the moves he did, it was seeing the Tubeway Army star on Top Of The Pops that galvanised Foxx. By 1980, he had released a series of singles – Underpass, No One Driving, Burning Car – and a classic album, Metamatic, that created a new paradigm: icy, electronic pop music imbued with societal dread and Cold War panic, expressed with the cool dispassion of a man who had previously declared that he “intended to live without emotions” (an ambition captured on Ultravox!’s I Want To Be A Machine).

Foxx remembers recording Metamatic and the grim dog days of the late 70s, an era of strikes, dissent and nuclear terror. Talk about fear in the Western world.

“I’d be walking across Leicester Square [to the studio] with all the rubbish piled high, and three hours of electricity a day. You couldn’t help but be affected by it. The Cold War was a constant threat, of the whole world going up in flames at any moment. That’s why a lot of music at that point is ferociously angry or frustrated or cold… They were all ways to combat that threat of immolation.”

Foxx cut a stark, dark figure at the height of new romantic, and even though he had much in common, tech‑wise, with Soft Cell, OMD, The Human League and Depeche Mode, he felt like an outsider. He issued three further solo albums – 1981’s The Garden; 1983’s The Golden Section, which he regarded as psychedelic; and 1985’s In Mysterious Ways, before bowing out for several years, eschewing music for design (the book cover of Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh was one of his) and teaching.

He made a tentative return to the fray in 1990, inspired by the underground house and acid music scenes in Detroit and London, and then in 1997 he began recording again in earnest.

Since then, he has recorded dozens of singles, EPs and albums in a variety of styles, and worked with a slew of artists, from avant-garde composer Harold Budd and Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie to relative unknowns such as Benge (as John Foxx And The Maths), The Belbury Circle and Mancunian ex-raver Louis Gordon. So far in 2023, he has released five albums, via Bandcamp.

His work ranges from haunting, eerie pop and oceanic ambient (leitmotifs include memory and atmosphere) to crashing techno. From noise to silence and back again.

“I need both,” he says. “I love fierce music, but some days you want to hear something with a bit of space, that can make the room luminous with quiet.”

Has part of the secret of his survival – to the point where he’s more highly regarded today than ever – been keeping his distance from it all, not immersing himself in the lifestyle, being an outsider?

“It is a bit like that,” he agrees. “I never feel totally part of things. I love new things and new developments and the people who make them, and I always want to get involved. But I do keep a slight distance. I approach things in a sort of anthropological way. I’m there with my butterfly net and shorts in the jungle, looking for new species.”

This interview was first published in Prog issue 82, 2017. John Foxx's most recent releases are available via his Bandcamp page. His Facebook page has the most up-to-date news of his many recent releases.