Blockchain activists are mounting an insurrection in the traditional art market.

On March 3, an anonymous group calling themselves “art and NFT enthusiasts” set alight a US$95,000 Banksy original print live on social media and put up its non-fungible token (NFT) – a digitised, one-of-a-kind version of the print – for investors to bid on. After a five-day bidding war, it sold for 228.69 Ether, a cryptocurrency, on the trading platform OpenSea, an amount equivalent to about US$380,000.

Earlier in the week, the singer known as Grimes made US$6 million in 20 minutes by selling her digital artworks, also sold as NFTs, in an online auction.

While the former was most likely a stunt – Morons (White) (2006) by British graffiti artist Banksy was never intended to be destroyed and resurrected in the virtual world 15 years later – the latter shows how NFTs are becoming a widely accepted and legitimate means of authentication for digital (or digitised) art and its ownership.

Bizarre sculptures of autistic, non-verbal artist ‘speak for themselves’

NFTs, pronounced “Nifties”, are a means of stamping any digital asset as a one-of-a-kind “original”. They carry a unique ID tag - based on the digital ledger infrastructure, or blockchain, commonly associated with cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin - that is traceable back to the asset’s original creator. This ID serves as a digital representation of that creator’s “signature” authenticating the asset as the original version.

While there are no such originals for digital works without an NFT - only an endless supply of identical copies - just one or a few versions of an NFT-based work are “minted” on the blockchain. This scarcity introduces value and exclusivity to the digital art world, with NFTs able to be owned, collected and traded just like other physical assets such as hand-painted works.

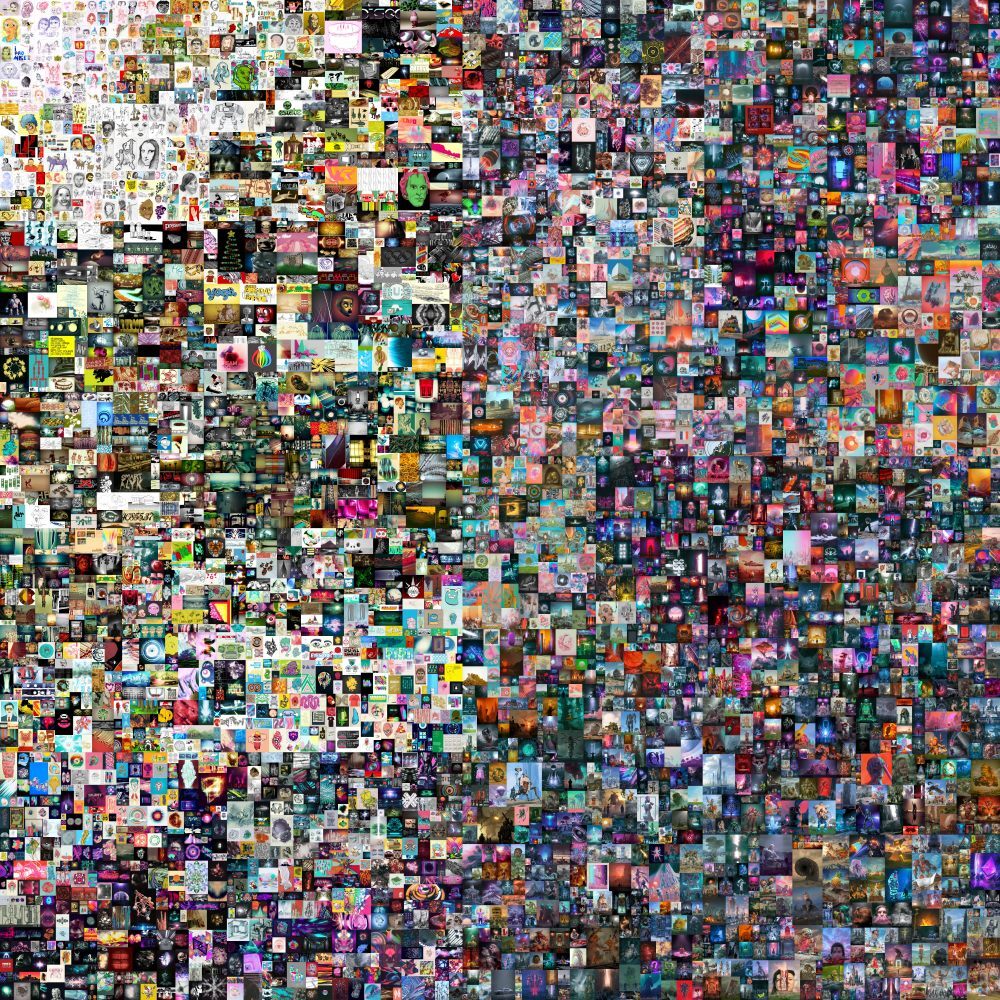

In February, the 255-year-old auction house Christie’s began a two-week auction for Everydays: The First 5,000 Days by Mike Winkelmann, a graphic designer more commonly known as Beeple. According to Christie’s, the work is the first “purely digital” NFT ever to be sold by a traditional auction house.

The starting price was a modest US$100. Within hours, the bidding had shot past the US$1.8 million mark, and sat at US$8.3 million on March 9. The auction is due to finish on March 11.

NFTs existed long before making their entrance in the art world. One of the earliest NFT collecting crazes was for CryptoKitties, a kind of digital pet first released in 2017. Now, people are paying millions of dollars for anything from video game avatars and GIFs and to individual tweets by celebrities. (Twitter co-founder and CEO Jack Dorsey recently put up his first tweet for auction as an NFT. The highest bid for the tweet, which reads “just setting up my twtrr”, stood at US$2.5 million on March 9.)

Winkelmann has long stood at the forefront of NFT-based digital art. He set a record on the specialist trading platform Nifty Gateway last December when a series of his pieces sold for a total of over US$3.5 million. That was shattered in the days leading up to the Christie’s auction when another of his works went for US$6.6 million, making it the most expensive digital piece ever auctioned, according to Nifty Gateway.

Everydays: The First 5,000 Days is a collage of 5,000 digital images that Winkelmann made daily over 13 years to practise and hone his drawing skills on his computer. By the time he completed the final picture on January 7, he had achieved a meteoric and unlikely rise to internet fame. The collection captures his growth as a designer and artist, set on the backdrop of larger sociopolitical trends and the rapid development of the digital tools artists have at their fingertips.

“It really is a diary of technology, my life and the world over these last 13 years,” he says.

Winkelmann’s cartoonish, sometimes monstrous, portrayals of well-known cultural figures and symbols have proved a provocative hit with young people, earning him 1.9 million Instagram followers and design gigs with brands such as Nike and Louis Vuitton.

Collectors in Asia and those of Asian descent were among the early buyers of Beeple NFTs. A collector calling himself MetaKovan, rumoured to live in Singapore, bought all but one of the 21 pieces Winkelmann sold during an auction on Nifty Gateway last December.

The mysterious collector already owned a large collection of NFTs, including a section of a racetrack and a digital racing car for F1 Delta Time - an online motorsports blockchain game on the Ethereum platform - for the record-setting prices of US$223,000 and US$113,000, respectively.

Tim Kang is another prominent collector with a history of buying Winkelmann’s works. Born to South Korean immigrants and based in Los Angeles, the banker turned cryptocurrency enthusiast outbid MetaKovan for a Winkelmann piece at the December auction, spending US$777,777.

In Hong Kong, cryptocurrency investor and art collector Jehan Chu is jumping in on the bidding for Everydays. The founder of Hong Kong-based Kenetic Capital – which invests in a number of companies bringing NFTs to other industries, such as event ticketing – Chu believes the Christie’s auction will mark the technology’s entrance into the mainstream.

If a traditional fine art collector ends up buying the piece, it will represent “the ultimate validation of NFTs as an art form”, Chu says.

“This is not just a referendum on Beeple’s work. It is a referendum on an entirely new medium for the global art market. Beeple is like the Tiger Woods of NFTs. He is the pioneer, the one who is changing the game,” Chu says.

Some in the art world do see NFTs as more than a temporary fad, with the technology able to resolve long-standing problems over authentication.

“We’ve seen the problems with regard to artists’ foundations being unable to authenticate their own works,” said Robert Norton, founder and CEO of the blockchain art firm Verisart, at a 2018 Art Basel panel. The transparency of the blockchain will prove a lasting way to resolve these problems going forward, Norton added, easily separating valid works from knock-offs.

Yet some people say that any speculative investment in art, which NFTs seem to fuel, is simply a way of making money and has little to do with the art itself. Others believe it only brings the most conservative traditions of the art world to the digital realm.

“I guess NFTs are kind of interesting, but they’re certainly not revolutionary,” says Blake Gopnik, an American art critic and the author of Warhol, a biography of pop artist Andy Warhol. “It’s not shaking anything up, but completely capitulating to the worst aspects of the traditional art world. The notion that there is something magical in an original piece of art signed by the master’s hand that distinguishes itself from copies is extremely conservative and old-fashioned.”

Debates about the value of authenticity and attribution are not new to the art world, and Warhol mocked the notion decades ago. In 1966, he placed a classified ad in The Village Voice magazine asking people to bring him random objects that he would then sign and certify as original authentic “Warhols”.

“Warhol was playing games, making a joke about authenticity and the silliness that a signature and only a signature can distinguish something as modern art,” Gopnik says, jokingly adding that he wouldn’t be surprised if Winkelmann was playing a similarly sophisticated game to mock what he says is the antiquated understanding many in the NFT space have of art.

Noah Davis, a Christie’s specialist in post-war and contemporary art who helped organise the auction, said there “absolutely” was scepticism about Everydays among the more traditional elements of the art-collecting community. The auction house had to reject Winkelmann’s first draft of Everydays for being “a little too challenging for our audience”, he says.

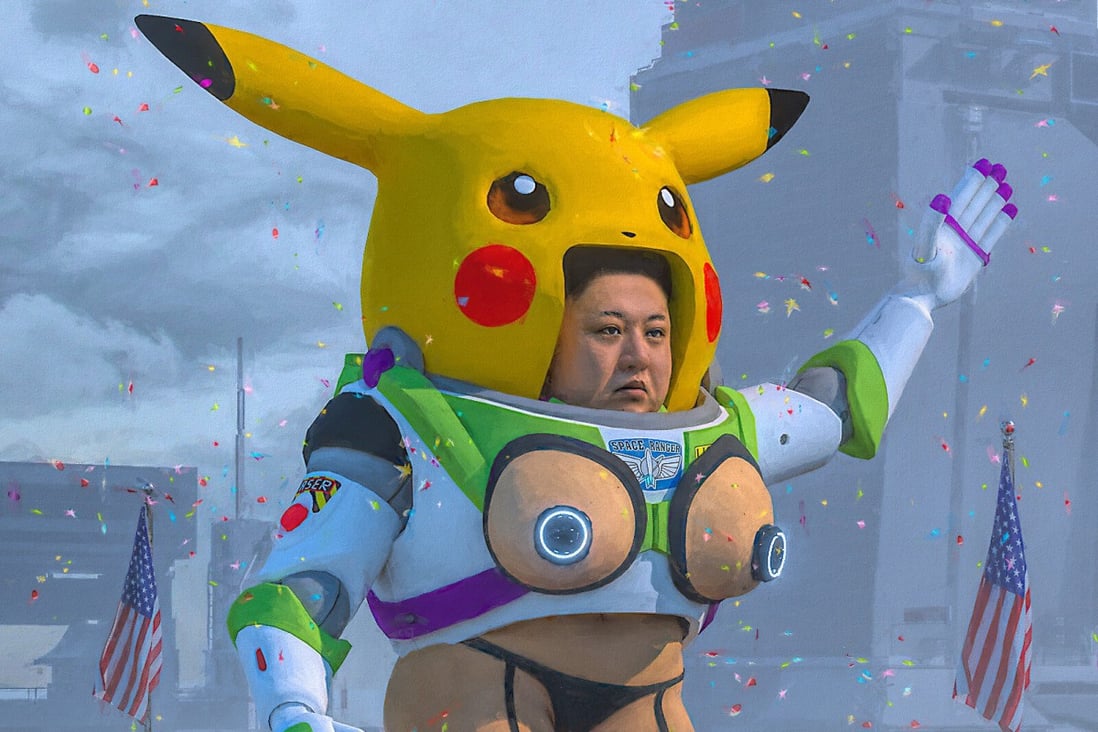

Winkelmann says among his personal favourite images that make up Everydays is a mocking “rebrand” of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un decked out in Pikachu headgear and a piece of Buzz Lightyear’s suit, complete with breasts and long legs covered only by a dainty piece of underwear.

Another features two individuals sitting on a bench, joyously drinking milk from nozzles connected to the artificial breasts of a Buzz Lightyear milk machine hybrid, aptly named Buzz Lightmilk.

He says of Buzz Lightyear’s frequent appearances in his art: “He’s just got this stupid grin on his face … sort of an analogy for ‘super-America’ and capitalist weirdness.”

Even after completing what might be considered his life’s work, Winkelmann says he has “massive room for improvement” and intends to continue creating the daily pieces for the rest of his life.

He says he has never cheated and has conceived, created and posted a new image online every single day for over 13 years now. But he does recall a day two years ago when he was left anxiously stewing over a potential end to his streak.

He was taking an overnight flight to Brazil for a conference, meaning he had to post his completed picture before taking off. About an hour into the flight, which offered no internet service, he suddenly had the thought that perhaps he had forgotten to send out the post.

Mother from 11-year-old viral photo finally found, and how things have changed

“It was just a brutal, brutal eight hours for the rest of that flight,” he recalls. “I was turning aeroplane mode on and off to try and catch a signal miraculously over the middle of the Amazon rainforest, as if there was going to be this magical cell tower that people had built but forgotten about.”

After the plane landed he immediately jumped online. To his relief, he had remembered to post the image. The streak would continue.